Õż¦µŚźµ£¼ÕĖØÕ£ŗķÖĖĶ╗Ź µŁ®ÕģĄĶü»ķÜŖĶ╗ŹµŚŚ on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the

On 27 January 1868, tensions between the shogunate and imperial sides came to a head when

On 27 January 1868, tensions between the shogunate and imperial sides came to a head when

After the defeat of the Tokugawa shogunate and operations in Northeastern Honshu and Hokkaido a true national army did not exist. Many in the restoration coalition had recognized the need for a strong centralized authority and although the imperial side was victorious, the early Meiji government was weak and the leaders had to maintain their standing with their domains whose military forces was essential for whatever the government needed to achieve. The leaders of the restoration were divided over the future organization of the army. ┼īmura Masujir┼Ź who had sought a strong central government at the expense of the domains advocated for the creation of a standing national army along European lines

under the control of the

After the defeat of the Tokugawa shogunate and operations in Northeastern Honshu and Hokkaido a true national army did not exist. Many in the restoration coalition had recognized the need for a strong centralized authority and although the imperial side was victorious, the early Meiji government was weak and the leaders had to maintain their standing with their domains whose military forces was essential for whatever the government needed to achieve. The leaders of the restoration were divided over the future organization of the army. ┼īmura Masujir┼Ź who had sought a strong central government at the expense of the domains advocated for the creation of a standing national army along European lines

under the control of the

In March 1871, the War Ministry announced the creation of an

In March 1871, the War Ministry announced the creation of an

The

The  Initially, because of the army's small size and numerous exemptions, relatively few young men were actually conscripted for a three-year term on active duty. In 1873, the army numbered approximately 17,900 from a population of 35 million at the time; it doubled to about 33,000 in 1875. The conscription program slowly built up the numbers. Public unrest began in 1874, reaching the apex in the

Initially, because of the army's small size and numerous exemptions, relatively few young men were actually conscripted for a three-year term on active duty. In 1873, the army numbered approximately 17,900 from a population of 35 million at the time; it doubled to about 33,000 in 1875. The conscription program slowly built up the numbers. Public unrest began in 1874, reaching the apex in the

The Japanese invasion of

The Japanese invasion of  By the 1890s, the Imperial Japanese Army had grown to become the most modern army in Asia: well-trained, well-equipped, and with good morale. However, it was basically an

By the 1890s, the Imperial Japanese Army had grown to become the most modern army in Asia: well-trained, well-equipped, and with good morale. However, it was basically an

In the early months of 1894, the

In the early months of 1894, the  During the almost two-month interval prior to the declaration of war, the two service staffs developed a two-stage operational plan against China. The army's 5th Division would land at Chemulpo to prevent a Chinese advance in Korea while the navy would engage the

During the almost two-month interval prior to the declaration of war, the two service staffs developed a two-stage operational plan against China. The army's 5th Division would land at Chemulpo to prevent a Chinese advance in Korea while the navy would engage the

The RussoŌĆōJapanese War (1904ŌĆō1905) was the result of tensions between

The RussoŌĆōJapanese War (1904ŌĆō1905) was the result of tensions between

During 1917ŌĆō18, Japan continued to extend its influence and privileges in China via the Nishihara Loans.

During the Siberian Intervention, following the collapse of the

During 1917ŌĆō18, Japan continued to extend its influence and privileges in China via the Nishihara Loans.

During the Siberian Intervention, following the collapse of the

In 1931, the Imperial Japanese Army had an overall strength of 198,880 officers and men, organized into 17 divisions.

The Manchurian incident, as it became known in Japan, was a pretended sabotage of a local Japanese-owned railway, an attack staged by Japan but blamed on Chinese dissidents. Action by the military, largely independent of the civilian leadership, led to the invasion of

In 1931, the Imperial Japanese Army had an overall strength of 198,880 officers and men, organized into 17 divisions.

The Manchurian incident, as it became known in Japan, was a pretended sabotage of a local Japanese-owned railway, an attack staged by Japan but blamed on Chinese dissidents. Action by the military, largely independent of the civilian leadership, led to the invasion of

April 13, 1941. (

Battlefield (documentary series), 2001, 98 minutes.

From 1943, Japanese troops suffered from a shortage of supplies, especially food, medicine, munitions, and armaments, largely due to

From 1943, Japanese troops suffered from a shortage of supplies, especially food, medicine, munitions, and armaments, largely due to

File:Gen. Ichiro Suganami (1895-1960) & Lieut. Saburo Suganami (1904ŌĆō1985).jpg, IJA Japanese officers, 1930s

File:IJA Special Volunteers by Korean people.JPG, IJA Korean Volunteer army, 1943

File:Õ£©ĶÅ▓Ķć║ń▒ŹµŚźµ£¼ÕģĄ Taiwanese soldier during World War II.jpg, IJA Taiwanese soldier in Philippines during World War II

Throughout the

Throughout the

* 1870: consisted of 12,000 men.

* 1873: Seven divisions of c. 36,000 men (c. 46,250 including reserves)

* 1885: consisted of seven divisions including the

* 1870: consisted of 12,000 men.

* 1873: Seven divisions of c. 36,000 men (c. 46,250 including reserves)

* 1885: consisted of seven divisions including the

online

* Fr├╝hst├╝ck, Sabine. (2007) ''Uneasy warriors: Gender, memory, and popular culture in the Japanese army'' (Univ of California Press, 2007). * Gruhl, Werner. (2010) ''Imperial Japan's World War Two: 1931ŌĆō1945'' (Transaction Publishers). * * Kublin, Hyman. "The 'Modern' Army of Early Meiji Japan". ''The Far Eastern Quarterly'', 9#1 (1949), pp. 20ŌĆō41. * Kuehn, John T. (2014) ''A Military History of Japan: From the Age of the Samurai to the 21st Century'' (ABC-CLIO, 2014). * Norman, E. Herbert. "Soldier and Peasant in Japan: The Origins of Conscription." ''Pacific Affairs'' 16#1 (1943), pp. 47ŌĆō64. * * Rottman, Gordon L. (2013) ''Japanese Army in World War II: Conquest of the Pacific 1941ŌĆō42'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013). * Rottman, Gordon L. (2012) ''Japanese Infantryman 1937ŌĆō45: Sword of the Empire'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012). * Sisemore, Major James D. (2015) ''The Russo-Japanese War, Lessons Not Learned'' (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015). * Storry, Richard. (1956) "Fascism in Japan: The Army Mutiny of February 1936" ''History Today'' (Nov 1956) 6#11 pp 717ŌĆō726. * Wood, James B. (2007) ''Japanese Military Strategy in the Pacific War: Was Defeat Inevitable?'' (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007). * Yenne, Bill. (2014) ''The Imperial Japanese Army: The Invincible Years 1941ŌĆō42'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014).

online

384pp; highly detailed description of wartime IJA by U.S. Army Intelligence.

Overview of Imperial Japanese Army weapons and armaments in World War II

Army of the Land of the Rising Sun 100 years ago. Part 1. Leap from the Middle Ages into the XX century

(part 1 of 4)

Imperial Japanese Army 3rd Platoon reenactor's resource

Eastern menace: the story of Japanese imperialism

{{Authority control 1868 establishments in Japan 1945 disestablishments in Japan

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as┬Āthe Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From JapanŌĆōKor ...

from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in JapanŌĆÖs rapid modernization during the Meiji period

The was an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868, to July 30, 1912. The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonizatio ...

