Æthelberht II Of East Anglia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Æthelberht (

Æthelberht (

Little is known of Æthelberht's life or reign, as few

Little is known of Æthelberht's life or reign, as few

''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' (Ethelbert)

/ref> Four pennies minted by Æthelberht are known ()—two of which have been known since the 18th century, and one since the beginning of the 20th century. One of these, a 'light' penny, said to have been discovered in 1908 at Tivoli, near Rome, is similar in type to the coinage of Offa. On one side is the word ''REX'', with an image of

After his death, Æthelberht was

After his death, Æthelberht was

The Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Ethelbert are joint patrons of Hereford Cathedral, where the music for the ''Office of St Ethelbert'' survives in the 13th century ''Hereford Noted

The Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Ethelbert are joint patrons of Hereford Cathedral, where the music for the ''Office of St Ethelbert'' survives in the 13th century ''Hereford Noted

Facsimile of the manuscript of ''Passio sancti athelberhti''

in the

''Two Lives of St. Ethelbert''

by

Æthelberht (

Æthelberht (Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

: ''Æðelbrihte'', ''ÆÞelberhte''), also called Saint Ethelbert the King (died 20 May 794 at Sutton Walls, Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouthshire ...

), was an eighth-century saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Ĺ , holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

and a king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

of East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

, the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

kingdom which today includes the English counties of Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

and Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

. Little is known of his reign, which may have begun in 779, according to later sources, and very few of the coins he issued have been discovered. It is known from the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alf ...

'' that he was killed on the orders of Offa of Mercia

Offa (died 29 July 796 AD) was List of monarchs of Mercia, King of Mercia, a kingdom of History of Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa of Mercia, Eowa, Offa came to ...

in 794.

Æthelberht was locally canonised

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of ...

and became the focus of cults

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. This ...

in East Anglia and at Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. With a population ...

, where the shrine of the saintly king once existed. In the absence of known historical facts, mediaeval chroniclers

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and lo ...

provided their own details for his ancestry, life as king, and death at the hands of Offa. His feast day is 20 May. There are churches in Norfolk, Suffolk and the west of England dedicated to him, and he is a joint patron

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

of Hereford Cathedral

Hereford Cathedral is the cathedral church of the Anglican Diocese of Hereford in Hereford, England.

A place of worship has existed on the site of the present building since the 8th century or earlier. The present building was begun in 1079. S ...

.

Life and reign

Little is known of Æthelberht's life or reign, as few

Little is known of Æthelberht's life or reign, as few East Anglian

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

records have survived from this period. Æthelberht's reign may have begun in 779, the date provided on the uncertain authority of a much later saint's life. Mediaeval chroniclers

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and lo ...

have provided dubious accounts of his life, in the absence of any real details. According to Richard of Cirencester

Richard of Cirencester ( la, Ricardus de Cirencestria; before 1340–1400) was a cleric and minor historian of the Benedictine abbey at Westminster. He was highly famed in the 18th and 19th century as the author of '' The Description of Britain'' b ...

, writing in the 15th century, Æthelberht's parents were Æthelred I of East Anglia and Leofrana of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ye ...

. Richard narrates in detail a story of Æthelberht's piety, election as king and wise rule. Urged to marry against his will, he apparently agreed to wed Eadburh

Eadburh ( ang, Ä’adburh), also spelled Eadburg, ( fl. 787–802) was the daughter of King Offa of Mercia and Queen Cynethryth. She was the wife of King Beorhtric of Wessex, and according to Asser's ''Life of Alfred the Great'' she killed h ...

, the daughter of Offa of Mercia

Offa (died 29 July 796 AD) was List of monarchs of Mercia, King of Mercia, a kingdom of History of Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa of Mercia, Eowa, Offa came to ...

