Ă‘ancahuazĂº Guerrilla on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ă‘ancahuazĂº Guerrilla or EjĂ©rcito de LiberaciĂ³n Nacional de Bolivia (''National Liberation Army of Bolivia''; ELN) was a group of mainly

by Juan O. Tamayo, ''Miami Herald'', 19 September 1997. Later on the night of 8 October, Guevara, despite having his hands tied, kicked Bolivian Officer Captain Espinosa into the wall, after the officer entered the schoolhouse in order to snatch Guevara's pipe from his mouth as a souvenir. In another instance of defiance, Guevara spat in the face of Bolivian Rear Admiral Ugarteche shortly before his execution. Captain Prado told Guevara that he would be taken to the city of

A letter sent by Che Guevara from his jungle camp in Bolivia, to the Tricontinental Solidarity Organisation in Havana, Cuba, in the Spring of 1967. Guevara wrote his own

Salvador Allende, internacionalista

. ''Punto Final''. 16 May 2008.

After the failure of Guevara's insurgency, radical leftists in Bolivia began to organize again to set up guerrilla resistance in 1970 in what is known today as the Teoponte Guerrilla.

Fernando GĂ³mez, a former member of the Ă‘ancahuazĂº Guerrilla, led the formation of Salvador Allende's informal bodyguard prior to the

Bolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

n and Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

n guerrillas led by the guerrilla leader Che Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14th May 1928 – 9 October 1967) was an Argentines, Argentine Communist revolution, Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and Military theory, military theorist. A majo ...

which was active in the Cordillera Province of Bolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

from 1966 to 1967. The group established its base camp on a farm across the Ă‘ancahuazĂº River, a seasonal tributary of the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( or ) in the United States or the RĂo Bravo (del Norte) in Mexico (), also known as TĂ³ Ba'Ă¡adi in Navajo language, Navajo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the Southwestern United States a ...

, 250 kilometers southwest of the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra

Santa Cruz de la Sierra (; ), commonly known as Santa Cruz, is the largest city in Bolivia and the capital of the Santa Cruz Department (Bolivia), Santa Cruz department.

Situated on the Pirai River (Bolivia), Pirai River in the eastern Tropical ...

. The guerrillas intended to work as a ''foco

A guerrilla foco is a small cadre of revolutionaries operating in a nation's countryside. This guerrilla organization was popularized by Che Guevara in his book ''Guerrilla Warfare (Che Guevara book), Guerrilla Warfare'', which was based on his e ...

'', a point of armed resistance to be used as a first step to overthrow the Bolivian government and create a socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. This article is about states that refer to themselves as socialist states, and not specifically ...

. The guerrillas defeated several Bolivian patrols before they were beaten and Guevara was captured and executed. Only five guerrillas managed to survive, and fled to Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

.

