1961 Ndola United Nations DC-6 crash on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

On 18 September 1961, a

In September 1961, during the

In September 1961, during the

Following the death of Hammarskjöld, there were three inquiries into the circumstances that led to the crash: the Rhodesian Board of Investigation, the Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry, and the United Nations Commission of Investigation.

(direct link: )

The Rhodesian Board of Investigation looked into the matter between 19 September 1961 and 2 November 1961 under the command of

Following the death of Hammarskjöld, there were three inquiries into the circumstances that led to the crash: the Rhodesian Board of Investigation, the Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry, and the United Nations Commission of Investigation.

(direct link: )

The Rhodesian Board of Investigation looked into the matter between 19 September 1961 and 2 November 1961 under the command of

DC-6

The Douglas DC-6 is a piston-powered airliner and cargo aircraft built by the Douglas Aircraft Company from 1946 to 1958. Originally intended as a military transport near the end of World War II, it was reworked after the war to compete with th ...

passenger aircraft of Transair Sweden

Transair Sweden AB (ICAO: TB) was a Swedish charter airline that operated until 1981.

History

Transair Sweden began as Nordisk Aerotransport AB in 1950 with the purpose of flying newspapers from Stockholm to other locations in Sweden using Air ...

, operating for the United Nations, crashed near Ndola

Ndola is the third largest city in Zambia and third in terms of size and population, with a population of 475,194 (''2010 census provisional''), after the capital, Lusaka, and Kitwe, and the second largest in terms of infrastructure development aft ...

, Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in southern Africa, south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by Amalgamation (politics), amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-West ...

