1500 Tons-class Submarine (1931) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

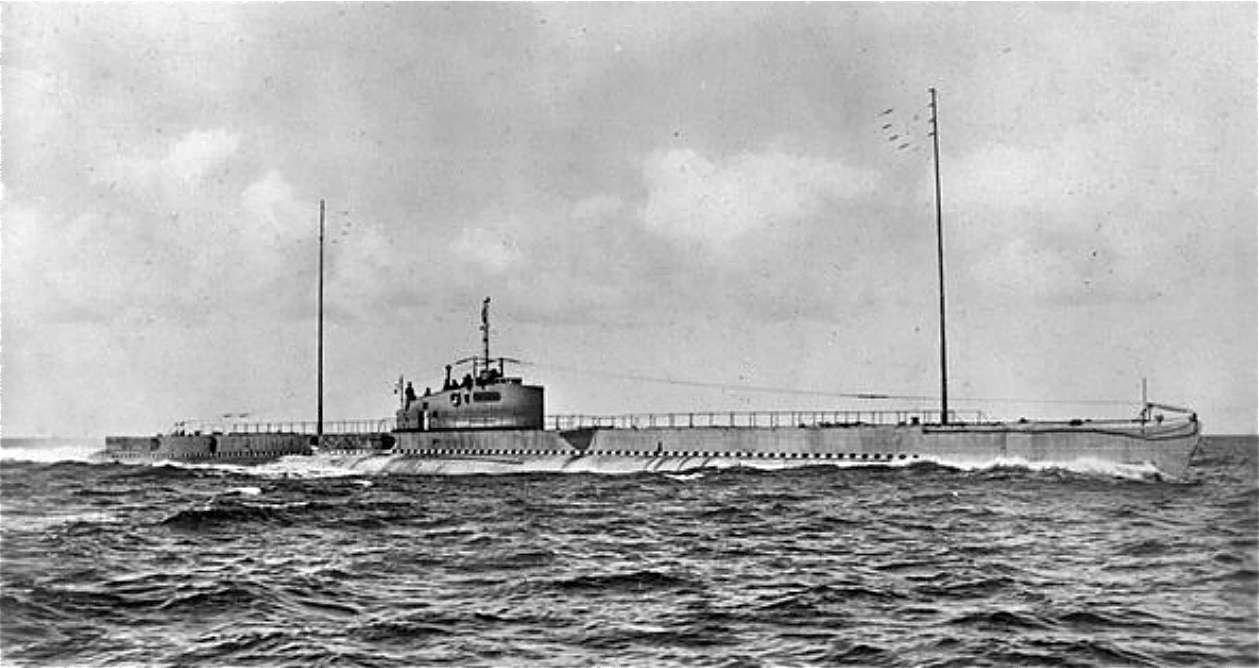

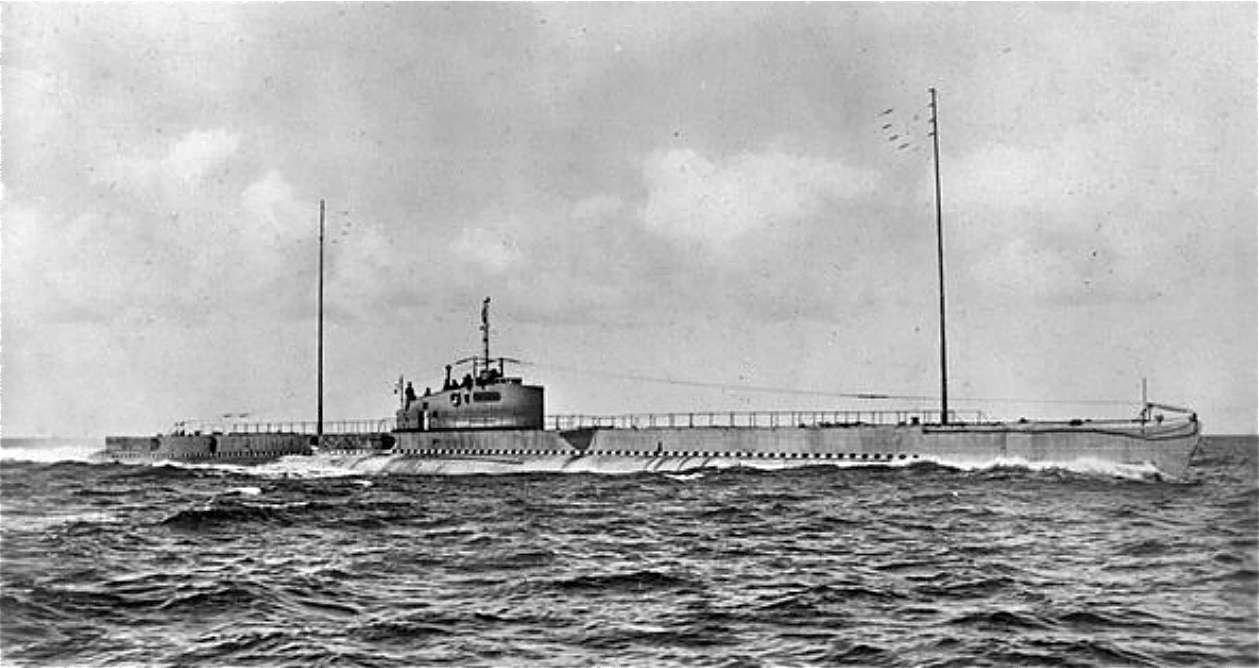

The ''Redoutable''-class submarines were a group of 31 submarines built between 1924 and 1937 for the