, and set out to visit her, despite his mother's forebodings and his experiences of terrifying events—an earthquake, a solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six month ...

and a vision.Internet Archive â€''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' (Ethelbert)

/ref> Four pennies minted by Æthelberht are known ()—two of which have been known since the 18th century, and one since the beginning of the 20th century. One of these, a 'light' penny, said to have been discovered in 1908 at Tivoli, near Rome, is similar in type to the coinage of Offa. On one side is the word ''REX'', with an image of

Romulus

Romulus () was the legendary foundation of Rome, founder and King of Rome, first king of Ancient Rome, Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus ...

and Remus suckling a wolf: the obverse names the king and his moneyer, Lul, who also struck coins for Offa and Coenwulf of Mercia

Coenwulf (; also spelled Cenwulf, Kenulf, or Kenwulph; la, Coenulfus) was the King of Mercia from December 796 until his death in 821. He was a descendant of King Pybba, who ruled Mercia in the early 7th century. He succeeded Ecgfrith, the son ...

. The author Andy Hutcheson has suggested that the use of runes on the coin may signify "continuing strong control by local leaders". The numismatist

A numismatist is a specialist in numismatics ("of coins"; from Late Latin ''numismatis'', genitive of ''numisma''). Numismatists include collectors, specialist dealers, and scholars who use coins and other currency in object-based research. Altho ...

Marion Archibald

Marion MacCallum Archibald (1935 – 23 April 2016) was a British numismatist, author and for 33-years a curator at the British Museum. She was the first woman to be appointed Assistant Keeper in the Department of Coins and Medals and is regarde ...

notes that the issuing of "flattering" coins of this type, with the intention to win friends in Rome, probably indicated that as a sub-king, Æthelberht was assuming "a greater degree of independence than ffawas prepared to tolerate".

The coins provide one of the few contemporary sources for Æthelberht. In March 2014 the fourth coin was discovered in Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

by a metal detector

A metal detector is an instrument that detects the nearby presence of metal. Metal detectors are useful for finding metal objects on the surface, underground, and under water. The unit itself, consist of a control box, and an adjustable shaft, ...

ist. According to the British numismatist Rory Naismith, "Æthelberht’s coins could have been issued over a number of years, either during a spell when some or all of East Anglia asserted independence from Offa, or by some sort of arrangement to share minting rights

From the Middle Ages to the Early modern period (or even later), to have minting rights was to have "the power to mint coins and to control currency within one's own dominion."

History

In the Middle Ages there were at times a large number of mi ...

with the Mercian ruler." Offa stopped Æthelberht from minting his own coins.

In 793 the vulnerability of the English east coast was exposed when the monastery at Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th century AD; it was an important ...

was looted by Vikings

Vikings ; non, vĂkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

, and a year later Jarrow

Jarrow ( or ) is a town in South Tyneside in the county of Tyne and Wear, England. It is east of Newcastle upon Tyne. It is situated on the south bank of the River Tyne, about from the east coast. It is home to the southern portal of the Tyne ...

was also attacked, which the historian Steven Plunkett reasons would ensure that the East Anglians were "forced to seek firm leadership" in order to strengthen the region's defences. Æthelberht's claim to belong to the ruling Wuffingas

The Wuffingas, Uffingas or Wiffings were the ruling dynasty of East Anglia, the long-lived Anglo-Saxon kingdom which today includes the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. The Wuffingas took their name from Wuffa, an early East Anglian king ...

dynasty, suggested by the use of a Roman she-wolf and the title ''REX'' on his coins, arose from the need for strong kingship in response to the Viking attacks.

Death and canonisation

Æthelberht was put to death by Offa under unclear circumstances, apparently at theroyal vill

A royal vill, royal ''tun'' or ''villa regalis'' ( ang, cyneliċ tūn) was the central settlement of a rural territory in Anglo Saxon England, which would be visited by the King and members of the royal household on regular circuits of their kingd ...

at Sutton Walls. According to the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alf ...

'', he was beheaded

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the ...

. Mediaeval sources tell how he was captured while visiting his future bride Ælfthyth and was then murdered and buried. In Richard of Cirencester's account, which cannot be substantiated, Offa's evil queen Cynethryth

Cynethryth (''CyneĂ°ryĂ°''; died after AD 798) was a Queen of Mercia, wife of King Offa of Mercia and mother of King Ecgfrith of Mercia. Cynethryth is the only Anglo-Saxon queen consort in whose name coinage was definitely issued.