Background

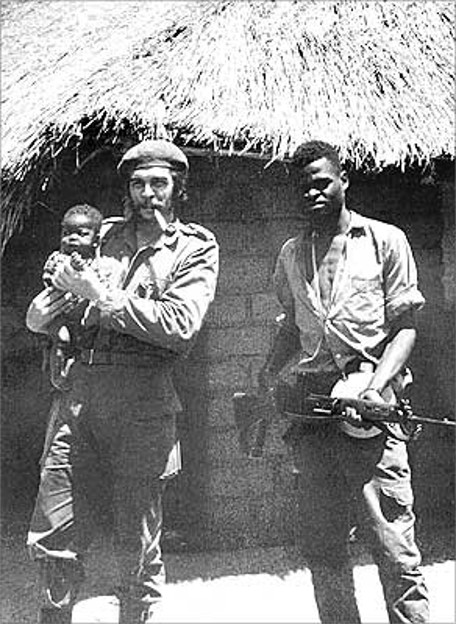

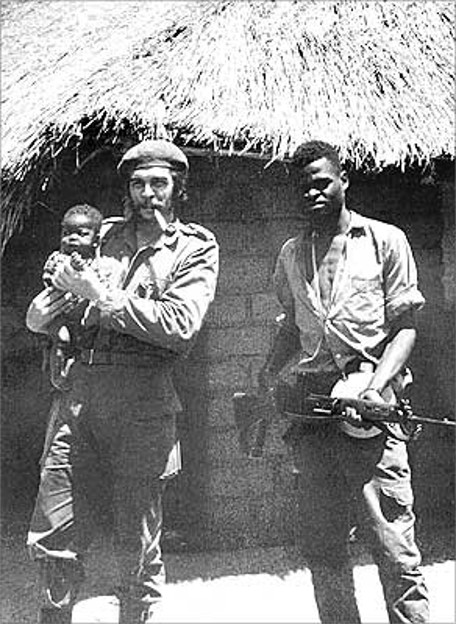

Congo Crisis

Che Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14th May 1928 – 9 October 1967) was an Argentines, Argentine Communist revolution, Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and Military theory, military theorist. A majo ...

was committed to ending American imperialism

U.S. imperialism or American imperialism is the expansion of political, economic, cultural, media, and military influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright mi ...

, and he decided to travel to the Congo during its civil war to back the anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and Political movement, movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. Anti-capitalists seek to combat the worst effects of capitalism and to eventually replace capitalism ...

guerrilla groups. Guevara's aim was to export the revolution by instructing local anti-Mobutu

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga ( ; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997), often shortened to Mobutu Sese Seko or Mobutu and also known by his initials MSS, was a Congolese politician and military officer ...

Simba fighters in Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

ideology and foco

A guerrilla foco is a small cadre of revolutionaries operating in a nation's countryside. This guerrilla organization was popularized by Che Guevara in his book ''Guerrilla Warfare (Che Guevara book), Guerrilla Warfare'', which was based on his e ...

theory strategies of guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

. In his ''Congo Diary'', he cites the incompetence, intransigence and infighting of the local Congolese forces as key reasons for the insurgency's failure. On 20 November 1965, in ill health with dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

, suffering from acute asthma, and disheartened after seven months of frustrations and inactivity, Guevara left the Congo with the Cuban survivors (six members of his 12-man column had died). At one point, Guevara considered sending the wounded back to Cuba, and fighting in Congo alone until his death, as an ideological example. After being urged by his comrades and pressed by two emissaries sent by Castro, at the last moment, Guevara reluctantly agreed to leave Africa. In speaking about his experience in the Congo months later, Guevara concluded that he left rather than fight to the death because: "The human element for the revolution in the Congo had failed. The people have no will to fight. The revolutionary leaders are corrupt. In simple words... there was nothing to do." A few weeks later, when writing the preface to the diary he kept during the Congo venture, he began: "This is the story of a failure."

At a meeting in Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

, Juan PerĂ³n

Juan Domingo PerĂ³n (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine military officer and Statesman (politician), statesman who served as the History of Argentina (1946-1955), 29th president of Argentina from 1946 to RevoluciĂ³n Libertad ...

, who was sympathetic to Guevara but disapproved of Guevara's choice of guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

as antiquated, warned Guevara about starting operations in Bolivia.

Guerrilla operations

Guevara enteredBolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

with the pseudonym "Adolfo Mena GonzĂ¡lez" on 3 November 1966. Three days later, he left the capital city of La Paz

La Paz, officially Nuestra Señora de La Paz (Aymara language, Aymara: Chuqi Yapu ), is the seat of government of the Bolivia, Plurinational State of Bolivia. With 755,732 residents as of 2024, La Paz is the List of Bolivian cities by populati ...

for the countryside. He planned to organize a foco

A guerrilla foco is a small cadre of revolutionaries operating in a nation's countryside. This guerrilla organization was popularized by Che Guevara in his book ''Guerrilla Warfare (Che Guevara book), Guerrilla Warfare'', which was based on his e ...

with Bolivia as his target. Planning to start a guerrilla campaign against the military government of President René Barrientos, he assembled a band of 29 Bolivians, 25 Cubans, and a few foreigners which included Guevara himself, one woman from East Germany named Tamara Bunke, and three Peruvians. This small but well-armed group carried out two successful ambushes against two army patrols in the spring of 1967, but failed to gain significant support from fellow opposition groups in Bolivia's cities or from local civilians, some of whom willingly informed the authorities of the guerrillas' movements.