The

The

The large construction program made it necessary to contract work out to private shipyards, such as those at

The large construction program made it necessary to contract work out to private shipyards, such as those at

At the beginning of Second World War, the ''Pascal''-type vessels were divided between the First Navy Squadron at

At the beginning of Second World War, the ''Pascal''-type vessels were divided between the First Navy Squadron at

The conditions of the armistice envisaged the return of French naval vessels to their home ports to be disarmed; however, the British attack on Mers-el-Kébir on 3 July convinced the Germans to cancel this plan. The French lost two ''Redoutable''-class submarines during the

The conditions of the armistice envisaged the return of French naval vessels to their home ports to be disarmed; however, the British attack on Mers-el-Kébir on 3 July convinced the Germans to cancel this plan. The French lost two ''Redoutable''-class submarines during the  The French fleet endured significant losses in the autumn of 1942 during

The French fleet endured significant losses in the autumn of 1942 during  On 9 November a number of the French submarines at Toulon, ''Casabianca'', ''Redoutable'', ''Glorieux'', ''Pascal'' and received authorization from the German and Italian armistice commissions to undergo rearming. On 11 November the Germans enacted ''

On 9 November a number of the French submarines at Toulon, ''Casabianca'', ''Redoutable'', ''Glorieux'', ''Pascal'' and received authorization from the German and Italian armistice commissions to undergo rearming. On 11 November the Germans enacted ''

By the end of 1942, the last six "grand patrol submarines" – ''Archimède'', ''Casabianca'', ''Le Centaure'' ''Le Glorieux'', and ''Protée'' – were in Africa. ''Protée'', which had been serving with the naval squadron as part of with the British fleet at

By the end of 1942, the last six "grand patrol submarines" – ''Archimède'', ''Casabianca'', ''Le Centaure'' ''Le Glorieux'', and ''Protée'' – were in Africa. ''Protée'', which had been serving with the naval squadron as part of with the British fleet at

battleships-cruisers.co.uk

{{WWII French ships Submarine classes Ship classes of the French Navy

French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

. Most of the class saw service during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

is also known in French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

as the ''Classe 1 500 tonnes'', and they were designated as "First Class submarines", or " large submarine cruisers". They are known as the ''Redoutable'' class in reference to the lead boat

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

, in service from 1931 to 1942. The class is divided into two sub-class series, Type I, known as ''Le Redoutable'' and Type II, ''Pascal''.

Although these were modern submarines when they were designed, they quickly became outdated and were approaching obsolescence by the beginning of the Second World War. The conditions of the Armistice of 22 June 1940

The Armistice of 22 June 1940 was signed at 18:36 near Compiègne, France, by officials of Nazi Germany and the Third French Republic. It did not come into effect until after midnight on 25 June.

Signatories for Germany included Wilhelm Keitel ...

prevented the Vichy government

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

from carrying out a modernization programme. 24 out of the 29 units that served in the war were lost. Used in the defence of the Second French colonial empire

The French colonial empire () comprised the overseas colonies, protectorates and mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "First French Colonial Empire", that existe ...

under the Vichy regime, submarines of the class saw action against Allied offensives at the Battles of Dakar, Libreville

Libreville is the capital and largest city of Gabon. Occupying in the northwestern province of Estuaire, Libreville is a port on the Komo River, near the Gulf of Guinea. As of the 2013 census, its population was 703,904.

The area has been inh ...

and Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

. Many of the submarines of the class came under Allied control after the Allied landings in North Africa

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – 16 November 1942) was an Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa while all ...

. Few however saw much further active service after this due to a period of refitting and alterations done in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

between February 1943 and March 1945. One exception was , which took part in the liberation of Corsica

Italian-occupied Corsica refers to the military (and administrative) occupation by the Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Kingdom of Italy of the island of Corsica during the Second World War, from November 1942 to September 1943. After an initial period ...

. The surviving submarines were largely used for training purposes after the war, with the last of them being disarmed in 1952.