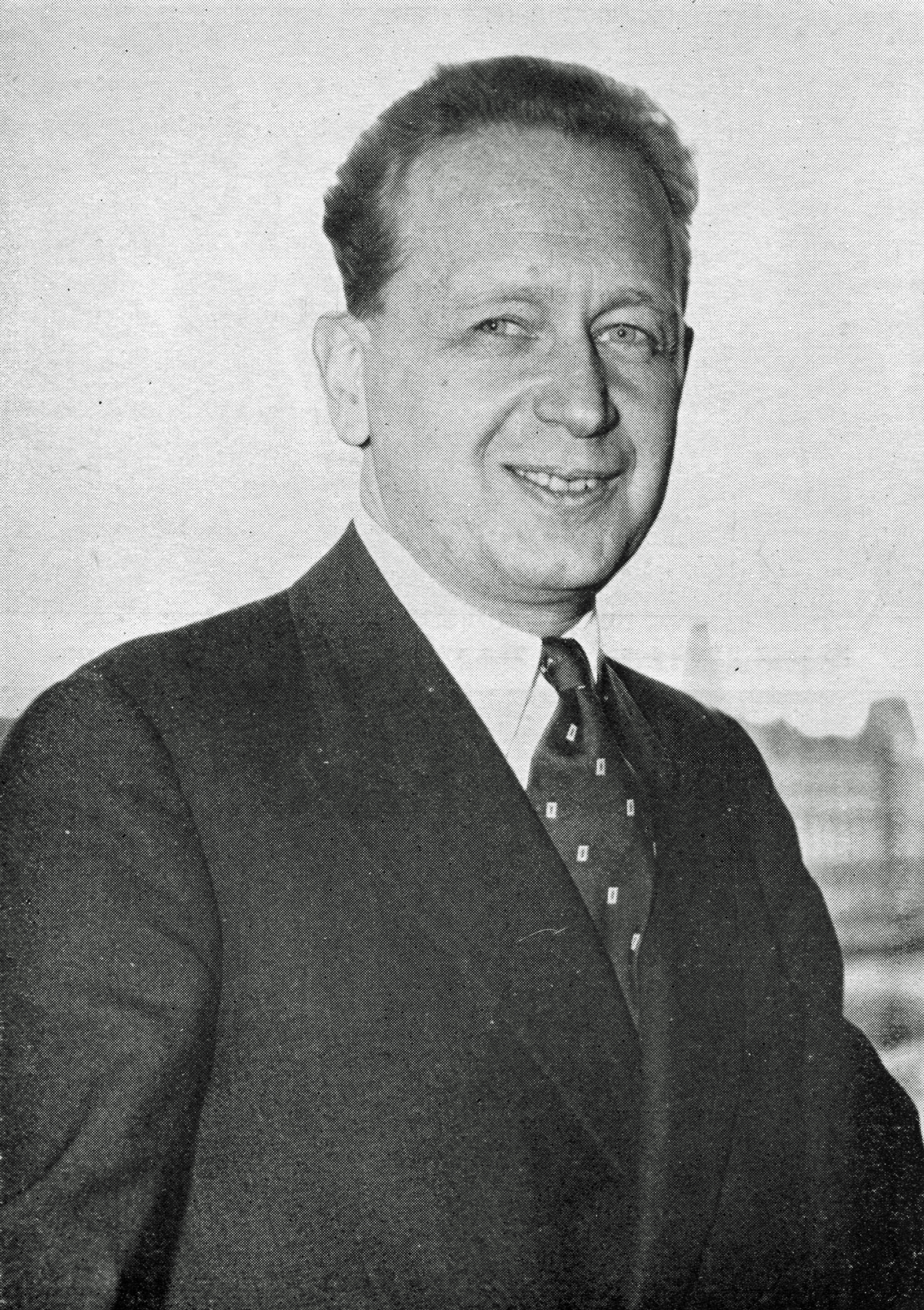

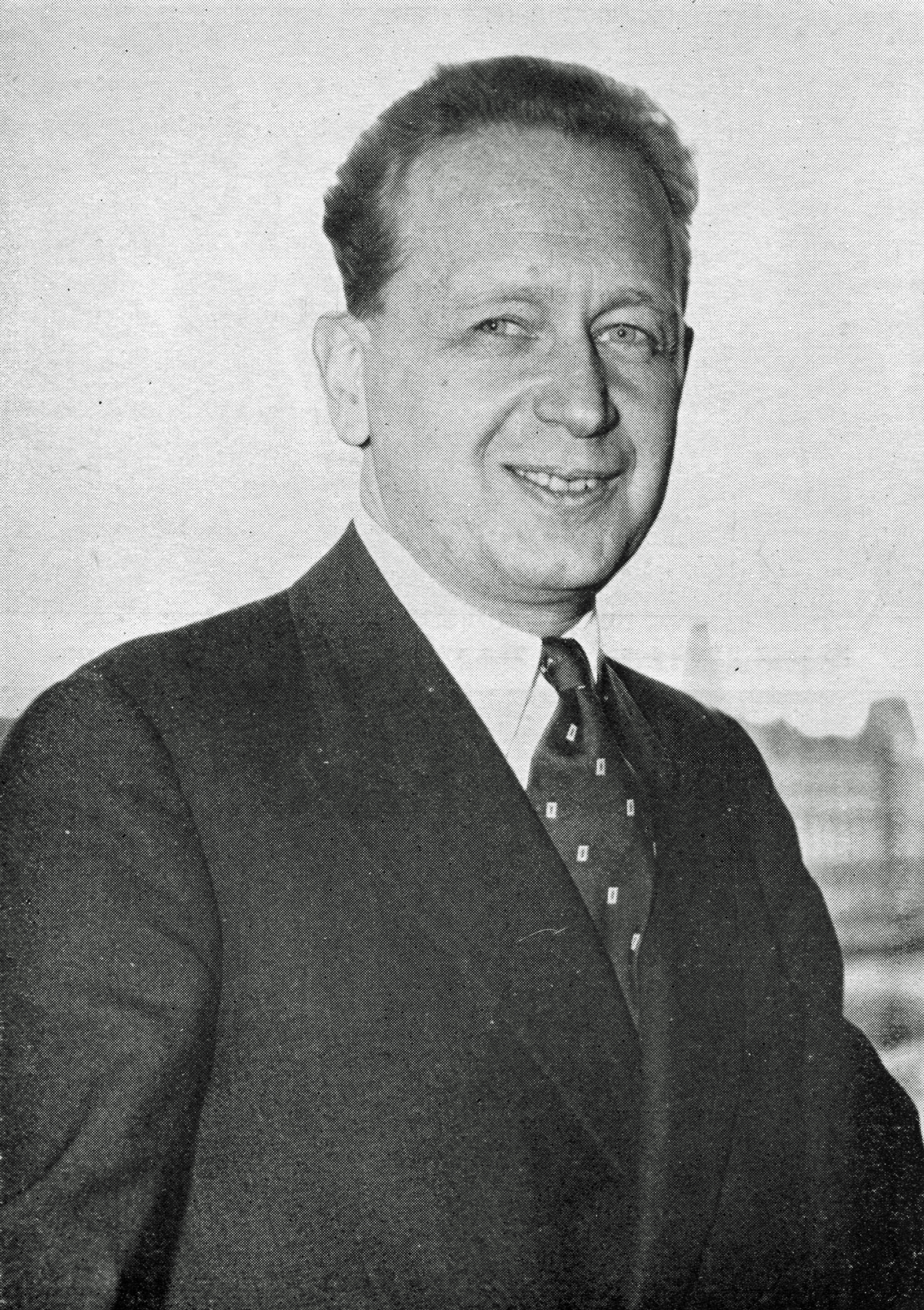

(present-day Zambia). The crash resulted in the deaths of all people onboard including Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld ( , ; 29 July 1905 – 18 September 1961) was a Swedish economist and diplomat who served as the second Secretary-General of the United Nations from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 196 ...

, the second Secretary-General of the United Nations, and 15 others. Hammarskjöld had been ''en route'' to cease-fire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state act ...

negotiations with Moise Tshombe

Moise is a given name and surname, with differing spellings in its French and Romanian origins, both of which originate from