Barrientos was very concerned with Guevara's rising insurgency, and clamped down on popular protest with some very heavy-handed measures (such as the San Juan massacre

The San Juan massacre is the name given to an attack by the Bolivian military on miners of the Siglo XX- Catavi tin mining complex in Bolivia. The attack occurred on 24 June 1967, in the early hours of the traditional festival of the Night o ...

). Guevara felt that such an atrocity by the Bolivian Army

The Bolivian Army () is the land force branch of the Armed Forces of Bolivia.

Figures on the size and composition of the Bolivian army vary considerably, with little official data available. It is estimated that the army has between 26,000 and 6 ...

and Air Force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

would be the tipping point in his favor in rallying the miners to his guerrilla insurgency, but he did not make contact with the political organization of the miners himself, preferring to negotiate with representatives of the Bolivian Communist Party. He also chose to locate his insurgency far from the locations of strong political organization among workers and indigenous communities.

As part of the operation, Bunke managed to infiltrate Bolivian high society to the point of winning the adoration of President Barrientos and even going on holiday with him to Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

. Bunke used her position to relay intelligence to the guerrillas and act as their contact with the outside world. In late 1966, the unreliability of many of her comrades in the urban network set up to support the guerrillas forced her to travel to their rural camp at Ă‘ancahuazĂº on a number of occasions. On one of these trips, a captured Bolivian communist gave away a safe house where her jeep was parked in which she had left her address book. As a result, her cover was blown, and she had to join Guevara's armed guerrilla campaign. With the loss of their only contact with the outside world, the guerrillas found themselves isolated.

By mid-1967, Guevara's men became fugitives, hunted down by Bolivian special forces

Special forces or special operations forces (SOF) are military units trained to conduct special operations. NATO has defined special operations as "military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, selected, trained and equip ...

and their American advisors. In the last few months of the venture, Guevara wrote in his diary that: "Talking to these peasants is like talking to statues. They do not give us any help. Worse still, many of them are turning into informants." The guerrillas suffered heavy losses in a series of clashes with the Bolivian Army. Constantly on the move and facing shortages of food, medicine, and equipment, Guevara's guerrillas were worn down and several desertions occurred. Units of the Bolivian Army's 4th and 8th Divisions cordoned off the general area where Guevara was operating, gradually encircling the guerrillas. The rough terrain of canyons, rolling hills with deep thorn-infested ravines, and thick vegetation hampered the army's search for the guerrillas, all the while the guerrillas kept moving, trying to find a way to escape from the encirclement.

On 31 August 1967, a small group of the guerrillas, totaling eight men as well as Bunke, were ambushed and killed by Bolivian soldiers as they attempted to cross the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( or ) in the United States or the RĂo Bravo (del Norte) in Mexico (), also known as TĂ³ Ba'Ă¡adi in Navajo language, Navajo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the Southwestern United States a ...

in Bolivia. On 26 September 1967, Guevara's band, which by then had been reduced to 22 guerrillas, entered the village of La Higuera, which they found almost deserted. There, Guevara discovered that the Bolivian authorities knew of his presence in the area when he found a telegram to the village mayor warning of the band's approach. As the guerrillas left the village, they fell into another Bolivian Army ambush and three more were killed. The guerrillas then fled two kilometers west into the rugged canyons of the area. Two more guerrillas deserted during the retreat.