Development

Context

The

The Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

of 1922 sought to prevent a future naval arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and t ...

by imposing limits on the number and size of certain types of warships that each great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

could possess. France sought to expand its submarine forces – which were not limited by the treaty – as an essential tool to defend its coastline and empire. The 1100-ton s, designed in 1922, was the initial attempt to meet these requirements; however, the speed of the submarines was notably insufficient and the design overall was considered inferior to the last German submarines

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

launched in 1918.

The design for the ''Requin'' class's successor was commissioned from general engineer of maritime engineering Léon Roquebert. Roquebert was tasked with creating a "grand cruiser" type of submarine, with the role of carrying out surveillance of an adversary's bases, destroying their communications by attacking their ships, while protecting French colonies. They were operate with a surface squadron and provide clearance of enemy vessels for it.

Construction of the Type I project submarines, starting with , was approved by the superior council of the navy on 1 July 1924. The building programme was expanded the following year with the Type II submarines. Together with the submarine cruiser , the ''Redoutable''-class submarines constituted the elite of the French submarine fleet.

Characteristics

long, with abeam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a draught of , the ''Redoutable''-class submarines could dive up to , although several, such as reached depths of while diving.

The submarines had a surfaced displacement of and a submerged displacement of . Propulsion while surfaced was provided by two diesel motors for the ''Redoutable'' sub-class, while the ''Pascal'' variant boats had , while the submarines from ''Agosta'' onwards had , with a maximum speed of . Motors were built by the Swiss manufacturer Sulzer, with the exception of ''Pasteur'', , ''Archimède'', , , , , ''Persée'' and , which were propelled with Schneider

Schneider may refer to:

Hospital

* Schneider Children's Medical Center of Israel

People

* Schneider (surname)

Companies and organizations

* G. Schneider & Sohn, a Bavarian brewery company

* Schneider Rundfunkwerke AG, the former owner of th ...

motors. The submarines' electrical propulsion allowed them to attain speeds of

while submerged. Designated as "grand cruise submarines" (french: « sous-marins de grande croisière »), their surfaced range was at , and at , with a submerged range of at . Radio communication was through wireless antenna.

The ''Redoutable''-class submarines had significant firepower. They were equipped with eleven torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s: four tubes in fixed positions in the bow, an orientable platform for three 550 mm tubes behind the conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

, and another orientable platform on the stern composed of two 550 mm and two tubes. The 550 mm torpedoes were intended for use against large ships, with the 400 mm torpedoes for smaller boats. Torpedoes were propelled by compressed air at a speed of , exploding on impact. Torpedoes left a trail on the surface, which allowed the target to see and avoid the torpedo, as well as trace the torpedo back to its origin. The submarines were also fitted with a deck gun, mounted in front of the conning tower and from 1929, dual anti-aerial machine guns.

The ''Redoutable''-class submarines had a quick diving speed, submerging in between 30 and 40 seconds. They had a reputation of handling well while at sea, both at the surface and while diving. Their motors were relatively noisy, as was auxiliary propulsion while submerged, and this constituted the principal criticism of these submarines, despite their reliability. Their speed and powerful armament was balanced against their ability to detect targets, which was essentially by visual sight. They were equipped with three periscope

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with ...

s – an attack periscope, a surveillance periscope, and an auxiliary periscope – and a hydrophone

A hydrophone ( grc, ὕδωρ + φωνή, , water + sound) is a microphone designed to be used underwater for recording or listening to underwater sound. Most hydrophones are based on a piezoelectric transducer that generates an electric potenti ...

for passive sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigation, navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect o ...

.

History

Construction and early service

The large construction program made it necessary to contract work out to private shipyards, such as those at

The large construction program made it necessary to contract work out to private shipyards, such as those at Caen

Caen (, ; nrf, Kaem) is a commune in northwestern France. It is the prefecture of the department of Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inhabitants (), while its functional urban area has 470,000,Loire

The Loire (, also ; ; oc, Léger, ; la, Liger) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône ...

, as well as the various naval bases. The construction orders were spread over six annual tranches. Small technical alterations were made to the design between orders, utilizing experience gained from previous batches. This did not prevent delays in delivery, which for some orders lasted up to two years and generated design disparities. This absence of standardization had consequences for the maintenance of the submarines, particularly during the Second World War. Laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

on 1 July 1925, the first submarine, ''Redoutable'', was launched on 24 February 1928, and placed in service by 10 July 1931. The 31st and last of the series to be laid down, , entered service on 1 January 1937. ''Ouessant'' and were the last to enter service, on 1 January 1939, because of mounting delays at Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Feb ...

.

The submarines underwent substantial modifications throughout the 1930s, particularly regarding navigational abilities. They conducted training patrols and port visits in the Antilles

The Antilles (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy; es, Antillas; french: Antilles; nl, Antillen; ht, Antiy; pap, Antias; Jamaican Patois: ''Antiliiz'') is an archipelago bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the south and west, the Gulf of Mex ...

, along the African coast or in Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

. Two were lost in accidents before the Second World War: sank during trials

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, w ...

off the Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

coast on 7 July 1932, while was lost off Indochina on 15 June 1939.