the name Moses: Moïse is the French spelling of Moses, while Moise is the Romanian spelling. As a surname, Moisè and Mo ...

during the Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis (french: Crise congolaise, link=no) was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost immediately after ...

. Three official inquiries failed to determine conclusively the cause of the crash, which set off a succession crisis at the United Nations.

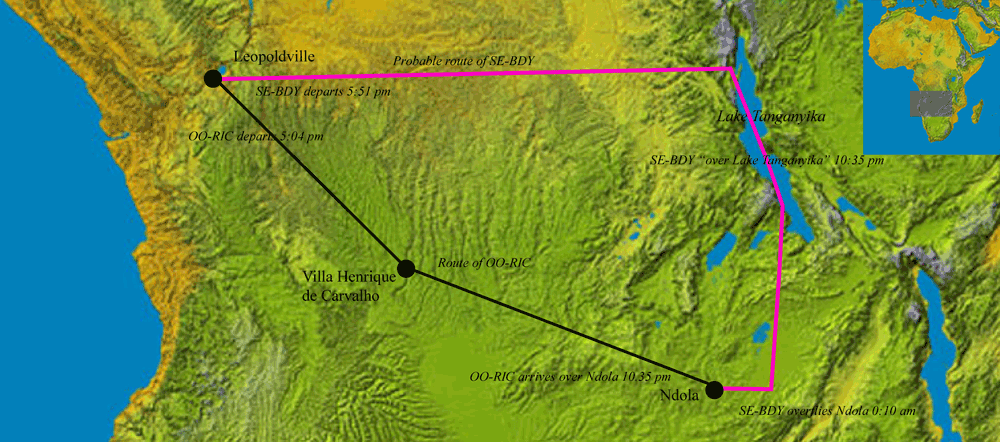

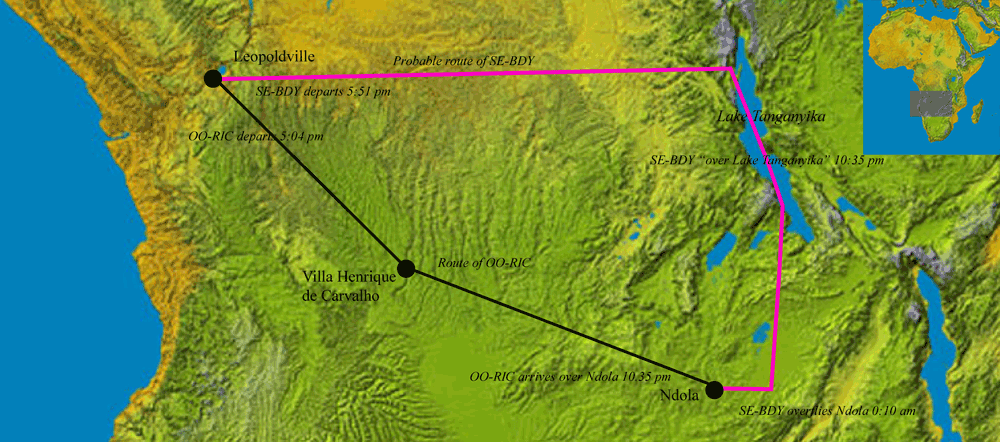

Incident

In September 1961, during the

In September 1961, during the Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis (french: Crise congolaise, link=no) was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost immediately after ...