On 8 October 1967, the Bolivian Army's 2nd Ranger Battalion located Guevara's band. Most of the surviving guerrillas were surrounded and destroyed as a fighting force by the Bolivian Army Rangers. The fighting ended with Guevara's capture. Still, some guerrillas remained active across Bolivia during the rest of October and November 1967. Meanwhile, the Bolivian Army continued to hunt down the remaining guerrillas. In fighting that lasted from 8 to 14 October, the Bolivian Army Rangers killed 11 guerrillas for the loss of 9 killed and 4 wounded. Five other guerrillas - Daniel AlarcĂ³n RamĂrez, Leonardo Tamayo NĂºĂ±ez, David Adriazola, Harry Villegas, and Inti Peredo - survived and escaped into Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

.

Guevara's capture and execution

FĂ©lix RodrĂguez, a Cuban exile turned CIA Special Activities Division operative, trained and advised Bolivian troops during the hunt for Guevara in Bolivia. On 7 October, a local informant apprised the Bolivian special forces of the location of Guevara's guerrilla encampment in the Yuro ravine. On 8 October, they encircled the area with 180 soldiers, and Guevara was wounded and taken prisoner while leading a detachment with Simeon Cuba Sarabia by a Bolivian Army Ranger unit commanded by Captain Gary Prado SalmĂ³n. Che biographer Jon Lee Anderson reports Bolivian Sergeant Bernardino Huanca's account: that a twice wounded Guevara, his gun rendered useless, shouted "Do not shoot! I am Che Guevara and worth more to you alive than dead." Guevara was tied up and taken to a dilapidated mud schoolhouse in the nearby village of La Higuera on the night of 8 October. For the next half day, Guevara refused to be interrogated by Bolivian officers and would only speak quietly to Bolivian soldiers. One of those Bolivian soldiers, helicopter pilot Jaime Nino de Guzman, describes Che as looking "dreadful". According to de Guzman, Guevara was shot through the right calf, his hair was matted with dirt, his clothes were shredded, and his feet were covered in rough leather sheaths. Despite his haggard appearance, he recounts that "Che held his head high, looked everyone straight in the eyes and asked only for something to smoke." De Guzman states that he "took pity" and gave him a small bag of tobacco for his pipe, with Guevara then smiling and thanking him.The Man Who Buried Cheby Juan O. Tamayo, ''Miami Herald'', 19 September 1997. Later on the night of 8 October, Guevara, despite having his hands tied, kicked Bolivian Officer Captain Espinosa into the wall, after the officer entered the schoolhouse in order to snatch Guevara's pipe from his mouth as a souvenir. In another instance of defiance, Guevara spat in the face of Bolivian Rear Admiral Ugarteche shortly before his execution. Captain Prado told Guevara that he would be taken to the city of

Santa Cruz de la Sierra

Santa Cruz de la Sierra (; ), commonly known as Santa Cruz, is the largest city in Bolivia and the capital of the Santa Cruz Department (Bolivia), Santa Cruz department.

Situated on the Pirai River (Bolivia), Pirai River in the eastern Tropical ...

and court-martialed there.

The following morning on 9 October, Guevara asked to see the ''"maestra"'' (school teacher) of the village, 22-year-old Julia Cortez. Cortez would later state that she found Guevara to be an "agreeable looking man with a soft and ironic glance" and that during their short conversation she found herself "unable to look him in the eye", because his "gaze was unbearable, piercing, and so tranquil." During their short conversation, Guevara pointed out to Cortez the poor condition of the schoolhouse, stating that it was "anti-pedagogical

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political, and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken ...

" to expect campesino students to be educated there, while "government officials drive Mercedes cars" ... declaring "that's what we are fighting against."