Second World War

First actions

At the beginning of Second World War, the ''Pascal''-type vessels were divided between the First Navy Squadron at

At the beginning of Second World War, the ''Pascal''-type vessels were divided between the First Navy Squadron at Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

*Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

*Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

**Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Brest, ...

and the Second Squadron at Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

. They were assigned to operate with their respective squadrons, attack or capture enemy ships, and protect the Franco-British lines of communication. Two ''Redoutable''-type boats were based at Cherbourg. Designed in 1920s, they were still reliable boats, but were becoming obsolete. They were vulnerable to attacks: their submerged propulsion systems were sensitive to bombardment, their maximum diving depth was limited and became insufficient during the conflict, and their underwater sound systems were weak. They formed 40% of the French submarine fleet, composed of a total of 77 naval vessels.

Between September 1939 and June 1940, the French submarines patrolled in the Northern seas and the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

, particularly off the neutral ports of Spain, the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

, and the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

, where part of the German merchant marine had sought refuge, and were suspected of supporting German U-boats. Unlike the German submarine force, French officers were ordered to respect the terms of the London Naval Treaty

The London Naval Treaty, officially the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, was an agreement between the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Italy, and the United States that was signed on 22 April 1930. Seeking to address is ...

: the submarines had to announce their presence to merchant ships prior to an attack, and could only fire on the ship when the crew had evacuated it. These precautionary measures reduced the effectiveness of the French submarine force. ''Redoutable'' encountered a merchant vessel sailing without lights during the night of 1 November. The vessel refused to comply with a request from the submarine to stop, so the submarine fired warning shots with her 100 mm deck gun. The merchant vessel returned fire. ''Redoutable'' then received a message from the British cargo ship ''Egba'', which was reporting that she was under attack by a "U-boat". Realising that the merchant ship she was firing on was a British one, ''Redoutable'' ceased the attack.

In December 1939, , , ''Redoutable'', and ''Le Héros'' were sent into the Atlantic to search for the German tanker , which had been supplying the German cruiser . ''Altmark'', carrying prisoners taken from ships attacked by the German cruiser, evaded detection and sailed towards Norway, where it was eventually captured by British ships in the ''Altmark'' incident. During the winter of 1939–1940, ''Achille'', ''Casabianca'', ''Pasteur'', and escorted three Allied convoys from Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

to the United Kingdom. They were relieved in February by and ''Sidi-Ferruch'', and then, in April, by ''Archimède'' and ''Ajax''.

Italy declared war on France on 10 June 1940. ''Fresnel'', ''Le Tonnant'', ''Redoutable'', and ''Vengeur'' patrolled along the Tunisian coast to prevent an Italian landing, while ''Centaure'' and ''Pascal'' conducted surveillance operations south of Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

. ''Archimède'' participated in Operation Vado

The Italian invasion of France (10–25 June 1940), also called the Battle of the Alps, was the first major Italian engagement of World War II and the last major engagement of the Battle of France.

The Italian entry into the war widened its sc ...

. With the German advance in June, the port of Cherbourg and the arsenal of Brest were evacuated, ships principally heading towards Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

and Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

. On 18 June ''Agosta'', ''Achille'', ''Ouessant'' and ''Pasteur'' were scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

in the port of Brest, having been prevented from putting to sea.

By the time the armistice was signed on 22 June 1940, not one of the 29 ''Redoutable'' class had sunk any German or Italian ships. Only ''Poncelet'' had had any success, her crew having boarded the merchant vessel ''Chemnitz'' and sailed her to Casablanca. The cause of this lack of success was the utilization of the submarines as ''escorteur

The French term ''Escorteur'' (Escort Ship) appeared during the Second World War to designate a warship, of a medium or light displacement, whose mission was to protect ocean convoys and naval squadrons from attacks by submarines. This role was ...

s'' and squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, ...

''eclaireurs'', instead of as ''chasseurs'', in strict adherence to the terms of the Treaty of London, coupled with problems associated with the age and obsolescence of the vessels.

Vichy service

The conditions of the armistice envisaged the return of French naval vessels to their home ports to be disarmed; however, the British attack on Mers-el-Kébir on 3 July convinced the Germans to cancel this plan. The French lost two ''Redoutable''-class submarines during the

The conditions of the armistice envisaged the return of French naval vessels to their home ports to be disarmed; however, the British attack on Mers-el-Kébir on 3 July convinced the Germans to cancel this plan. The French lost two ''Redoutable''-class submarines during the Battle of Dakar

The Battle of Dakar, also known as Operation Menace, was an unsuccessful attempt in September 1940 by the Allies to capture the strategic port of Dakar in French West Africa (modern-day Senegal). It was hoped that the success of the operation cou ...

on 23 and 24 September; on 23 September ''Persée'' was sunk by two British destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s after having tried to torpedo unsuccessfully; on 24 September ''Ajax'' was fired upon by several destroyers escorting the British squadron and was consequently scuttled after the crew abandoned ship. In both cases, the crews were rescued by the British. On 25 September ''Bévéziers'', under the command of ''Capitaine de corvette'' Lancelot, attacked and damaged the battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

, which was out of service for almost nine months.