, Hammarskjöld learned about fighting between "non-combatant" UN forces and Katangese troops of Moise Tshombe

Moise is a given name and surname, with differing spellings in its French and Romanian origins, both of which originate from the name Moses: Moïse is the French spelling of Moses, while Moise is the Romanian spelling. As a surname, Moisè and Mo ...

. On 18 September, Hammarskjöld was en route to negotiate a cease-fire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state act ...

when the aircraft he was flying in crashed near Ndola

Ndola is the third largest city in Zambia and third in terms of size and population, with a population of 475,194 (''2010 census provisional''), after the capital, Lusaka, and Kitwe, and the second largest in terms of infrastructure development aft ...

, Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in southern Africa, south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by Amalgamation (politics), amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-West ...

(now Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most cent ...

). Hammarskjöld and fifteen others perished in the crash. The crash set off a succession crisis at the United Nations, as Hammarskjöld's death required the Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, and ...

to vote on a successor.

Aircraft and crew

The aircraft involved in this accident was aDouglas DC-6B

The Douglas DC-6 is a piston-powered airliner and cargo aircraft built by the Douglas Aircraft Company from 1946 to 1958. Originally intended as a military transport near the end of World War II, it was reworked after the war to compete with ...

, c/n 43559/251, registered in Sweden as SE-BDY, first flown in 1952 and powered by four Pratt & Whitney R-2800

The Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp is an American twin-row, 18-cylinder, air-cooled radial aircraft engine with a displacement of , and is part of the long-lived Wasp family of engines.

The R-2800 saw widespread use in many importan ...

18-cylinder radial piston engines. It was flown by Captain Per Hallonquist (35); First Officer Lars Litton (29); and Flight Engineer Nils Goran Wilhelmsson.

UN special report

A special report issued by the United Nations following the crash stated that a bright flash in the sky was seen at approximately 01:00. According to the UN special report, it was this information that resulted in the initiation of search and rescue operations. Initial indications that the crash might not have been an accident led to multiple official inquiries and persistent speculation that the secretary-general was assassinated.Official inquiry

Following the death of Hammarskjöld, there were three inquiries into the circumstances that led to the crash: the Rhodesian Board of Investigation, the Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry, and the United Nations Commission of Investigation.

(direct link: )

The Rhodesian Board of Investigation looked into the matter between 19 September 1961 and 2 November 1961 under the command of

Following the death of Hammarskjöld, there were three inquiries into the circumstances that led to the crash: the Rhodesian Board of Investigation, the Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry, and the United Nations Commission of Investigation.

(direct link: )

The Rhodesian Board of Investigation looked into the matter between 19 September 1961 and 2 November 1961 under the command of Lt. Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the army, armies, most Marine (armed services), marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use t ...

M.C.B. Barber. The Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry, under the chairmanship of Sir John Clayden, held hearings from 16–29 January 1962 without United Nations oversight. The subsequent United Nations Commission of Investigation held a series of hearings in 1962 and in part depended upon the testimony from the previous Rhodesian inquiries. Five "eminent persons" were assigned by the new secretary-general to the UN Commission. The members of the commission unanimously elected Nepalese diplomat Rishikesh Shaha

Rishikesh Shah (May 16, 1925 – November 13, 2002) was a Nepalese writer, politician and human rights activist.