Biography Ori ...

persuaded her husband to kill his guest, who was then bound and beheaded by a certain Grimbert, and his body disposed of. The mediaeval historian John Brompton

John Brompton or Bromton ( fl. 1436) was a supposed English chronicler.

Brompton was elected abbot of Jervaulx in 1436. The authorship of the compilation printed in Roger Twysden's ''Decem Scriptores'' Col. 725-1284, Lond. 1652; with the title ' ...

's ''Chronicon'' describes how the king's detached head fell off a cart into a ditch where it was found, before it restored a blind man's sight. According to the ''Chronicon'', Ælfthyth became a recluse at Crowland

Crowland (modern usage) or Croyland (medieval era name and the one still in ecclesiastical use; cf. la, Croilandia) is a town in the South Holland district of Lincolnshire, England. It is situated between Peterborough and Spalding. Crowland c ...

and her remorseful father founded monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

, gave land to the Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

and travelled on a pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

to Rome.

The execution of an Anglo-Saxon king on the orders of another ruler was very rare, although criminals were hanged and beheaded, as has been discovered at Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo is the site of two early medieval cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near the English town of Woodbridge. Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when a previously undisturbed ship burial containing a ...

. Æthelberht's death made the possibility of any peaceful union between the Anglian peoples, including Mercia, less likely than before.

In 2014, metal-detectorist Darrin Simpson found a coin minted by Æthelbert in a Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

field. Such coins, struck as a sign of independence, may have led to Æthelbert's death. It sold at auction on 11 June 2014 for £78,000.

Legacy

Veneration

After his death, Æthelberht was

After his death, Æthelberht was canonised

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of ...

by the English Church. A number of ''Lives

Lives may refer to:

* The plural form of a ''life''

* Lives, Iran, a village in Khuzestan Province, Iran

* The number of lives in a video game

* '' Parallel Lives'', aka ''Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans'', a series of biographies of famous m ...

'' of St Æthelberht were written during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, including those by Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales ( la, Giraldus Cambrensis; cy, Gerallt Gymro; french: Gerald de Barri; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and English historians in the Middle Ages, historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and w ...

and Osbert of Clare

Osbert of Clare (died in or after 1158) was a monk, elected prior of Westminster Abbey and briefly abbot. He was a prolific writer of letters, a hagiographer and a forger of charters.

Life

Osbert was born towards the end of the eleventh century a ...

in the 12th century, and hagiographies by Roger of Wendover

Roger of Wendover (died 6 May 1236), probably a native of Wendover in Buckinghamshire, was an English chronicler of the 13th century.

At an uncertain date he became a monk at St Albans Abbey; afterwards he was appointed prior of the cell of ...

and Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris ( la, Matthæus Parisiensis, lit=Matthew the Parisian; c. 1200 – 1259), was an English Benedictine monk, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey ...

the following century.

He was venerated in religious cults in both East Anglia and at Hereford. The Anglo-Saxon church of the episcopal estate at Hoxne

Hoxne ( ) is a village in the Mid Suffolk district of Suffolk, England, about five miles (8 km) east-southeast of Diss, Norfolk and south of the River Waveney. The parish is irregularly shaped, covering the villages of Hoxne, Cross Street a ...

was one of several dedicated to him in Suffolk. The church is mentioned in the will of Theodreusus, Bishop of London and Hoxne (c. 938 – c. 951), which is a possible indication of the existence of a religious cult

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. This s ...

devoted to the saintly king. Only three dedications for Æthelberht are near where he died – Marden, Hereford Cathedral

Hereford Cathedral is the cathedral church of the Anglican Diocese of Hereford in Hereford, England.

A place of worship has existed on the site of the present building since the 8th century or earlier. The present building was begun in 1079. S ...

and Littledean

Littledean is a village in the Forest of Dean, west Gloucestershire, England. The village has a long history and formerly had the status of a town. Littledean Hall was originally a Saxon hall, although it has been rebuilt and the current house d ...

– the other eleven being in Norfolk or Suffolk. The historian Lawrence Butler has argued that this unusual pattern may be explained by the existence of a royal cult in East Anglia, which represented a "revival of Christianity after the Danish settlement by commemorating a politically 'safe' and corporeally distant local ruler".