On 28 October the French naval forces were re-constituted under Vichy government control, under the direction of the German and Italian armistice commissions. Only the Second Submarine Division, consisting of ''Casabianca'', ''Sfax'', ''Bévéziers'' and ''Sidi-Ferruch'', based in Casablanca, and the four submarines sent to Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

, ''Vengeur'', , ''Monge'' and remained armed. The remainder of the ''Redoutable'' class were to be placed under guard at Toulon. Those submarines on active service were relieved one after the other in pairs by units from Toulon, in order to conduct necessary repairs and refits. Defective parts were replaced; however the terms of the armistice prevented upgrades to extend their fighting capabilities.

''Poncelet'' was scuttled on 7 November 1940 during the battle of Libreville after having been damaged by a British sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

. The submarine launched one torpedo against , which the sloop avoided. Severely damaged, ''Poncelet'' surfaced and the crew was ordered to evacuate by the captain. However, Commandant Bertrand de Sausssine du Pont de Gault preferred to remain on board and went down with the submarine. Following the attacks of Mers el-Kébir, Dakar and Libreville, the ''Redoutable''-class submarines were redeployed to Toulon, Casablanca, Dakar, Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, جيبوتي ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red ...

, Madagascar and Indochina to defend the French colonies

From the 16th to the 17th centuries, the First French colonial empire stretched from a total area at its peak in 1680 to over , the second largest empire in the world at the time behind only the Spanish Empire. During the 19th and 20th centuri ...

. ''Sfax'' was accidentally sunk by the with the replenishment ship ''Rhône'' on 19 December, while they were en route to Dakar to reinforce the fleet based there.

In October 1941, a convoy of four French cargo ships en route towards Dakar was captured by the British. As a reprisal, the French sent ''Le Glorieux'' and ''Le Héros'' to attack British commerce off the coast of South Africa. On 15 November ''Le Glorieux'' unsuccessfully attacked a cargo vessel off Port Elizabeth

Gqeberha (), formerly Port Elizabeth and colloquially often referred to as P.E., is a major seaport and the most populous city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is the seat of the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality, Sou ...

. Two days later, ''Le Héros'' sank the cargo vessel ''Thode Fagelund'' off East London, Eastern Cape

East London ( xh, eMonti; af, Oos-Londen) is a city on the southeast coast of South Africa in the Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality of the Eastern Cape province. The city lies on the Indian Ocean coast, largely between the Buffalo River ...

.

On 31 July 1941, the Japanese invaded French Indochina, where they seized ''Pégase'', which was returning from a mission. Concerned about a possible Japanese attack on Madagascar, which would compromise the security of the supply lines to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, the British led an attack on Diego-Suarez, the principal French base, beginning on 5 May 1942. During the attack, three ''Redoutable''-class submarines were sunk: ''Bévéziers'', and ''Le Héros'' by Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also used ...

and ''Monge'' by destroyers. ''Monge'', after having launched one torpedo at the , was spotted, fired upon by three destroyers and sunk.

The French fleet endured significant losses in the autumn of 1942 during

The French fleet endured significant losses in the autumn of 1942 during Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

and the scuttling of the French fleet in Toulon

The scuttling of the French fleet at Toulon was orchestrated by Vichy France on 27 November 1942 to prevent Nazi German forces from taking it over. After the Allied invasion of North Africa the Germans invaded the territory administered by Vic ...

. In one month, eleven naval vessels were lost by being sunk or scuttled, in addition to the three submarines sunk during the Battle of Madagascar in May 1942. French forces in North Africa were taken by surprise when the Allied landings began on the morning of 8 November. At Casablanca, the ''Le Tonnant'', ''Le Conquérant'' and ''Sidi-Ferruch'' came under heavy attack from American aircraft. The commander of ''Le Tonnant'', ''Lieutenant de vaissau'' Paumier, was killed, and the commander of ''Sidi-Ferruch'', ''Capitaine de corvette'' Laroze, was wounded. On 9 November ''Le Tonnant'' launched her last torpedoes against the aircraft carrier , but the carrier evaded them. ''Le Tonnant'' was ordered to head to Toulon, but realising that this was impossible, her captain had the crew disembark off Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

, and then scuttled the submarine. Despite the ceasefire proclaimed on 11 November, ''Le Conquérant'' and ''Sidi-Ferruch'' were sunk by American aircraft on 13 November. At Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

, the submarines ''Actéon'' and ''Fresnel'' put to sea on the night of 8 November. ''Actéon'' was sunk a couple of hours later by depth charges from the British destroyer . ''Fresnel'' attacked the cruiser , which avoided the torpedoes. Pursued and under attack for the next three days, ''Fresnel'' managed evade her attackers and returned to Toulon on 13 November.