The three official inquiries failed to determine conclusively the cause of the crash that led to the death of Hammarskjöld. The Rhodesian Board of Investigation sent 180 men to search a six-square-kilometer area of the last sector of the aircraft's flight path, looking for evidence as to the cause of the crash. No evidence of a bomb,

The

The

Dag Hammarskjöld archives

o

UN Archives website

and ttp://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/september/18/newsid_3790000/3790079.stm BBC {{DEFAULTSORT:Ndola United Nations DC-6 crash Aviation accidents and incidents in Zambia Congo Crisis Conspiracy theories involving aviation incidents Aviation accidents and incidents in 1961 Accidents and incidents involving the Douglas DC-6 Death conspiracy theories September 1961 events in Africa Aviation accident investigations with disputed causes

surface-to-air missile

A surface-to-air missile (SAM), also known as a ground-to-air missile (GTAM) or surface-to-air guided weapon (SAGW), is a missile designed to be launched from the ground to destroy aircraft or other missiles. It is one type of anti-aircraft syst ...

, or hijacking was found. The official report stated that two of the dead Swedish bodyguards had suffered multiple bullet wounds. Medical examination, performed by the initial Rhodesian Board of Investigation and reported in the UN official report, indicated that the wounds were superficial, and that the bullets showed no signs of rifling

In firearms, rifling is machining helical grooves into the internal (bore) surface of a gun's barrel for the purpose of exerting torque and thus imparting a spin to a projectile around its longitudinal axis during shooting to stabilize the pro ...

. They concluded that cartridges had exploded in the fire in proximity to the bodyguards. No evidence of foul play was found in the wreckage of the aircraft. The Rhodesian Board concluded that the pilot flew too low and struck trees, thereby bringing the aircraft to the ground.

Previous accounts of a bright flash in the sky were dismissed as occurring too late in the evening to have caused the crash. The UN report speculated that these flashes may have been caused by secondary explosions after the crash. Sergeant Harold Julien, who initially survived the crash but died five days later, indicated that there was a series of explosions that preceded the crash. The official inquiry found that the statements of witnesses who talked with Julien before he died in hospital five days after the crash were inconsistent.

The report states that there were numerous delays that violated established search and rescue procedures. There were three separate delays: the first delayed the initial alarm of a possible plane in trouble; the second delayed the "distress" alarm, which indicates that communications with surrounding airports indicate that a missing plane has not landed elsewhere; the third delayed the eventual search and rescue operation and the discovery of the plane wreckage, just kilometres/miles away. The medical examiner's report was inconclusive; one report said that Hammarskjöld had died on impact; another stated that Hammarskjöld might have survived had rescue operations not been delayed. The report also said that the chances of Sgt. Julien surviving the crash would have been "infinitely" better if the rescue operations had been hastened.

On 16 March 2015, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

Ban Ki-moon (; ; born 13 June 1944) is a South Korean politician and diplomat who served as the eighth secretary-general of the United Nations between 2007 and 2016. Prior to his appointment as secretary-general, Ban was his country's Minister ...

appointed members to an independent panel of experts to examine new information related to the tragedy. The three-member panel was led by Mohamed Chande Othman

Mohamed Chande Othman (born 1 January 1952) is a Tanzanian lawyer and a former Chief Justice of Tanzania.

Internationally he is highly respected for his deep understanding of political, legal and other dimensions relating to International Human ...

, the Chief Justice of Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

. The other two members were Kerryn Macaulay (Australia's representative to ICAO) and Henrik Larsen (a ballistics expert from the Danish National Police). The report was handed over to the secretary-general on 12 June 2015. The panel's 99-page report, released 6 July 2015, assigned "moderate" value to nine new eyewitness accounts and transcripts of radio transmissions. Those accounts suggested that Hammarskjöld's plane was already on fire as it landed and that other jet aircraft and intelligence agents were nearby.

Alternative theories

Despite the multiple official inquiries that failed to find evidence of assassination or other forms of foul play, several individuals have continued to advance a theory of the crash being deliberately caused by hostile interests. At the time of Hammarskjöld's death, theCentral Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

and other Western agencies were actively involved in the political situation in the Congo, which culminated in Belgian and US support for the secession of Katanga and the assassination of former prime minister Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba (; 2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic of the Congo) from June u ...

. The Belgian government

The Federal Government of Belgium ( nl, Federale regering, french: Gouvernement fédéral, german: Föderalregierung) exercises executive power in the Kingdom of Belgium. It consists of ministers and secretary of state ("junior", or deputy-mini ...

had a vested interest in maintaining their control over much of the country's copper industry during the Congolese transition from colonial rule to independence. Concerns about the nationalisation of the copper industry could have provided a financial incentive to remove either Lumumba or Hammarskjöld.