, fought in numerous conflicts including the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 189417 April 1895), or the First ChinaŌĆōJapan War, was a conflict between the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Joseon, Korea. In Chinese it is commonly known as th ...

, the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 ŌĆō 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

, World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 ŌĆō 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912ŌĆō1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

, and World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 ŌĆō 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, and became a dominant force in Japanese politics. Initially formed from domain armies after the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

, it evolved into a powerful modern military influenced by French and German models. The IJA was responsible for several overseas military campaigns, including the invasion of Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

, involvement in the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious F ...

, and fighting across the Asia-Pacific during the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the AsiaŌĆōPacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

. Notorious for committing widespread war crimes

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hos ...

, the army was dissolved after Japan's surrender in 1945, and its functions were succeeded by the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force

The , , also referred to as the Japanese Army, is the land warfare branch of the Japan Self-Defense Forces. Created on July 1, 1954, it is the largest of the three service branches.

New military guidelines, announced in December 2010, direct ...

.

History

Origins (1868ŌĆō1871)

In the mid-19th century, Japan had no unified national army and the country was made up of feudal domains (''han'') with theTokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868.

The Tokugawa shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, ending the civil wars ...

(''bakufu'') in overall control, which had ruled Japan since 1603. The bakufu army, although a large force, was only one among others, and bakufu efforts to control the nation depended upon the cooperation of its vassals' armies. The opening of the country after two centuries of seclusion subsequently led to the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

and the Boshin War

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a coalition seeking to seize political power in the name of the Impe ...

in 1868. The domains of Satsuma and Ch┼Źsh┼½ came to dominate the coalition against the shogunate.

Boshin War

On 27 January 1868, tensions between the shogunate and imperial sides came to a head when

On 27 January 1868, tensions between the shogunate and imperial sides came to a head when Tokugawa Yoshinobu

Kazoku, Prince was the 15th and last ''sh┼Źgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan. He was part of a movement which aimed to reform the aging shogunate, but was ultimately unsuccessful. He resigned his position as shogun in late 1867, while ai ...

marched on Kyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Ky┼Źto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

, accompanied by a 15,000-strong force, some of which had been trained by French military advisers. They were opposed by 5,000 troops from the Satsuma, Ch┼Źsh┼½, and Tosa domains. At the two road junctions of Toba and Fushimi just south of Kyoto, the two forces clashed. On the second day, an Imperial banner was given to the defending troops and a member of the Imperial Family, the Prince Ninnaji, was named nominal commander in chief, in effect making the pro-imperial forces officially an The bakufu forces eventually retreated to Osaka, with the remaining forces ordered to retreat to Edo. Yoshinobu and his closest advisors left for Edo by ship. The encounter at TobaŌĆōFushimi between the imperial and shogunate forces marked the beginning of the conflict. With the court in Kyoto firmly behind the Satsuma-Ch┼Źsh┼½-Tosa coalition, other domains that were sympathetic to the causesuch as Tottori (''Inaba''), Aki (''Hiroshima''), and Hizen (''Saga'')emerged to take a more active role in military operations. Western domains that had either supported the shogunate or remained neutral also quickly announced their support of the restoration movement.

The nascent Meiji state required a new military command for its operations against the shogunate. In 1868, the "Imperial Army" being just a loose amalgam of domain armies, the government created four military divisions: the T┼Źkaid┼Ź, T┼Źsand┼Ź

is a Japanese geographical term. It means both an ancient division of the country and the main road running through it. It is part of the ''Gokishichid┼Ź'' system. It was situated along the central mountains of northern Honshu, specifically th ...

, San'ind┼Ź

is a Japanese geographical term. It means both an ancient division of the country and the main road running through it. ''San'in'' translates to "the shaded side of a mountain", while ''d┼Ź'', depending on the context, can mean either a road, o ...

, and Hokurikud┼Ź, each of which was named for a major highway. Overseeing these four armies was a new high command, the Eastern Expeditionary High Command (''T┼Źsei dais┼Ź tokufu''), whose nominal head was prince Arisugawa-no-miya

The was one of the shinn┼Źke, branches of the Imperial Family of Japan which were, until 1947, eligible to succeed to the Chrysanthemum Throne in the event that the main line should die out.

History

The Arisugawa-no-miya house was founded by Pr ...

, with two court nobles as senior staff officers. This connected the loose assembly of domain forces with the imperial court, which was the only national institution in a still unformed nation-state. The army continually emphasized its link with the imperial court: firstly, to legitimize its cause; secondly, to brand enemies of the imperial government as enemies of the court and traitors; and, lastly, to gain popular support. To supply food, weapons, and other supplies for the campaign, the imperial government established logistical relay stations along three major highways. These small depots held stockpiled material supplied by local pro-government domains, or confiscated from the bakufu and others opposing the imperial government. Local villagers were routinely impressed as porters to move and deliver supplies between the depots and frontline units.

Struggles to form a centralized army

Initially, the new army fought under makeshift arrangements, with unclear channels of command and control and no reliable recruiting base. Although fighting for the imperial cause, many of the units were loyal to their domains rather than the imperial court. In March 1869, the imperial government created various administrative offices, including a military branch; and in the following month organized an imperial bodyguard of 400 to 500, which consisted of Satsuma and Ch┼Źsh┼½ troops strengthened by veterans of the encounter at TobaŌĆōFushimi, as well as yeoman and masterless samurai from various domains. The imperial court told the domains to restrict the size of their local armies and to contribute to funding a national officers' training school in Kyoto. However, within a few months the government disbanded both the military branch and the imperial bodyguard: the former was ineffective while the latter lacked modern weaponry and equipment. To replace them, two new organizations were created. One was the military affairs directorate which was composed of two bureaus, one for the army and one for the navy. The directorate drafted an army from troop contributions from each domain proportional to each domain's annual rice production (''koku''). This conscript army (''ch┼Źheigun'') integrated samurai and commoners from various domains into its ranks. As the war continued, the military affairs directorate expected to raise troops from the wealthier domains and, in June, the organization of the army was fixed, where each domain was required to send ten men for each 10,000 koku of rice produced. However, this policy put the imperial government in direct competition with the domains for military recruitment, which was not rectified until April 1868, when the government banned the domains from enlisting troops. Consequently, the quota system never fully worked as intended and was abolished the following year. The Imperial forces encountered numerous difficulties during the war, especially during the campaign in Eastern Japan. Headquarters in faraway Kyoto often proposed plans at odds with the local conditions, which led to tensions with officers in the field, who in many cases ignored centralized direction in favor of unilateral action. The army lacked a strong central staff that was capable of enforcing orders. Consequently, military units were at the mercy of individual commanders' leadership and direction. This was not helped by the absence of a unified tactical doctrine, which left units to fight according to the tactics favored by their respective commanders. There was increased resentment by many lower ranked commanders as senior army positions were monopolized by thenobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

together with samurai from Ch┼Źsh┼½ and Satsuma. The use of commoners within the new army created resentment among the samurai class. Although the nascent Meiji government achieved military success, the war left a residue of disgruntled warriors and marginalized commoners, together with a torn social fabric.