Case Anton

Case Anton (german: link=no, Fall Anton) was the military occupation of France carried out by Germany and Italy in November 1942. It marked the end of the Vichy regime as a nominally-independent state and the disbanding of its army (the severel ...

'' and moved their forces into the Vichy-controlled area of France. French Navy personnel had to decide between their oath of fidelity to Marshal Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of World ...

, and their desire to join the Allies in Algeria. Admirals André Marquis

André Marquis (24 October 1883 – 15 October 1957) was a French Vichyist admiral, famous for the scuttling of the French fleet in Toulon.

Marquis was of Toulon, and as such, responsible for the administration of the city. He was captured by ...

, maritime prefect of Toulon, and Jean de Laborde

Jean de Laborde (29 November 1878 – 30 July 1977) was a French admiral who had a long career starting at the end of the 19th century and extending to World War II after which he was convicted of treason and sentenced to death. A pioneer of Fren ...

, commander-in-chief of the Toulon squadron, ordered preparations to defend Toulon against an Anglo-American assault, having the Germans' assurance that Toulon would not be occupied. At the same time, they put in place the necessary orders and counter-measures that would ensure the scuttling of the entire fleet, to keep it out of foreign hands, while conforming to an order from Admiral François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service d ...

dated 24 June 1940. Towards 0430 on 27 November a German force arrived at the arsenal gate, with orders to secure control of the French fleet. The alarm was raised and Admiral de Laborde ordered the immediate scuttling of all naval vessels present at Toulon, based on an order given by another French admiral on 11 November 1942.

Nine ''Redoutable''-class submarines were at Toulon: ''Fresnel'', , ''Vengeur'', and ''L'Espoir'' were in dry docks and the ''Casabianca'', ''Le Glorieux'', ''Redoutable'', ''Henri Poincare'', and ''Pascal'' were afloat in the northern bunkers of Mourillon. The last three were not ready for sea and only ''Le Glorieux'' and ''Casabianca'' had installed their new batteries as well a full load of fuel. As soon as the first shots were fired, the commanders of ''Le Glorieux'' and ''Casabianca'' moved away from the docks and navigated their submarines towards the exits of the port on electric motors, accompanied by the 600-ton submarine , the and the ''Requin''-class ''Marsouin'', while under fire from the Germans. Unable to reach the sea, ''Redoutable'', ''Henri Poincaré'', ''Pascal'' and ''Fresnel'' were scuttled by opening the hatches. ''Achéron'', ''Vengeur'' and ''L'Espoir'' were sunk by flooding their dry docks. They were later dismantled and scrapped

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered me ...

at Toulon or the Italian port of La Spezia

La Spezia (, or , ; in the local Spezzino dialect) is the capital city of the province of La Spezia and is located at the head of the Gulf of La Spezia in the southern part of the Liguria region of Italy.

La Spezia is the second largest city ...

, or utilized as floats.

Already having put to sea from Brest on 17 June 1940, the commander of ''Casabianca'' had to choose between scuttling his boat in deep waters or sailing to an Allied port to continue the war. ''Casabianca'' sailed to Algiers, reaching there on 30 November and joining the Allied forces. ''Le Glorieux'' arrived at Oran the same day after a brief stop at Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

.

Service with the Allies

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

since the armistice in 1940, joined the French fleet in June 1942. The submarines from Africa were assigned to the 8th British Submarine Squadron, then from November 1943, the 10th Squadron. The captured ''Pégase'' was commissioned by the Japanese and stationed in Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

, and then disarmed on 1 January 1944.

Because of their capabilities, the French submarines were principally used by the Allies for missions involving information gathering, and the loading or unloading of personnel or material. ''Casabianca'', the only operational ''Redoutable''-class submarine during most of 1943, carried out seven of these types of missions between December 1942 and September 1943, principally off Italian-occupied Corsica

Italian-occupied Corsica refers to the military (and administrative) occupation by the Kingdom of Italy of the island of Corsica during the Second World War, from November 1942 to September 1943. After an initial period of increased control over th ...

. On 1 July 1943 she landed resistance leader Paulin Colonna d'Istria Paulin Colonna d'Istria (27 July 1905 – 4 June 1982) was a French Gendarmerie officer, awarded the Compagnon de la Libération after playing a major part in the liberation of Corsica.

Early life

Colonna d'Istria was born on 27 July 1905 in Petre ...

and 13 tons of material at the beach at Saleccia. On 13 September ''Casabianca'' landed 109 men of the and their equipment at Ajaccio

Ajaccio (, , ; French: ; it, Aiaccio or ; co, Aiacciu , locally: ; la, Adiacium) is a French commune, prefecture of the department of Corse-du-Sud, and head office of the ''Collectivité territoriale de Corse'' (capital city of Corsica). ...