The official inquiry has come under scrutiny and criticism from historians, who point to a number of conclusions made which they claim were done to steer focus away from the assassination angle. The official report dismissed a number of pieces of evidence that would have supported the view that Hammarskjöld was assassinated. Some of these dismissals have been criticized, such as the conclusion that bullet wounds could have been caused by bullets exploding in a fire. Expert tests have questioned this conclusion, arguing that exploding bullets could not break the surface of the skin. Major C. F. Westell, a ballistics authority, said, "I can certainly describe as sheer nonsense the statement that cartridges of machine guns or pistols detonated in a fire can penetrate a human body." He based his statement on a large scale experiment that had been done to determine if military fire brigades would be in danger working near munitions depots. Other experts conducted and filmed tests showing that bullets heated to the point of explosion did not achieve sufficient velocity to penetrate their box container.

On 19 August 1998, Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (7 October 193126 December 2021) was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. He was Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then Archbishop ...

, chairman of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission

A truth commission, also known as a truth and reconciliation commission or truth and justice commission, is an official body tasked with discovering and revealing past wrongdoing by a government (or, depending on the circumstances, non-state act ...

(TRC), stated that recently uncovered letters had implicated MI5

The Security Service, also known as MI5 ( Military Intelligence, Section 5), is the United Kingdom's domestic counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), Go ...

, the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

, and then South African intelligence services in the crash. One TRC letter said that a bomb in the aircraft's wheel bay was set to detonate when the wheels came down for a landing. Tutu said that they were unable to investigate the truth of the letters or the allegations that South African or Western intelligence agencies played a role in the crash. The British Foreign Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom. Equivalent to other countries' ministries of foreign affairs, it was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreign ...

suggested that they may have been created as Soviet misinformation

Misinformation is incorrect or misleading information. It differs from disinformation, which is ''deliberately'' deceptive. Rumors are information not attributed to any particular source, and so are unreliable and often unverified, but can turn ou ...

or disinformation

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but is not deliberate.

The English word ''disinformation'' comes from the application of the L ...

.

On 29 July 2005, Norwegian Army Major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Bjørn Egge

Bjørn Egge CBE (19 August 1918 – 25 July 2007) was a Major General of the Norwegian Army and President of the Norwegian Red Cross (1981–1987). He served as deputy head of the NATO Defence College (1976–1980).

Egge was a soldier during th ...

gave an interview to the newspaper ''Aftenposten

( in the masthead; ; Norwegian for "The Evening Post") is Norway's largest printed newspaper by circulation. It is based in Oslo. It sold 211,769 copies in 2015 (172,029 printed copies according to University of Bergen) and estimated 1.2 million ...

'' on the events surrounding Hammarskjöld's death. According to Egge, who had been the first UN officer to see the body, Hammarskjöld had a hole in his forehead, and this hole was subsequently airbrush

An airbrush is a small, air-operated tool that atomizes and sprays various media, most often paint but also ink and dye, and foundation. Spray painting developed from the airbrush and is considered to employ a type of airbrush.

History

U ...

ed from photos taken of the body. It appeared to Egge that Hammarskjöld had been thrown from the plane, and grass and leaves in his hands might indicate that he survived the crash – and that he had tried to scramble away from the wreckage. Egge did not officially claim that the wound was a gunshot wound.

In his speech to the 64th session of the UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

on 23 September 2009, Colonel Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spelling ...

called upon the Libyan president of UNGA, Ali Treki

Ali Abdussalam Treki ( ar, علي عبد السلام التريكي; 10 October 1937 – 19 October 2015) was a Libyan diplomat in Muammar Gaddafi's regime. Treki served as one of Libya's top diplomats beginning in the 1970s and ending wit ...

, to institute a UN investigation into the deaths of Congolese prime minister, Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba (; 2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic of the Congo) from June u ...

, who was overthrown in 1960 and murdered the following year, and of Hammarskjöld in 1961.