Foundation of a national army (1871ŌĆō1873)

After the defeat of the Tokugawa shogunate and operations in Northeastern Honshu and Hokkaido a true national army did not exist. Many in the restoration coalition had recognized the need for a strong centralized authority and although the imperial side was victorious, the early Meiji government was weak and the leaders had to maintain their standing with their domains whose military forces was essential for whatever the government needed to achieve. The leaders of the restoration were divided over the future organization of the army. ┼īmura Masujir┼Ź who had sought a strong central government at the expense of the domains advocated for the creation of a standing national army along European lines

under the control of the

After the defeat of the Tokugawa shogunate and operations in Northeastern Honshu and Hokkaido a true national army did not exist. Many in the restoration coalition had recognized the need for a strong centralized authority and although the imperial side was victorious, the early Meiji government was weak and the leaders had to maintain their standing with their domains whose military forces was essential for whatever the government needed to achieve. The leaders of the restoration were divided over the future organization of the army. ┼īmura Masujir┼Ź who had sought a strong central government at the expense of the domains advocated for the creation of a standing national army along European lines

under the control of the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

, the introduction of conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

for commoners and the abolition of the samurai class. ┼īkubo Toshimichi

┼īkubo Toshimichi (; 26 September 1830 ŌĆō 14 May 1878) was a Japanese statesman and samurai of the Satsuma Domain who played a central role in the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the Three Great Nobles of the Restoration (ńČŁµ¢░Ńü«õĖ ...

preferred a small volunteer force consisting of former samurai. ┼īmura's views for modernizing Japan's military led to his assassination in 1869 and his ideas were largely implemented after his death by Yamagata Aritomo

Prince was a Japanese politician and general who served as prime minister of Japan from 1889 to 1891, and from 1898 to 1900. He was also a leading member of the '' genr┼Ź'', a group of senior courtiers and statesmen who dominated the politics ...

. Aritomo has been described as the father of the Imperial Japanese Army. Yamagata had commanded mixed commoner-samurai Ch┼Źsh┼½ units during the Boshin War and was convinced of the merit of peasant soldiers. Although he himself was part of the samurai class, albeit of insignificant lower status, Yamagata distrusted the warrior class, several members of whom he regarded as clear dangers to the Meiji state.

Establishment of the Imperial Guard and institutional reforms

In March 1871, the War Ministry announced the creation of an

In March 1871, the War Ministry announced the creation of an Imperial Guard

An imperial guard or palace guard is a special group of troops (or a member thereof) of an empire, typically closely associated directly with the emperor and/or empress. Usually these troops embody a more elite status than other imperial force ...

(''Goshinpei'') of six thousand men, consisting of nine infantry battalions, two artillery batteries and two cavalry squadrons. The emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

donated 100,000 ry┼Ź

The was a gold currency unit in the shakkanh┼Ź system in pre- Meiji Japan. It was eventually replaced with a system based on the '' yen''.

Origins

The ''ry┼Ź'' was originally a unit of weight from China, the ''tael.'' It came into use in Ja ...

to underwrite the new unit, which was subordinate to the court. It was composed of members of the Satsuma, Ch┼Źsh┼½ and Tosa domains, who had led the restoration. Satsuma provided four battalions of infantry and four artillery batteries; Ch┼Źsh┼½ provided three battalions of infantry; Tosa two battalions of infantry, two squadrons of cavalry, and two artillery batteries. For the first time, the Meiji government was able to organize a large body of soldiers under a consistent rank and pay scheme with uniforms, which were loyal to the government rather than the domains. The Imperial Guard's principal mission was to protect the throne by suppressing domestic samurai revolts, peasant uprisings and anti-government demonstrations. The possession of this military force was a factor in the government's abolition of the han system

The in the Empire of Japan and its replacement by a system of prefectures in 1871 was the culmination of the Meiji Restoration begun in 1868, the starting year of the Meiji period. Under the reform, all daimyos (, ''daimy┼Ź'', feudal lords) ...

.

The military ministry (''Hy┼Źbush┼Ź'') was reorganized in July 1871; on August 29, simultaneously with the decree abolishing the domains, the Daj┼Źkan ordered local daimyos to disband their private armies and turn their weapons over to the government. Although the government played on the foreign threat, especially Russia's southward expansion, to justify a national army, the immediately perceived danger was domestic insurrection. Consequently, on August 31, the country was divided into four military districts, each with its own chindai (''garrison'') to deal with peasant uprisings or samurai insurrections. The Imperial Guard formed the Tokyo garrison, whereas troops from the former domains filled the ranks of the Osaka, Kumamoto, and Sendai garrisons. The four garrisons had a total of about 8,000 troopsmostly infantry, but also a few hundred artillerymen and engineers. Smaller detachments of troops also guarded outposts at Kagoshima, Fushimi, Nagoya, Hiroshima, and elsewhere. By late December 1871, the army set modernization and coastal defense as priorities; long-term plans were devised for an armed force to maintain internal security, defend strategic coastal areas, train and educate military and naval officers, and build arsenals and supply depots. Despite previous rhetoric about the foreign menace, little substantive planning was directed against Russia. In February 1872, the military ministry was abolished and separate army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

and navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

ministries were established.

Conscription

The

The conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

ordinance enacted on January 10, 1873, made universal military service compulsory for all male subjects in the country. The law called for a total of seven years of military service: three years in the regular army (''j┼Źbigun''), two years in the reserve (''dai'ichi k┼Źbigun''), and an additional two years in the second reserve (''daini k┼Źbigun''). All able-bodied males between the ages of 17 and 40 were considered members of the national guard (''kokumingun''), which would only see service in a severe national crisis, such as an attack or invasion of Japan. The conscription examination decided which group of recruits would enter the army, those who failed the exam were excused from all examinations except for the national guard. Recruits who passed entered the draft lottery, where some were selected for active duty. A smaller group would be selected for replacement duty (''hoj┼½-eki'') should anything happen to any of the active duty soldiers; the rest were dismissed. One of the primary differences between the samurai and the peasant class was the right to bear arms; this ancient privilege was suddenly extended to every male in the nation. There were several exemptions, including criminals, those who could show hardship, the physically unfit, heads of households or heirs, students, government bureaucrats, and teachers. A conscript could also purchase an exemption for ┬ź270, which was an enormous sum for the time and which restricted this privilege to the wealthy. Under the new 1873 ordinance, the conscript army was composed mainly of second and third sons of impoverished farmers who manned the regional garrisons, while former samurai controlled the Imperial Guard and the Tokyo garrison.

Initially, because of the army's small size and numerous exemptions, relatively few young men were actually conscripted for a three-year term on active duty. In 1873, the army numbered approximately 17,900 from a population of 35 million at the time; it doubled to about 33,000 in 1875. The conscription program slowly built up the numbers. Public unrest began in 1874, reaching the apex in the

Initially, because of the army's small size and numerous exemptions, relatively few young men were actually conscripted for a three-year term on active duty. In 1873, the army numbered approximately 17,900 from a population of 35 million at the time; it doubled to about 33,000 in 1875. The conscription program slowly built up the numbers. Public unrest began in 1874, reaching the apex in the Satsuma Rebellion

The Satsuma Rebellion, also known as the , was a revolt of disaffected samurai against the new imperial government of the Empire of Japan, nine years into the Meiji era. Its name comes from the Satsuma Domain, which had been influential in ...

of 1877, which used the slogans, "oppose conscription", "oppose elementary schools", and "fight Korea". It took a year for the new army to crush the uprising, but the victories proved critical in creating and stabilizing the Imperial government and to realize sweeping social, economic and political reforms that enabled Japan to become a modern state that could stand comparison to France, Germany, and other Western European powers.