Christian buildings dedicated to Æthelberht

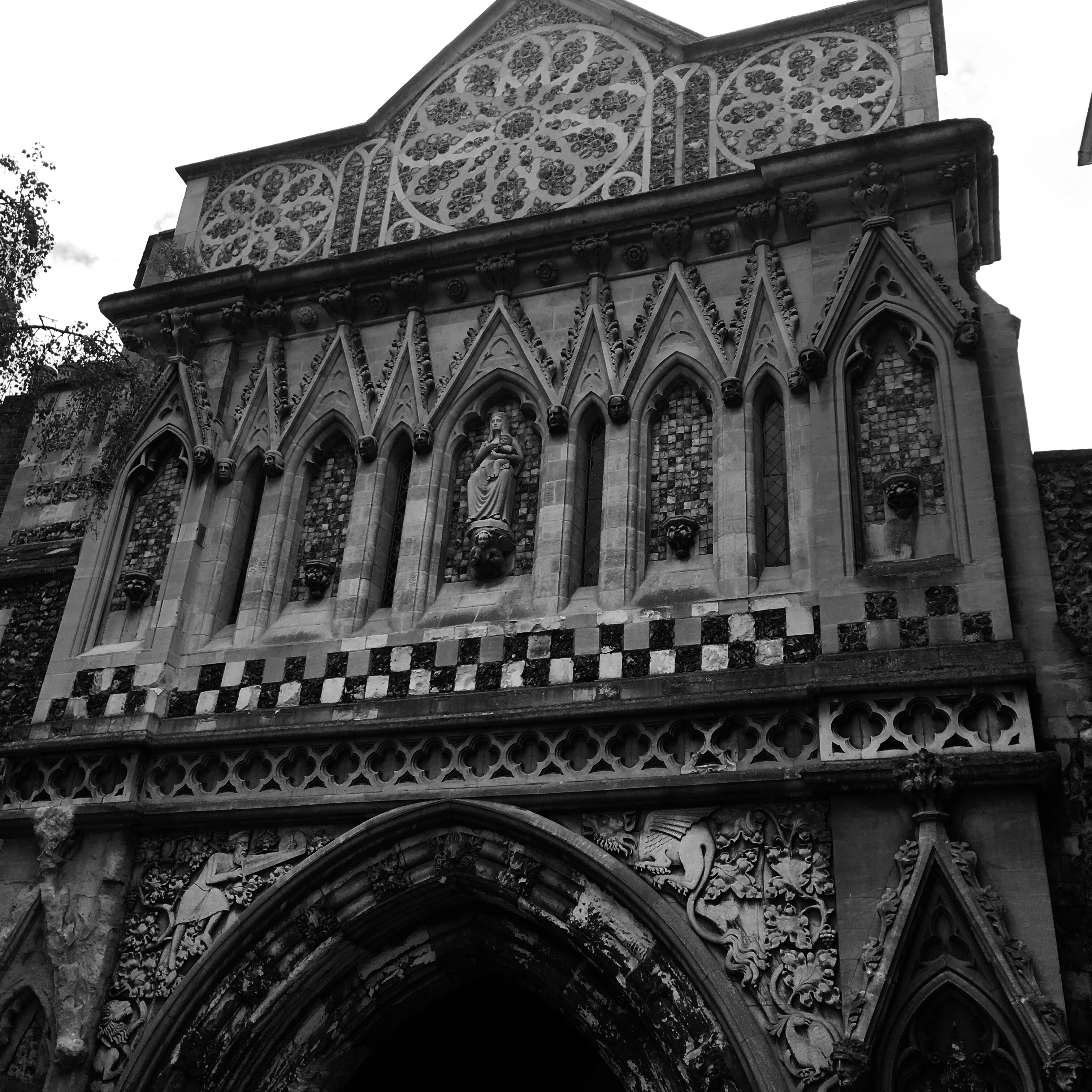

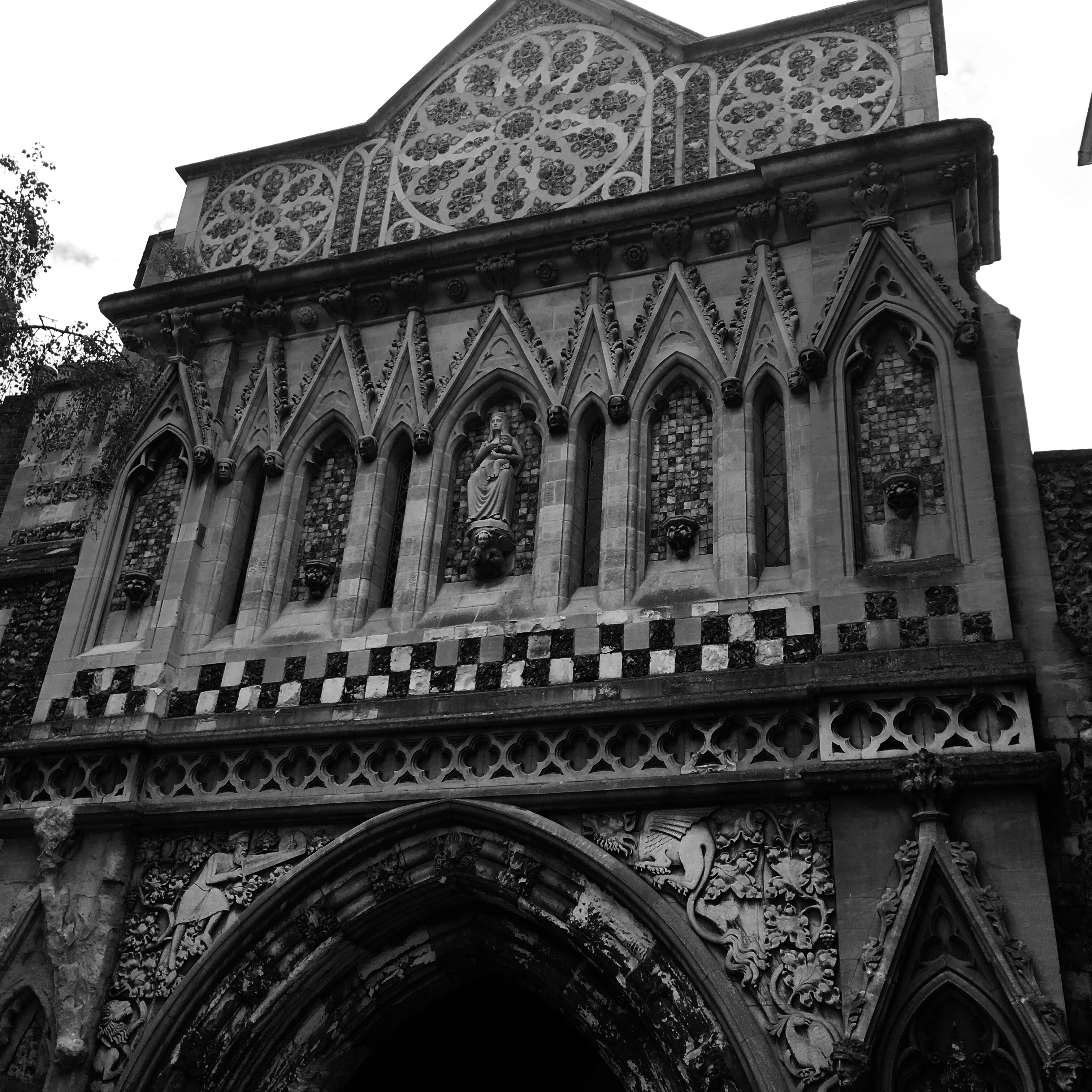

The Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Ethelbert are joint patrons of Hereford Cathedral, where the music for the ''Office of St Ethelbert'' survives in the 13th century ''Hereford Noted

The Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Ethelbert are joint patrons of Hereford Cathedral, where the music for the ''Office of St Ethelbert'' survives in the 13th century ''Hereford Noted Breviary

A breviary (Latin: ''breviarium'') is a liturgical book used in Christianity for praying the canonical hours, usually recited at seven fixed prayer times.

Historically, different breviaries were used in the various parts of Christendom, such a ...