According to a dozen witnesses interviewed by Swedish aid worker Göran Björkdahl in the 2000s, Hammarskjöld's plane was shot down by another aircraft. Björkdahl also reviewed previously unavailable archive documents and internal UN communications. He believes that there was an intentional shoot down for the benefit of mining companies like Union Minière. A US intelligence officer who was stationed at an electronic surveillance station in Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

stated that he heard a cockpit recording from Ndola

Ndola is the third largest city in Zambia and third in terms of size and population, with a population of 475,194 (''2010 census provisional''), after the capital, Lusaka, and Kitwe, and the second largest in terms of infrastructure development aft ...

. In the cockpit recording a pilot talks of closing in on the DC-6 in which Hammarskjöld was traveling, guns are heard firing, and then the words "I've hit it".

In 2011, the study by Susan Williams ''Who Killed Hammarskjold?'', a University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

scholar of decolonisation in Africa outlined several serious doubts about the accidental character of the plane crash in 1961. It led to the formation of independent, unofficial commission of inquiry in 2012 to provide an opinion on whether there was new evidence that would justify the UN re-opening its 1962 inquiry – the commission was headed by the British jurist Stephen Sedley

Sir Stephen John Sedley (born 9 October 1939) is a British lawyer. He worked as a judge of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales from 1999 to 2011 and was a visiting professor at the University of Oxford from 2011 to 2015.

Early life and ed ...

. The Sedley commission's report was presented on 9 September 2013, at the Peace Palace

, native_name_lang =

, logo =

, logo_size =

, logo_alt =

, logo_caption =

, image = La haye palais paix jardin face.JPG

, image_size =

, image_alt =

, image_caption = The Peace Palace, The Hague

, map_type =

, map_alt =

, m ...

in The Hague. It recommended that the UN re-open its inquiry "pursuant to General Assembly resolution 1759 (XVII) of 26 October 1962". Its findings formed the basis of the constitution of a panel of experts, and in March 2015 the appointment of Eminent Person Mohamed Chande Othman

Mohamed Chande Othman (born 1 January 1952) is a Tanzanian lawyer and a former Chief Justice of Tanzania.

Internationally he is highly respected for his deep understanding of political, legal and other dimensions relating to International Human ...

at the UN to support the ongoing ''Hammarskjöld Commission''.

In April 2014, ''the Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' published evidence implicating Jan van Risseghem, a military pilot who served with the RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

during World War II, later with the Belgian Air Force

The Belgian Air Component ( nl, Luchtcomponent, french: Composante air) is the air arm of the Belgian Armed Forces, and until January 2002 it was officially known as the Belgian Air Force ( nl, Belgische Luchtmacht; french: Force aérienne belg ...

, and who became known as the pilot of Moise Tshombe

Moise is a given name and surname, with differing spellings in its French and Romanian origins, both of which originate from the name Moses: Moïse is the French spelling of Moses, while Moise is the Romanian spelling. As a surname, Moisè and Mo ...

in Katanga. The article claims that an American NSA

The National Security Agency (NSA) is a national-level intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collectio ...

employee, former naval pilot Commander Charles Southall, working at the NSA listening station in Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

in 1961 shortly after midnight on the night of the crash, heard an intercept of a pilot's commentary in the air over Ndola, away. Southall recalled the pilot saying: "I see a transport plane coming low. All the lights are on. I'm going down to make a run on it. Yes, it is the Transair DC-6. It's the plane," adding that his voice was "cool and professional". Then he heard the sound of gunfire and the pilot exclaiming: "I've hit it. There are flames! It's going down. It's crashing!" Based on aircraft registration and availability with the Katangese Air Force

The Katangese Air Force (french: Force aérienne katangaise, or FAK) or Katangese Military Aviation (french: Aviation militaire Katangaise, or Avikat) was a short lived air force of the State of Katanga, established in 1960 under the command of Jan ...

, registration KAT-93, a Fouga CM.170 Magister would be the most likely aircraft used and the website Belgian Wings claims that van Risseghem piloted the Magisters for the KAF in 1961. A further article was published by ''The Guardian'' in January 2019, repeating the allegations against van Risseghem and citing further evidence uncovered by the makers of the documentary ''Cold Case Hammarskjöld

''Cold Case Hammarskjöld'' is a 2019 documentary film by Danish film maker Mads Brügger. It depicts the death of Dag Hammarskjöld in the 1961 Ndola United Nations DC-6 crash and proposes a theory that a white supremacist organization attempted ...