Further development and modernization (1873ŌĆō1894)

Foreign assistance

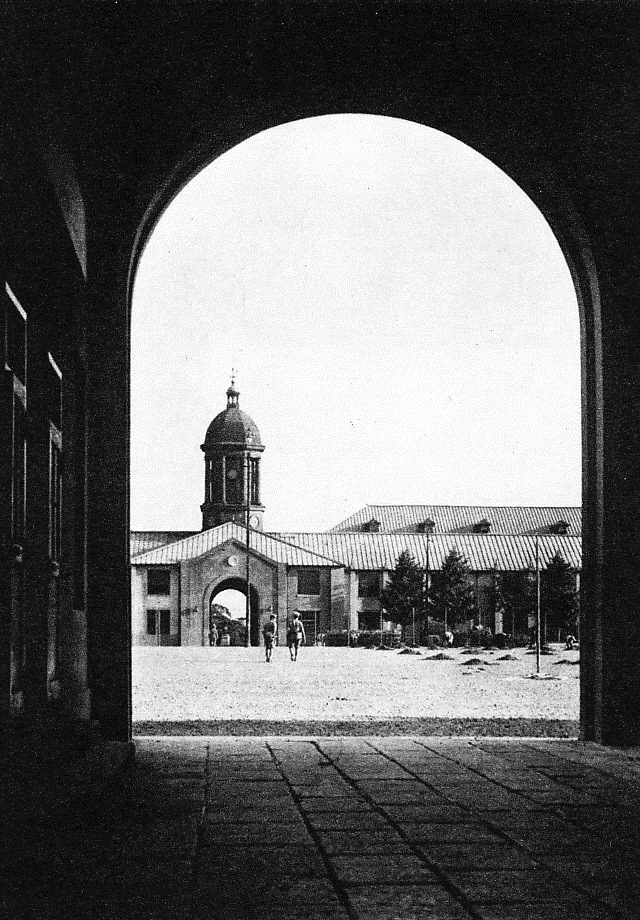

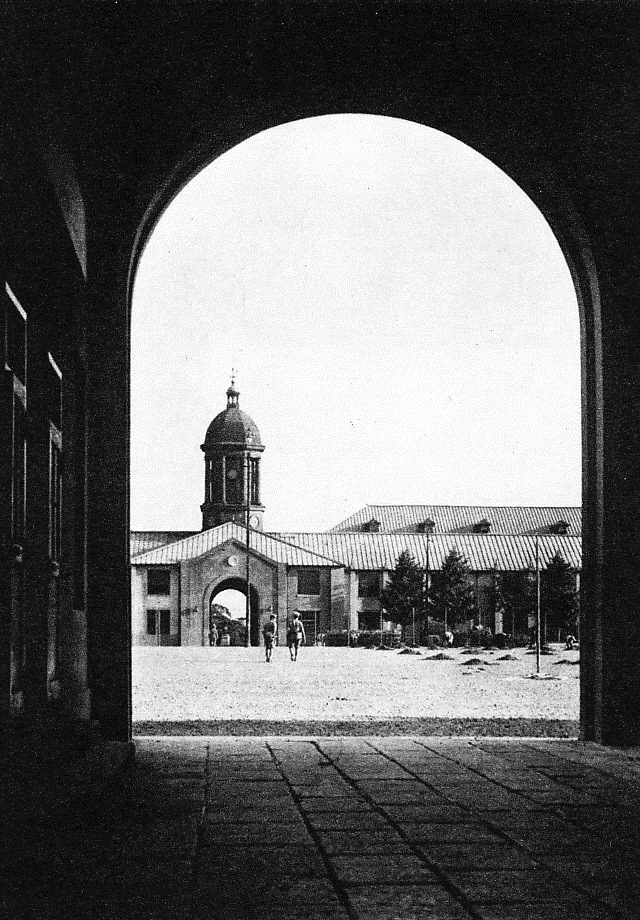

The early Imperial Japanese Army was developed with the assistance of advisors from France, through the second French military mission to Japan (1872ŌĆō80), and the third French military mission to Japan (1884ŌĆō89). However, after France's defeat in 1871 the Japanese government switched to the victorious Germans as a model. From 1886 to April 1890, it hired German military advisors (Major Jakob Meckel, replaced in 1888 by von Wildenbr├╝ck and Captain von Blankenbourg) to assist in the training of the Japanese General Staff. In 1878, the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office, based on theGerman General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the Imperial German Army, German Army, responsible for the continuous stu ...

, was established directly under the Emperor and was given broad powers for military planning and strategy.

Other known foreign military consultants were Major Pompeo Grillo from the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

, who worked at the Osaka foundry from 1884 to 1888, followed by Major Quaratezi from 1889 to 1890; and Captain Schermbeck from the Netherlands, who worked on improving coastal defenses from 1883 to 1886. Japan did not use foreign military advisors between 1890 and 1918, until the French military mission to Japan (1918ŌĆō19)

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

, headed by Commandant Jacques-Paul Faure, was requested to assist in the development of the Japanese air services.

Taiwan Expedition

The Japanese invasion of

The Japanese invasion of Taiwan under Qing rule

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of Chi ...

in 1874 was a punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong beha ...

by Japanese military forces in response to the Mudan Incident

The Japanese punitive expedition to Taiwan in 1874, referred to in Japan as the and in Taiwan and mainland China as the Mudan incident (), was a punitive expedition launched by the Japanese ostensibly in retaliation for the murder of 54 Ryū ...

of December 1871. The Paiwan people

The Paiwan () are an indigenous people of Taiwan. They speak the Paiwan language. In 2014, the Paiwan numbered 96,334. This was approximately 17.8% of Taiwan's total indigenous population, making them the second-largest indigenous group.

The ma ...

, who are indigenous peoples of Taiwan, murdered 54 crewmembers of a wrecked merchant vessel from the Ryukyu Kingdom

The Ryukyu Kingdom was a kingdom in the Ryukyu Islands from 1429 to 1879. It was ruled as a Tributary system of China, tributary state of Ming dynasty, imperial Ming China by the King of Ryukyu, Ryukyuan monarchy, who unified Okinawa Island t ...

on the southwestern tip of Taiwan. 12 men were rescued by the local Chinese-speaking community and were transferred to Miyako-jima in the Ryukyu Islands. The Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as┬Āthe Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From JapanŌĆōKor ...

used this as an excuse to both assert sovereignty over the Ryukyu Kingdom, which was a tributary state of both Japan and Qing China at the time, and to attempt the same with Taiwan, a Qing territory. It marked the first overseas deployment of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy.

An Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors of 1882 called for unquestioning loyalty to the Emperor by the new armed forces and asserted that commands from superior officers were equivalent to commands from the Emperor himself. Thenceforth, the military existed in an intimate and privileged relationship with the imperial institution.

Top-ranking military leaders were given direct access to the Emperor and the authority to transmit his pronouncements directly to the troops. The sympathetic relationship between conscripts and officers, particularly junior officers who were drawn mostly from the peasantry, tended to draw the military closer to the people. In time, most people came to look more for guidance in national matters more to military than to political leaders.