. Between June and July she also carried out several unsuccessful attacks on the 10,000-ton merchant vessel ''Champagne''.

''Protée'' sailed to Algiers via Oran in November. On her first mission from Algiers she unsuccessfully attacked a German cargo ship. At some point between 18 and 25 December she struck a mine

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

* Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

...

off Marseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

and was lost with all hands. It was assumed for some time that ''Protée'' had been sunk in an engagement with a German ship while surfaced. However, in 1995 Henri-Germain Delauze, aboard ''Remora 2000'', dived on ''Protée''s wreck and confirmed United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

suspicions from the 1950s that ''Protée'' had been sunk by a mine. There was also no record of an engagement with a German vessel listed in German archives. On 22 December 1943 ''Casabianca'' sank a submarine chaser

A submarine chaser or subchaser is a small naval vessel that is specifically intended for anti-submarine warfare. Many of the American submarine chasers used in World War I found their way to Allied nations by way of Lend-Lease in World War II.

...

between Cape Cépet and Cape Sicié. A couple of days later ''Casabianca'' torpedoed and damaged the cargo ship ''Ghisone'', which was able to sail to Toulon. On 9 June 1944, ''Casabianca'' attacked a German submarine chaser with her deck gun and torpedoes off Cape Camarat, but was unable to seriously damage the vessel. ''Casabianca'' gained the nickname "ghost submarine" (french: «le sous-marin fantôme») from the Germans, and was allowed by the 8th Submarine Squadron to fly the Jolly Roger

Jolly Roger is the traditional English name for the flags flown to identify a pirate ship preceding or during an attack, during the early 18th century (the later part of the Golden Age of Piracy).

The flag most commonly identified as the Jolly ...

in 1943.

In December 1942 an accord was reached between U.S. and French authorities for the transfer, one by one, of the ''Redoutable''-class submarines to the United States for refitting and modernization, given that their design was by now almost twenty years old. The motors were overhauled, the batteries changed, and the pressure hulls and diving auxiliaries reinforced. The ballasts were also reworked to improve the range of the boats. Efforts were made to improve the soundproofing the submarines. The submarines were equipped with radar, underwater sound systems, better performing asdic

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect objects on or ...

, bathythermograph

The bathythermograph, or BT, also known as the Mechanical Bathythermograph, or MBT; is a device that holds a temperature sensor and a transducer to detect changes in water temperature versus depth down to a depth of approximately 285 meters (9 ...

s and other capabilities. The living conditions were improved with the installation of air conditioning and a refrigerator. The conning tower was modified, with the removal of various navigational features, which were replaced with an anti-aerial armament. The telescopic masts were also removed. ''Archimède'' left Dakar on 8 February 1943 and sailed to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, where she remained for almost a year. Work began in May at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard

The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard was an important naval shipyard of the United States for almost two centuries.

Philadelphia's original navy yard, begun in 1776 on Front Street and Federal Street in what is now the Pennsport section of the cit ...

, but was complicated by the lack of blueprint

A blueprint is a reproduction of a technical drawing or engineering drawing using a contact print process on light-sensitive sheets. Introduced by Sir John Herschel in 1842, the process allowed rapid and accurate production of an unlimited number ...

s and schematics. As well as this, the four surviving submarines used two different types of motor – an issue which caused problems for the American engineers. However, they were impressed by the modern fabrication of the nearly twenty year old boats. Alterations to ''Archimède'' were completed on 19 February 1944, and she was replaced in the shipyard by ''Le Glorieux'' until July, then ''Le Centaure'' from 2 June to 18 December and finally ''Casabianca'' from 2 August 1944 to 30 March 1945. The last two refits were less through than the first. ''Argo'' was deemed in too poor condition for a complete overhaul, and was transferred for use as a training boat for American submariners.

After returning from the United States, ''Archimède'' carried out surveillance missions and intelligence operations between March and August 1944. In April and June the boat landed and embarked several assets on the Spanish coast. On 12 May she mistaken for a German U-boat and was attacked by three British aircraft. ''Archimède'' escaped after submerging . During the night of 13 and 14 July ''Archimède'' was spotted by a Wassermann radar

The Wasserman radar was an early-warning radar built by Germany during World War II. The radar was a development of Freya radar, FuMG 80 Freya and was operated during World War II for long range detection. It was developed under the direction of ...

off Cape Dramont and chased by three anti-submarine patrol boats for three hours. On 16 July ''Archimède'' located a small German convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

and fired four torpedoes against an aviso

An ''aviso'' was originally a kind of dispatch boat or "advice boat", carrying orders before the development of effective remote communication.