Later that morning on 9 October, President Barrientos ordered that Guevara be killed. The order was relayed to RodrĂguez, who in turn informed the commander of the Bolivian Army's 8th Division, Colonel Joaquin Zenteno Anaya. The US government wanted Guevara to be taken to Panama for interrogation and the CIA had placed aircraft on standby for such a transfer. RodrĂguez had been told to keep Guevara alive. He asked Anaya to allow Guevara to be taken into CIA custody in Panama, but Anaya insisted that the order to execute him be carried out. The executioner was Mario TerĂ¡n, a young sergeant

Sergeant (Sgt) is a Military rank, rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and in other units that draw their heritage f ...

in the Bolivian Army who had requested to shoot Che on the basis of the fact that three of his friends from B Company, all named "Mario", had been killed in an earlier firefight with Guevara's band of guerrillas. Taibo 1999, p. 267. To make the bullet wounds appear consistent with the story the government planned to release to the public, RodrĂguez told TerĂ¡n not to shoot Guevara in the head, but to aim carefully to make it appear that Guevara had been killed in action during a clash with the Bolivian army. Captain Prado said that the possible reasons Barrientos ordered the immediate execution of Guevara is so there would be no possibility that Guevara would escape from prison, and also so there would be no drama in regard to a trial.

Before Guevara was executed he was asked by a Bolivian soldier if he was thinking about his own immortality. "No", he replied, "I'm thinking about the immortality of the revolution." A few minutes later, Sergeant TerĂ¡n entered the hut and ordered the other soldiers out. Alone with TerĂ¡n, Che Guevara then stood up and spoke to his executioner: "I know you've come to kill me." TerĂ¡n pointed his M2 carbine at Guevara, but hesitated in which Guevara spat at TerĂ¡n which were his last words: "Shoot, coward! You are only going to kill a man!" Anderson 1997, p. 739. TerĂ¡n then opened fire, hitting Guevara in the arms and legs. For a few seconds, Guevara writhed on the ground, apparently biting one of his wrists to avoid crying out. TerĂ¡n then fired several times again, wounding him fatally in the chest at 1:10 pm, according to RodrĂguez. In all, Guevara was shot by TerĂ¡n nine times. This included five times in the legs, once in the right shoulder and arm, once in the chest, and finally in the throat.

Months earlier, during his last public declaration to the Tricontinental Conference,Message to the TricontinentalA letter sent by Che Guevara from his jungle camp in Bolivia, to the Tricontinental Solidarity Organisation in Havana, Cuba, in the Spring of 1967. Guevara wrote his own

epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

, stating "Wherever death may surprise us, let it be welcome, provided that this our battle cry may have reached some receptive ear and another hand may be extended to wield our weapons."

Aftermath

After he was killed, Guevara's body was lashed to the landing skids of a helicopter and flown to nearby Vallegrande, where photographs were taken of him lying on a concrete slab in the laundry room of the Nuestra Señora de Malta. As hundreds of local residents filed past the body, many of them considered Guevara's corpse to represent a "Christ-like" visage, with some of them even surreptitiously clipping locks of his hair as divine relics. Such comparisons were further extended when two weeks later upon seeing the post-mortem photographs, English art criticJohn Berger

John Peter Berger ( ; 5 November 1926 – 2 January 2017) was an English art critic, novelist, painter and poet. His novel '' G.'' won the 1972 Booker Prize, and his essay on art criticism '' Ways of Seeing'', written as an accompaniment to t ...

observed that they resembled two famous paintings: Rembrandt

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (; ; 15 July 1606 – 4 October 1669), mononymously known as Rembrandt was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker, and Drawing, draughtsman. He is generally considered one of the greatest visual artists in ...

's ''The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

''The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp'' is a 1632 oil painting on canvas by Rembrandt housed in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, the Netherlands. It was originally created to be displayed by the Surgeons Guild in their meeting room. The p ...

'' and Andrea Mantegna

Andrea Mantegna (, ; ; September 13, 1506) was an Italian Renaissance painter, a student of Ancient Rome, Roman archeology, and son-in-law of Jacopo Bellini.