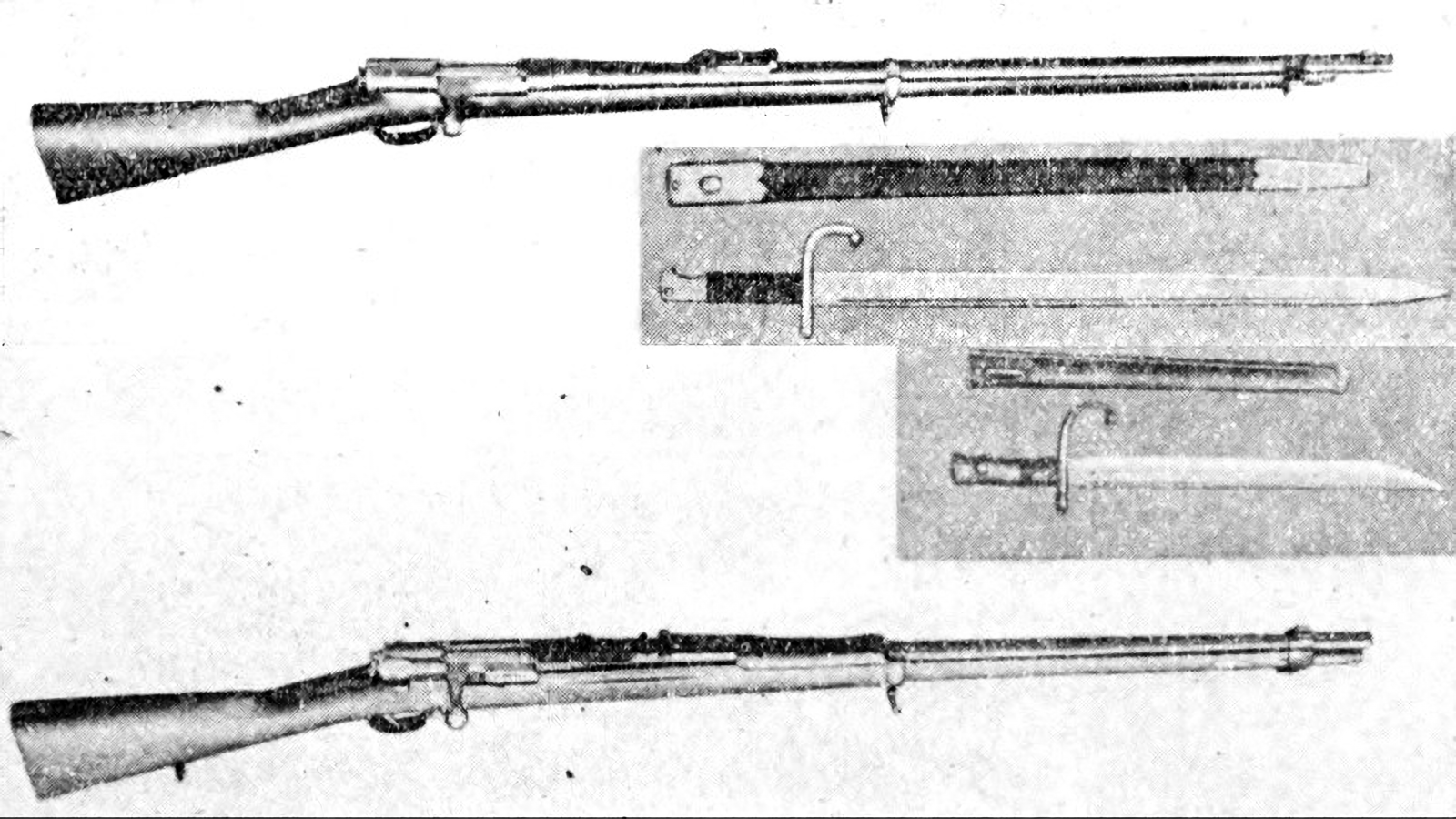

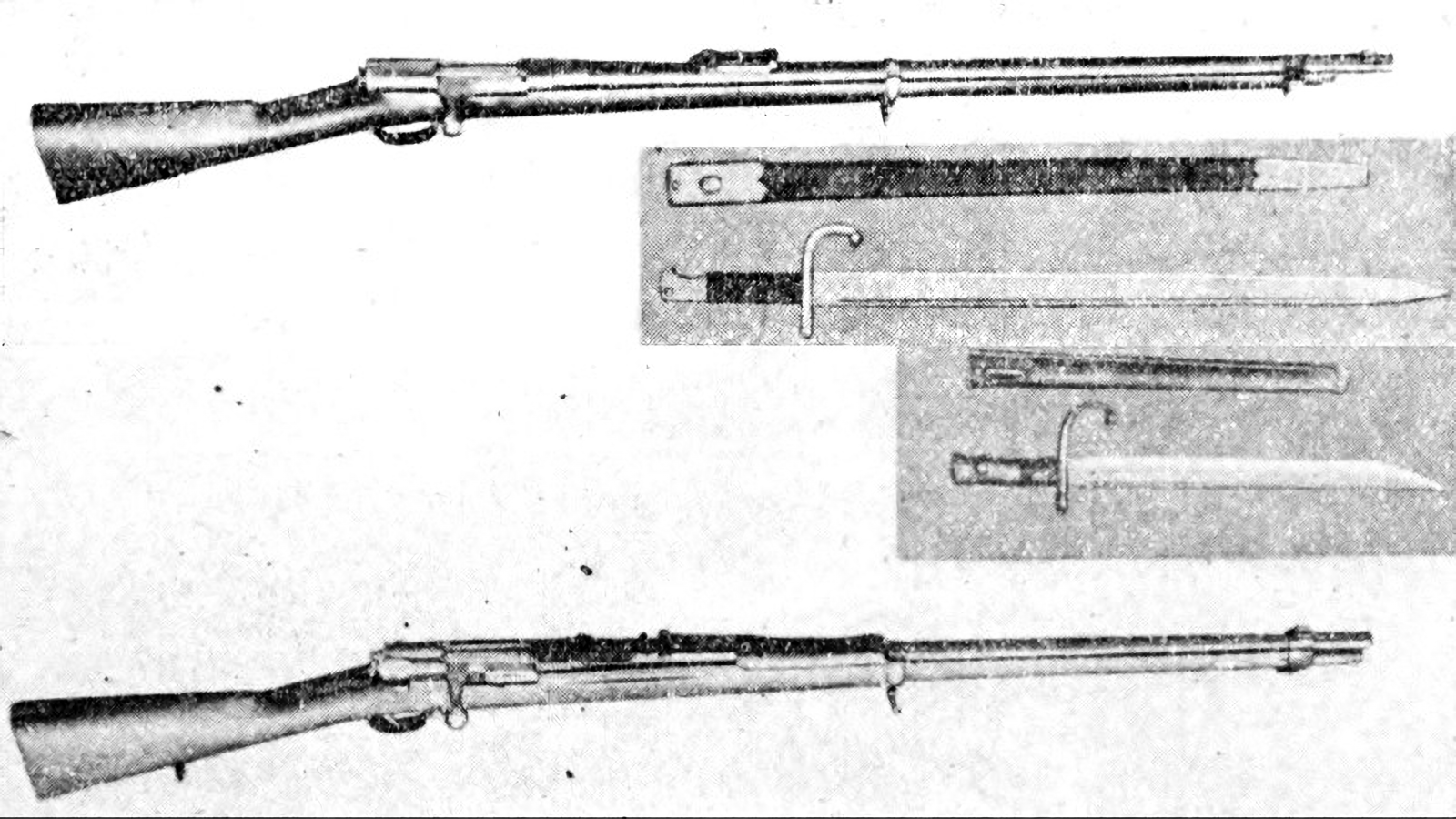

By the 1890s, the Imperial Japanese Army had grown to become the most modern army in Asia: well-trained, well-equipped, and with good morale. However, it was basically an

By the 1890s, the Imperial Japanese Army had grown to become the most modern army in Asia: well-trained, well-equipped, and with good morale. However, it was basically an infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

force deficient in cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

and artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

when compared with its European contemporaries. Artillery pieces, which were purchased from America and a variety of European nations, presented two problems: they were scarce, and the relatively small number that were available were of several different caliber

In guns, particularly firearms, but not #As a measurement of length, artillery, where a different definition may apply, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel Gauge ( ...

s, causing problems with ammunition supply.