'', including refutations of his alibi that he was not flying at the time of the crash.

In December 2018, the German freelance historian Torben Gülstorff published an article in the ''Lobster

Lobsters are a family (biology), family (Nephropidae, Synonym (taxonomy), synonym Homaridae) of marine crustaceans. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on the sea floor. Three of their five pairs of legs ...

magazine'', arguing that a German Dornier DO-28A may have been used for the attack on Hammarskjöld's DC-6. The plane was delivered to Katanga by end of August 1961 and would have been technically capable of accomplishing such an assault.

Memorial

The

The Dag Hammarskjöld Crash Site Memorial

The Dag Hammarskjöld Memorial Crash Site marks the place of the plane crash in which Dag Hammarskjöld, the second and then-sitting Secretary-General of the United Nations was killed on 17 September 1961, while on a mission to the Léopoldville ...

is under consideration for inclusion as a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

World Heritage Site. A press release issued by the Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo stated that, "... in order to pay a tribute to this great man, now vanished from the scene, and to his colleagues, all of whom have fallen victim to the shameless intrigues of the great financial Powers of the West... the Government has decided to proclaim Tuesday, 19 September 1961, a day of national mourning."

In media

* The accident and subsequent investigation were featured in the fifteenth season and fifth episode of the documentary series ''Mayday

Mayday is an emergency procedure word used internationally as a distress signal in voice-procedure radio communications.

It is used to signal a life-threatening emergency primarily by aviators and mariners, but in some countries local organiza ...

'' (also known as ''Air Crash Investigation'') titled "Deadly Mission", first broadcast in February 2016.

* In the 2016 film '' The Siege of Jadotville'', Hammarskjöld's plane is intercepted by an F-4 Phantom II

The McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II is an American tandem two-seat, twin-engine, all-weather, long-range supersonic jet interceptor and fighter-bomber originally developed by McDonnell Aircraft for the United States Navy.Swanborough and Bow ...

aircraft, and it is implied that Katangese Prime Minister Moise Tshombe ordered it done, however the film ultimately leaves it ambiguous as Hammarskjöld's plane is never shown actually being shot down, only implied. The film is incorrect, however, in depicting the plane crash as taking place during the six-day attack by Katangese forces against Irish Army

The Irish Army, known simply as the Army ( ga, an tArm), is the land component of the Defence Forces of Ireland.The Defence Forces are made up of the Permanent Defence Forces – the standing branches – and the Reserve Defence Forces. The Ar ...

peacekeepers led by Commandant Pat Quinlan. In reality, Hammarskjöld died the day after the besieged

Besieged may refer to:

* the state of being under siege

* ''Besieged'' (film), a 1998 film by Bernardo Bertolucci

{{disambiguation ...

Irish contingent had surrendered.

* The 2019 film ''Cold Case Hammarskjöld

''Cold Case Hammarskjöld'' is a 2019 documentary film by Danish film maker Mads Brügger. It depicts the death of Dag Hammarskjöld in the 1961 Ndola United Nations DC-6 crash and proposes a theory that a white supremacist organization attempted ...

'' details and dramatizes the investigation into Hammarskjöld's alleged assassination by Danish film director Mads Brügger

Mads Brügger (; born 24 June 1972) is a Danish filmmaker and TV host.

Career Film

Brügger's first two projects, the documentary series '' Danes for Bush'' and the feature ''The Red Chapel'', filmed in the United States and North Korea, respec ...

and Swedish private investigator Göran Björkdahl. The film concludes that Hammarskjöld's plane was shot down by a Belgian mercenary, probably acting as part of a plot with involvement from the CIA, MI6, and a mysterious South African white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other Race (human classification), races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any Power (social and polit ...

paramilitary organization, SAIMR.

Notes

References

External links

Dag Hammarskjöld archives

o

UN Archives website

and ttp://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/september/18/newsid_3790000/3790079.stm BBC {{DEFAULTSORT:Ndola United Nations DC-6 crash Aviation accidents and incidents in Zambia Congo Crisis Conspiracy theories involving aviation incidents Aviation accidents and incidents in 1961 Accidents and incidents involving the Douglas DC-6 Death conspiracy theories September 1961 events in Africa Aviation accident investigations with disputed causes