Like other artists of the time, Mantegna experimented with Perspective (graphical), pe ...

's '' Lamentation over the Dead Christ''. There were also four correspondents present when Guevara's body arrived in Vallegrande, including Bjorn Kumm of the Swedish ''Aftonbladet

(, lit. "The evening paper") is a Swedish language, Swedish daily tabloid newspaper published in Stockholm, Sweden. It is one of the largest daily newspapers in the Nordic countries.

History and profile

The newspaper was founded by Lar ...

'', who described the scene in a 11 November 1967, exclusive for ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' (often abbreviated as ''TNR'') is an American magazine focused on domestic politics, news, culture, and the arts from a left-wing perspective. It publishes ten print magazines a year and a daily online platform. ''The New Y ...

''.

Bolivia had defeated its last major insurgency to date. President Barrientos himself died in a helicopter crash on 27 April 1969. Most of Guevara's men were killed, wounded, or captured in the campaign.

On 17 February 1968, five surviving guerrillas, three Cubans and two Bolivians, managed to get to Chile. There they were detained by policing carabiniers and sent to Iquique

Iquique () is a port List of cities in Chile, city and Communes of Chile, commune in northern Chile, capital of both the Iquique Province and TarapacĂ¡ Region. It lies on the Pacific coast, west of the Pampa del Tamarugal, which is part of the At ...

. On 22 February, the guerrillas applied for asylum. While in Iquique they were visited by Salvador Allende

Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens (26 June 1908 – 11 September 1973) was a Chilean socialist politician who served as the 28th president of Chile from 1970 until Death of Salvador Allende, his death in 1973 Chilean coup d'état, 1973. As a ...

, then president of the senate of Chile

The president of the Senate of Chile is the presiding officer of the Senate of Chile. The position comes after the Ministers of State in the line of succession of the President of Chile in case of temporary incapacitation or vacancy, according t ...

. After the guerrilla's meeting with Allende and other prominent leftist politicians, the interior minister of the Christian Democrat

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian ethics#Politics, Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo ...

government Edmundo PĂ©rez Zujovic decided to expel the guerrillas from Chile. Due to problems in obtaining transit visas the journey to Cuba was done via Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

.. ''Punto Final''. 16 May 2008.

1970 Chilean presidential election

Presidential elections were held in Chile on 4 September 1970. Salvador Allende of the Popular Unity (Chile), Popular Unity alliance won a narrow Plurality (voting), plurality in a race against independent Jorge Alessandri and Christian Democra ...

. By the time of the election, the bodyguard had expanded with the addition of more ex-Ă‘ancahuazĂº Guerrillas volunteering to provide security to Allende and, later, members of the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR). On one of Allende's first public appearances after his inauguration, a Chilean journalist inquired of the president who the armed men were accompanying him, to which Allende replied "a group of personal friends", giving the group the moniker from which it would thereafter be known.

On 11 May 1976, Joaquin Zenteno Anaya, a career officer who was the person in charge of the Bolivian military region of Santa Cruz when Guevara captured and executed there, was shot dead in broad daylight underneath a subway bridge over the Seine River

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres p ...

in Paris, France

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. At the time of his assassination, Anaya was Bolivia's Ambassador to France. In a phone call to Agence France-Presse

Agence France-Presse (; AFP) is a French international news agency headquartered in Paris, France. Founded in 1835 as Havas, it is the world's oldest news agency.

With 2,400 employees of 100 nationalities, AFP has an editorial presence in 260 c ...

, an unidentified person said the "International Che GueVara Brigades" claimed responsibility for the slaying.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ă‘ancahuazĂº Guerrilla History of South America Wars involving Bolivia Wars involving Cuba 1960s in Bolivia 20th-century rebellions Military assassinations Guerrilla wars Che Guevara Conflicts in 1967 Communism in Bolivia Communist rebellions Proxy wars Rebellions in Bolivia