First Sino-Japanese War

In the early months of 1894, the

In the early months of 1894, the Donghak Peasant Revolution

The Donghak Peasant Revolution () was a peasant revolt that took place between 11 January 1894 and 25 December 1895 in Korea. The peasants were primarily followers of Donghak, a Neo-Confucian movement that rejected Western technology and i ...

broke out in southern Korea and had soon spread throughout the rest of the country, threatening the Korea capital Seoul

Seoul, officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City, is the capital city, capital and largest city of South Korea. The broader Seoul Metropolitan Area, encompassing Seoul, Gyeonggi Province and Incheon, emerged as the world's List of cities b ...

, itself. The Chinese, since the beginning of May had taken steps to prepare the mobilization of their forces in the provinces of Zhili

Zhili, alternately romanized as Chihli, was a northern administrative region of China since the 14th century that lasted through the Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty until 1911, when the region was dissolved, converted to a province, and renamed ...

, Shandong

Shandong is a coastal Provinces of China, province in East China. Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilization along the lower reaches of the Yellow River. It has served as a pivotal cultural ...

and in Manchuria, as a result of the tense situation on the Korean peninsula. These actions were planned more as an armed demonstration intended to strengthen the Chinese position in Korea, rather than as a preparation for war with Japan. On June 3, the Chinese government accepted the requests from the Korean government to send troops to help quell the rebellion, additionally they also informed the Japanese of the action. It was decided to send 2,500 men to Asan

Asan (; ) is a Administrative divisions of South Korea, city in South Chungcheong Province, South Korea. It borders the Seoul Capital Area to the north. Asan has a population of approximately 400,000.

Asan is known for its many hot springs an ...

, about 70 km from the capital Seoul. The troops arrived in Asan on June 9 and were additionally reinforced by 400 more on June 25, a total of about 2,900 Chinese soldiers were at Asan.

From the very outset the developments in Korea had been carefully observed in Tokyo. Japanese government had soon become convinced that the Donghak Peasant Revolution would lead to Chinese intervention in Korea. As a result, soon after learning word about the Korean government's request for Chinese military help, immediately ordered all warships in the vicinity to be sent to Pusan and Chemulpo. On June 9, a formation of 420 ''rikusentai'', selected from the crews of the Japanese warships was immediately dispatched to Seoul, where they served temporarily as a counterbalance to the Chinese troops camped at Asan. Simultaneously, the Japanese decided to send a reinforced brigade of approximately 8,000 troops to Korea. The reinforced brigade, included auxiliary units, under the command of General Oshima Yoshimasa was fully transported to Korea by June 27. The Japanese stated to the Chinese that they were willing to withdraw the brigade under General Oshima if the Chinese left Asan prior. However, when on 16 July, 8,000 Chinese troops landed near the entrance of the Taedong River

The Taedong River () is a large river in North Korea. The river rises in the Rangrim Mountains of the country's north where it then flows southwest into Korea Bay at Namp'o.Suh, Dae-Sook (1987) "North Korea in 1986: Strengthening the Soviet ...

to reinforce Chinese troops garrisoned in Pyongyang

Pyongyang () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of North Korea, where it is sometimes labeled as the "Capital of the Revolution" (). Pyongyang is located on the Taedong River about upstream from its mouth on the Yellow Sea. Accordi ...

, the Japanese delivered Li Hongzhang

Li Hongzhang, Marquess Suyi ( zh, t=µØÄķ┤╗ń½Ā; also Li Hung-chang; February 15, 1823 ŌĆō November 7, 1901) was a Chinese statesman, general and diplomat of the late Qing dynasty. He quelled several major rebellions and served in importan ...

an ultimatum, threatening to take action if any further troops were sent to Korea. Consequently, General Oshima in Seoul and commanders of the Japanese warships in Korean waters received orders allowing them to initiate military operations if any more Chinese troops were sent to Korea. Despite this ultimatum, Li, considered that Japanese were bluffing and were trying to probe the Chinese readiness to make concessions. He decided, therefore to reinforce Chinese forces in Asan with a further 2,500 troops, 1,300 of which arrived in Asan during the night of July 23ŌĆō24. At the same time, in the early morning of July 23, the Japanese had taken control of the Royal Palace in Seoul and imprisoned King Gojong, forcing him to renounce ties with China.

During the almost two-month interval prior to the declaration of war, the two service staffs developed a two-stage operational plan against China. The army's 5th Division would land at Chemulpo to prevent a Chinese advance in Korea while the navy would engage the

During the almost two-month interval prior to the declaration of war, the two service staffs developed a two-stage operational plan against China. The army's 5th Division would land at Chemulpo to prevent a Chinese advance in Korea while the navy would engage the Beiyang fleet

The Beiyang Fleet (Pei-yang Fleet; , alternatively Northern Seas Fleet) was one of the Imperial Chinese Navy#Fleets, four modernized Chinese navies in the late Qing dynasty. Among the four, the Beiyang Fleet was particularly sponsored by Li Hong ...

in a decisive battle in order to secure control of the seas. If the navy defeated the Chinese fleet decisively and secured command of the seas, the larger part of the army would undertake immediate landings on the coast between Shanhaiguan and Tianjin, and advance to the Zhili

Zhili, alternately romanized as Chihli, was a northern administrative region of China since the 14th century that lasted through the Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty until 1911, when the region was dissolved, converted to a province, and renamed ...

plain in order to defeat the main Chinese forces and bring the war to a swift conclusion. If neither side gained control of the sea and supremacy, the army would concentrate on the occupation of Korea and exclude Chinese influence there. Lastly, if the navy was defeated and consequently lost command of the sea, Japanese forces in Korea would be ordered to hang on and fight a rearguard action while the bulk of the army would remain in Japan in preparation to repel a Chinese invasion. This worst-case scenario also foresaw attempts to rescue the beleaguered 5th Division in Korea while simultaneously strengthening homeland defenses. The army's contingency plans which were both offensive and defensive, depended on the outcome of the naval operations.

Clashes between Chinese and Japanese forces at Pungdo and Seongwhan caused irreversible changes to Sino-Japanese relations and meant that a state of war now existed between the two countries. The two governments officially declared war on August 1. Initially, the general staff's objective was to secure the Korean peninsula before the arrival of winter and then land forces near Shanhaiguan. However, as the navy was unable to bring the Beiyang fleet into battle in mid-August, temporarily withdrew from the Yellow Sea to refit and replenish its ships. As a consequence, in late August the general staff ordered an advance overland to the Zhili plain via Korea in order to capture bases on the Liaodong Peninsula to prevent Chinese forces from interfering with the drive on Beijing. The First Army with two divisions was activated on September 1. In mid-September 17, the Chinese forces defeated at Pyongyang

Pyongyang () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of North Korea, where it is sometimes labeled as the "Capital of the Revolution" (). Pyongyang is located on the Taedong River about upstream from its mouth on the Yellow Sea. Accordi ...

and occupied the city, as the remaining Chinese troops retreated northward. The navy's stunning victory in the Yalu on September 17, was crucial to the Japanese as it allowed the Second Army with three divisions and one brigade to land unopposed on the Liaodong Peninsula about 100 miles north of Port Arthur which controlled the entry to the Bohai Gulf, in mid-October. While, the First Army pursued the remaining Chinese forces from Korea across the Yalu River, Second Army occupied the city of Dairen

Dalian ( ) is a major sub-provincial port city in Liaoning province, People's Republic of China, and is Liaoning's second largest city (after the provincial capital Shenyang) and the third-most populous city of Northeast China (after Shenyang ...

on November 8 and then seized the fortress and harbor at Port Arthur on November 25. Farther north, the First army's offensive stalled and was beset by supply problems and winter weather.