The term, derived from the Portuguese and Spanish word for "advice", "notice" or "warning", an '' ...

which was saved by its draught, which was less than the running depth of the French mechanically launched torpedoes. On 10 August the submarines left the French coast in anticipation of Operation Dragoon

Operation Dragoon (initially Operation Anvil) was the code name for the landing operation of the Allied invasion of Provence (Southern France) on 15August 1944. Despite initially designed to be executed in conjunction with Operation Overlord, th ...

. By now the submarine war in the Mediterranean was largely over. By the time the French submarines were operating there German traffic had drastically reduced, and there were few targets for them.

After the return of ''Casabianca'' and ''Argo'' to the Mediterranean during the spring of 1945, the five ''Redoutable''-class submarines passed the remainder of the war carrying out training exercises at Oran, while awaiting a transfer to the Pacific. The surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ...

on 2 September 1945 meant this never took place. Of the twenty-nine submarines active in 1939, twenty-four had been sunk or scuttled during the war. For their service ''Casabianca'' received the Resistance Medal

The Resistance Medal (french: Médaille de la Résistance) was a decoration bestowed by the French Committee of National Liberation, based in the United Kingdom, during World War II. It was established by a decree of General Charles de Gaulle on 9 ...

with ''rosette'' and the ''fourragère

The ''fourragère'' () is a military award, distinguishing military units as a whole, in the form of a braided cord. The award was first adopted by France, followed by other nations such as the Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, and Luxembourg. Fou ...

'' of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon, ...

, while ''Le Glorieux'' received the Resistance Medal.

Post-war

''Pégase'' was disarmed in Saigon by the Japanese on 1 January 1944, then scuttled on 9 March 1945. The boat was refloated in September; however, she was put up for disposal in 1950 without ever having entered service again. The following year she was beached on the Bassac sandbank in theMekong Delta

The Mekong Delta ( vi, Đồng bằng Sông Cửu Long, lit=Nine Dragon River Delta or simply vi, Đồng Bằng Sông Mê Kông, lit=Mekong River Delta, label=none), also known as the Western Region ( vi, Miền Tây, links=no) or South-weste ...

to serve as a seamark

A sea mark, also seamark and navigation mark, is a form of aid to navigation and pilotage that identifies the approximate position of a maritime channel, hazard, or administrative area to allow boats, ships, and seaplanes to navigate safely.

Th ...

. By now obsolete, ''Argo'' was disarmed in April 1946.

The four remaining ''Redoutable''-class submarines served as training vessels for new submarine crews, and for destroyers exercising underwater detection. ''Casabianca'' and ''Le Centaure'' carried out a cruise along the African coast and returned to Brest in January 1947. The scheduled large refitting for the two submarines was cancelled in June and were both placed in special reserve on 1 December 1947, before being disarmed; ''Casabianca'' on 12 February 1952 and ''Le Centaure'' on 19 June.

''Archimède'' and ''Le Glorieux'' spent six months being refitted at Cherbourg from January 1946. Their equipment was inspected, and then repaired or replaced. Following their trials, they were based at Brest in January 1947, then carried out a four-month cruise off Africa in company with ''U-2518'', a former German Type XXI submarine

Type XXI submarines were a class of German diesel–electric ''Elektroboot'' (German: "electric boat") submarines designed during the Second World War. One hundred and eighteen were completed, with four being combat-ready. During the war only tw ...

transferred to the French Navy in order to assess her capabilities. From 1947 to 1949 the two ''Redoutable''-class submarines conducted training exercises at Brest, then at Toulon. ''Archimède'' was placed in special reserve on 31 August 1949, then disarmed on 19 February 1952. ''Le Glorieux'' was used for the filming of ''Casabianca'' in 1949, and was then placed in reserve. The last ''Redoutable''-class submarine was disarmed on 27 October 1952.

The ''Redoutable''-class submarines were replaced in the French Navy by German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s, such as ''U-2518'', which became , or British S-class submarines. The first submarines developed in France after the Second World War were the ''Narval'' class, which entered service in 1957. The four ''Redoutable''-class submarines had been scrapped by 1956. In 1953, the conning tower of ''Casabianca'' was installed as a commemorative monument in the courtyard palace of the former governors of Bastia

Bastia (, , , ; co, Bastìa ) is a commune in the department of Haute-Corse, Corsica, France. It is located in the northeast of the island of Corsica at the base of Cap Corse. It also has the second-highest population of any commune on the is ...

. The monument became increasingly dilapidated, and an identical replica was forged in 2002 and placed in the Saint-Nicolas Square in Bastia in October 2003.

List of ''Redoutable''-class submarines

Successes

See also

*Georges Cabanier

Admiral Georges Cabanier (21 November 1906 – 26 October 1976) was a French Naval Officer and Admiral, in addition to Grand Chancellor of the Legion of Honour.

Military career

Entered into the École Navale in 1925, he navigated on several n ...

References

Sources

* * *Further reading

* * * * *External links

battleships-cruisers.co.uk

{{WWII French ships Submarine classes Ship classes of the French Navy