''.

St. Ethelbert's Gate is one of the two main entrances to the precinct of Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Norwich, Norfolk, dedicated to the Holy and Undivided Trinity. It is the cathedral church for the Church of England Diocese of Norwich and is one of the Norwich 12 heritage sites.

The cathedral ...

. The chapel at ''Albrightestone'', at a location near an important excavated Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Boss Hall in Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

, was dedicated to Æthelberht. In Wiltshire, the Church of England parish church

A parish church in the Church of England is the church which acts as the religious centre for the people within each Church of England parish (the smallest and most basic Church of England administrative unit; since the 19th century sometimes ca ...

at Luckington

Luckington is a village and civil parish in the southern Cotswolds, in north-west Wiltshire, England, about west of Malmesbury. The village is on the B4040 road linking Malmesbury and Old Sodbury. The parish is on the county border with Glouces ...

is dedicated to St Mary and St Ethelbert. In Norfolk, the Church of England parish churches at Alby, East Wretham

Wretham is a civil parish in the Breckland district of Norfolk, England. The parish includes the village of East Wretham, which is about northeast of Thetford and southwest of Norwich. It also includes the villages of Illington and Stonebri ...

, Larling, Thurton

Thurton is a village in South Norfolk lying 8½ miles (13½ km) south-east of Norwich on the A146 Norwich to Lowestoft road between Framingham Pigot and Loddon. The A146 effectively divides the village in two; a 40 mph limit is in force. At ...

, Mundham and Burnham Sutton (where there are remains of the ruined church) and the Suffolk churches at Falkenham

Falkenham is a village and a civil parish in the East Suffolk district, in the English county of Suffolk, near the village of Kirton and the towns of Ipswich and Felixstowe. The population of the civil parish as of the 2011 census was 170.

De ...

, Hessett, Herringswell

Herringswell is a village and civil parish in the West Suffolk district of Suffolk in eastern England. In 2005 it had a population of 190. In 2007 there were 128 voters there.McNeill, Phil.Shrine of the times" ''The Telegraph''. 22 July 2007. R ...

and Tannington

Tannington is a village and civil parish in the Mid Suffolk district of Suffolk in eastern England. Located around ten miles south-east of Diss, Norfolk, Diss, in 2005 its population was 110. At the 2011 Census the population had fallen below 100 ...

are all dedicated to the saint. In neighbouring Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

, the parish church at Belchamp Otten

Belchamp Otten is a village and civil parish in Essex, England. It is located approximately west of Sudbury, Suffolk and is north-northeast from the county town of Chelmsford. It is near Belchamp St Paul

Belchamp St Paul is a village and c ...

is dedicated to St Ethelbert and All Saints, and the church at Stanway, originally an Anglo-Saxon chapel, is dedicated to St Albright, which is believed to be the same saint. In 1937, St Ethelbert's name was added to the parish church of St George in East Ham

East Ham is a district of the London Borough of Newham, England, 8 miles (12.8 km) east of Charing Cross. East Ham is identified in the London Plan as a Major Centre. The population is 76,186.

It was originally part of the Becontree Hun ...

, Essex (now London), at the behest of Hereford Cathedral which had funded the rebuilding of the church, previously a temporary wooden structure.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*Facsimile of the manuscript of ''Passio sancti athelberhti''

in the

Parker Library, Corpus Christi College

The Parker Library is a library within Corpus Christi College, Cambridge which contains rare books and manuscripts. It is known throughout the world due to its invaluable collection of over 600 manuscripts, particularly medieval texts, the ...

''Two Lives of St. Ethelbert''

by

M.R. James

Montague Rhodes James (1 August 1862 – 12 June 1936) was an English author, medievalist scholar and provost of King's College, Cambridge (1905–1918), and of Eton College (1918–1936). He was Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambrid ...

, which was published in ''English Historical Review'', volume 32 (1917), from the Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Aethelberht 02 Of East Anglia

8th-century Christian saints

794 deaths

East Anglian monarchs

East Anglian saints

Burials at Hereford Cathedral

8th-century Christian martyrs

8th-century English monarchs

Christian royal saints

Year of birth unknown