Boxer Rebellion

In 1899ŌĆō1900, Boxer attacks against foreigners in China intensified, resulting in the siege of the diplomatic legations inBeijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

. An international force consisting of British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

, French, Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

, Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

, American, and Japanese troops was eventually assembled to relieve the legations. The Japanese provided the largest contingent of troops, 20,840, as well as 18 warships.

A small, hastily assembled, vanguard force of about 2,000 troops, under the command of British Admiral Edward Seymour, departed by rail, from Tianjin, for the legations in early June. On June 12, mixed Boxer and Chinese regular army forces halted the advance, some 30 miles from the capital. The road-bound and badly outnumbered allies withdrew to the vicinity of Tianjin

Tianjin is a direct-administered municipality in North China, northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the National Central City, nine national central cities, with a total population of 13,866,009 inhabitants at the time of the ...

, having suffered more than 300 casualties. The army general staff in Tokyo became aware of the worsening conditions in China and had drafted ambitious contingency plans, but the government, in light of the Triple Intervention refused to deploy large forces unless requested by the western powers. However, three days later, the general staff did dispatch a provisional force of 1,300 troops, commanded by Major General Fukushima Yasumasa, to northern China. Fukushima was chosen because his ability to speak fluent English which enabled him to communicate with the British commander. The force landed near Tianjin on July 5.

On June 17, with tensions increasing, naval ''Rikusentai'' from Japanese ships had joined British, Russian, and German sailors to seize the Dagu forts near Tianjin. Four days later, the Qing court declared war on the foreign powers. The British, in light of the precarious situation, were compelled to ask Japan for additional reinforcements, as the Japanese had the only readily available forces in the region. Britain at the time was heavily engaged in the Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, AngloŌĆōBoer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic an ...

, and, consequently, a large part of the British army was tied down in South Africa. Deploying large numbers of troops from British garrisons in India would take too much time and weaken internal security there. Overriding personal doubts, Foreign Minister Aoki Sh┼½z┼Ź calculated that the advantages of participating in an allied coalition were too attractive to ignore. Prime Minister Yamagata likewise concurred, but others in the cabinet demanded that there be guarantees from the British in return for the risks and costs of a major deployment of Japanese troops. On July 6, the 5th Infantry Division was alerted for possible deployment to China, but without a timetable being set. Two days later, on July 8, with more ground troops urgently needed to lift the siege of the foreign legations at Beijing, the British ambassador offered the Japanese government one million British pounds in exchange for Japanese participation.

Shortly afterward, advance units of the 5th Division departed for China, bringing Japanese strength to 3,800 personnel, of the then-17,000 allied force. The commander of the 5th Division, Lt. General Yamaguchi Motoomi, had taken operational control from Fukushima. A second, stronger allied expeditionary army stormed Tianjin, on July 14, and occupied the city. The allies then consolidated and awaited the remainder of the 5th Division and other coalition reinforcements. In early August, the expedition pushed towards the capital where on August 14, it lifted the Boxer siege. By that time, the 13,000-strong Japanese force was the largest single contingent, making up about 40 percent of the approximately 33,000 strong allied expeditionary force. Japanese troops involved in the fighting had acquitted themselves well, although a British military observer felt their aggressiveness, densely packed formations, and over-willingness to attack cost them excessive casualties. For example, during the Tianjin fighting, the Japanese, while comprising less than one quarter (3,800) of the total allied force of 17,000, suffered more than half of the casualties, 400 out of 730. Similarly at Beijing, the Japanese, constituting slightly less than half of the assault force, accounted for almost two-thirds of the losses, 280 of 453.

Russo-Japanese War

The RussoŌĆōJapanese War (1904ŌĆō1905) was the result of tensions between

The RussoŌĆōJapanese War (1904ŌĆō1905) was the result of tensions between Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, grown largely out of rival imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

ambitions toward Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

and Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

. The Japanese army inflicted severe losses against the Russians; however, they were not able to deal a decisive blow to the Russian armies. Over-reliance on infantry led to large casualties among Japanese forces, especially during the siege of Port Arthur.

In 1902, the English, who like the Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

ese after their war with China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, had found themselves isolated owing to Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an condemnation for waging war on the Boers

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, were only too happy to sign a defensive alliance with Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. A condition of this treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by international law. A treaty may also be known as an international agreement, protocol, covenant, convention ...

was that England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

would go to war with any country that joined Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

in a war against Japan. To add more weight to Japanese security, the American President, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 ŌĆō January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, gave a firm warning to France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

that any further bullying on their part towards Japan would result in America coming out firmly on her side.

Confronted by the proposition of having no allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

, and the possibility of incurring the wrath of both America and Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

, The Tsar (Nicholas II) agreed to a staged withdrawal of his forces

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an object to change its velocity unless counterbalanced by other forces. In mechanics, force makes ideas like 'pushing' or 'pulling' mathematically precise. Because the magnitude and directi ...

from Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

. By 1903 however this had been watered down with Russian troops

A troop is a military sub-subunit, originally a small formation of cavalry, subordinate to a Squadron (cavalry), squadron. In many armies a troop is the equivalent element to the infantry section (military unit), section or platoon. Exception ...

still remaining ostensibly to guard their newly constructed railways

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of land transport, next to roa ...

, and also by the creation of the Russian Far East Timber Company which saw the potential of lucrative lumber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into uniform and useful sizes (dimensional lumber), including beams and planks or boards. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, window frames). ...

concessions along the borders of Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

.

World War I

TheEmpire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as┬Āthe Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From JapanŌĆōKor ...

entered the war on the Entente side. Although tentative plans were made to send an expeditionary force of between 100,000 and 500,000 men to fight in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

on the Western Front, ultimately among the few actions in which the Imperial Japanese Army was involved was the careful and well executed attack on the German concession of Qingdao

Qingdao, Mandarin: , (Qingdao Mandarin: t═Ī╔Ģ╩░i┼ŗ╦¦╦® t╔Æ╦ź) is a prefecture-level city in the eastern Shandong Province of China. Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, Qingdao was long an important fortress. In 1897, the city was ceded to G ...

in 1914 and the seizure of various other small German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

islands and colonies.

Inter-war years

Siberian intervention

During 1917ŌĆō18, Japan continued to extend its influence and privileges in China via the Nishihara Loans.

During the Siberian Intervention, following the collapse of the

During 1917ŌĆō18, Japan continued to extend its influence and privileges in China via the Nishihara Loans.

During the Siberian Intervention, following the collapse of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

after the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. It was led by Vladimir L ...

, the Imperial Japanese Army initially planned to send more than 70,000 troops to occupy Siberia as far west as Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal is a rift lake and the deepest lake in the world. It is situated in southern Siberia, Russia between the Federal subjects of Russia, federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast, Irkutsk Oblasts of Russia, Oblast to the northwest and the Repu ...

. The army general staff came to view the Tsarist collapse as an opportunity to free Japan from any future threat from Russia by detaching Siberia and forming an independent buffer state. The plan was scaled back considerably due to opposition from the United States.

In July 1918, the U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, asked the Japanese government to supply 7,000 troops as part of an international coalition of 24,000 troops to support the American Expeditionary Force Siberia. After a heated debate in the Diet, the government of Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Terauchi Masatake agreed to send 12,000 troops, but under the command of Japan, rather than as part of an international coalition. Japan and the United States sent forces to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

to bolster the armies of the White movement

The White movement,. The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds. also known as the Whites, was one of the main factions of the Russian Civil War of 1917ŌĆō1922. It was led mainly by the Right-wing politics, right- ...

leader Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak

List of Russian admirals, Admiral Alexander Vasilyevich Kolchak (; ŌĆō 7 February 1920) was a Russian navy officer and Arctic exploration, polar explorer who led the White movement in the Russian Civil War. As he assumed the title of Supreme Ru ...

against the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

.

Once the political decision had been reached, the Imperial Japanese Army took over full control under Chief of Staff General Yui Mitsue; and by November 1918, more than 70,000 Japanese troops had occupied all ports and major towns in the Russian Maritime Provinces

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of ...

and eastern Siberia.

In June 1920, the United States and its allied coalition partners withdrew from Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( ; , ) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai and the capital of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia. It is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area o ...

, after the capture and execution of the White Army leader, Admiral Kolchak, by the Red Army. However, the Japanese decided to stay, primarily due to fears of the spread of communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

so close to Japan and Japanese-controlled Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

. The Japanese Army provided military support to the Japanese-backed Provisional Priamurye Government, based in Vladivostok, against the Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

-backed Far Eastern Republic

The Far Eastern Republic ( rus, ąöą░ą╗čīąĮąĄą▓ąŠčüč鹊čćąĮą░čÅ ąĀąĄčüą┐čāą▒ą╗ąĖą║ą░, Dal'nevostochnaya Respublika, p=d╔Öl╩▓n╩▓╔¬v╔É╦łstot╔Ģn╔Öj╔Ö r╩▓╔¬s╦łpubl╩▓╔¬k╔Ö, links=yes; ), sometimes called the Chita Republic (, ), was a nominally indep ...

.

The continued Japanese presence concerned the United States, which suspected that Japan had territorial designs on Siberia and the Russian Far East

The Russian Far East ( rus, ąöą░ą╗čīąĮąĖą╣ ąÆąŠčüč鹊ą║ ąĀąŠčüčüąĖąĖ, p=╦łdal╩▓n╩▓╔¬j v╔É╦łstok r╔É╦łs╩▓i╔¬) is a region in North Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asia, Asian continent, and is coextensive with the Far Easte ...

. Subjected to intense diplomatic pressure by the United States and Great Britain, and facing increasing domestic opposition due to the economic and human cost, the administration of Prime Minister Kat┼Ź Tomosabur┼Ź withdrew the Japanese forces in October 1922.

Rise of militarism

In the 1920s the Imperial Japanese Army expanded rapidly and by 1927 had a force of 300,000 men. Unlike western countries, the Army enjoyed a great deal of independence from government. Under the provisions of theMeiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan ( Ky┼½jitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenp┼Ź''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in ...

, the War Minister was held accountable only to the Emperor (Hirohito

, Posthumous name, posthumously honored as , was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, from 25 December 1926 until Death and state funeral of Hirohito, his death in 1989. He remains Japan's longest-reigni ...

) himself, and not to the elected civilian government. In fact, Japanese civilian administrations needed the support of the Army in order to survive. The Army controlled the appointment of the War Minister, and in 1936 a law was passed that stipulated that only an active duty general or lieutenant-general could hold the post. As a result, military spending as a proportion of the national budget rose disproportionately in the 1920s and 1930s, and various factions within the military exerted disproportionate influence on Japanese foreign policy.

The Imperial Japanese Army was originally known simply as the Army (''rikugun'') but after 1928, as part of the Army's turn toward romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

and also in the service of its political ambitions, it re-titled itself the Imperial Army (''k┼Źgun'').

In 1923, the army consisted of 21 divisions, but in accordance with the 1924 reform it was reduced to 17 divisions. Two leaps in the development of the military industry (1906ŌĆō1910 and 1931ŌĆō1934) made it possible to re-equip the armed forces.

Second Sino-Japanese War

In 1931, the Imperial Japanese Army had an overall strength of 198,880 officers and men, organized into 17 divisions.

The Manchurian incident, as it became known in Japan, was a pretended sabotage of a local Japanese-owned railway, an attack staged by Japan but blamed on Chinese dissidents. Action by the military, largely independent of the civilian leadership, led to the invasion of

In 1931, the Imperial Japanese Army had an overall strength of 198,880 officers and men, organized into 17 divisions.

The Manchurian incident, as it became known in Japan, was a pretended sabotage of a local Japanese-owned railway, an attack staged by Japan but blamed on Chinese dissidents. Action by the military, largely independent of the civilian leadership, led to the invasion of Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

in 1931 and, later, to the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912ŌĆō1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

, in 1937. As war approached, the Imperial Army's influence with the Emperor waned and the influence of the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

increased. Nevertheless, by 1938 the Army had been expanded to 34 divisions.

Conflict with the Soviet Union

From 1932 to 1945 the Empire of Japan and theSoviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

had a series of conflicts. Japan had set its military sights on Soviet territory as a result of the ''Hokushin-ron

was a political doctrine of the Empire of Japan before World War II that stated that Manchuria and Siberia were Japan's sphere of interest and that the potential value to Japan for economic and territorial expansionism, expansion in those areas ...

'' doctrine, and the Japanese establishment of a puppet state

A puppet state, puppet r├®gime, puppet government or dummy government is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its ord ...

in Manchuria brought the two countries into conflict. The war lasted on and off with the last battles of the 1930s (the Battle of Lake Khasan

The Battle of Lake Khasan (), also known as the Changkufeng Incident (Chinese and Japanese: zh, s=Õ╝Ąķ╝ōÕ│░õ║ŗõ╗Č, labels=no; Chinese pinyin: zh, hp=Zh─ünggŪöf─ōng Sh├¼ji├Ān, labels=no; Japanese romaji: ), was an attempted military incursion b ...

and the Battles of Khalkhin Gol

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (; ) were the decisive engagements of the undeclared SovietŌĆōJapanese border conflicts involving the Soviet Union, Mongolian People's Republic, Mongolia, Empire of Japan, Japan and Manchukuo in 1939. The conflict wa ...

) ending in a decisive victory for the Soviets. The conflicts stopped with the signing of the SovietŌĆōJapanese Neutrality Pact

The , also known as the , was a non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan signed on April 13, 1941, two years after the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese Border War. The agreement meant that for most of World War II, ...

on April 13, 1941.Soviet-Japanese Neutrality PactApril 13, 1941. (

Avalon Project

The Avalon Project is a digital library of documents relating to law, history and diplomacy. The project is part of the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library.

The project contains online electronic copies of documents dating back to the b ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

) However, later, at the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (), held 4ŌĆō11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. The three sta ...

, Stalin agreed to declare war on Japan; and on August 5, 1945, the Soviet Union voided their neutrality agreement with Japan."Battlefield ŌĆō Manchuria ŌĆō The Forgotten Victory"Battlefield (documentary series), 2001, 98 minutes.

World War II

In 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army had 51 divisions and various special-purpose artillery, cavalry, anti-aircraft, and armored units with a total of 1,700,000 people. At the beginning of theSecond World War