|

Zero-marking Language

A zero-marking language is one with no grammatical marks on the dependents or the modifiers or the heads or nuclei that show the relationship between different constituents of a phrase. Pervasive zero marking is very rare, but instances of zero marking in various forms occur in quite a number of languages. Vietnamese and Indonesian are two national languages listed in the World Atlas of Language Structures as having zero-marking. In many East and Southeast Asian languages, such as Thai and Chinese, the head verb and its dependents are not marked for any arguments or for the nouns' roles in the sentence. On the other hand, possession is marked in such languages by the use of clitic particles between possessor and possessed. Some languages, such as many dialects of Arabic, use a similar process, called juxtaposition, to indicate possessive relationships. In Arabic, two nouns next to each other could indicate a possessed-possessor construction: ' "Maryam's books" (liter ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Marker (linguistics)

In linguistics, a marker is a free or bound morpheme that indicates the grammatical function of the marked word, phrase, or sentence. Most characteristically, markers occur as clitics or inflectional affixes. In analytic languages and agglutinative languages, markers are generally easily distinguished. In fusional languages and polysynthetic languages, this is often not the case. For example, in Latin, a highly fusional language, the word '' amō'' ("I love") is marked by suffix '' -ō'' for indicative mood, active voice, first person, singular, present tense. Analytic languages tend to have a relatively limited number of markers. Markers should be distinguished from the linguistic concept of markedness. An ''unmarked'' form is the basic "neutral" form of a word, typically used as its dictionary lemma, such as—in English—for nouns the singular (e.g. ''cat'' versus ''cats''), and for verbs the infinitive (e.g. ''to eat'' versus ''eats'', ''ate'' and ''eaten''). Unmarked forms ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic ( ar, links=no, ٱلْعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ, al-ʿarabīyah al-fuṣḥā) or Quranic Arabic is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad and Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, elevated prose and oratory, and is also the liturgical language of Islam. The first comprehensive description of ''Al-ʿArabiyyah'' "Arabic", Sibawayh's ''al''-''Kitāb'', was upon a corpus of poetic texts, in addition to the Qurʾān and Bedouin informants whom he considered to be reliable speakers of the ''ʿarabiyya''. Modern Standard Arabic is its direct descendant used today throughout the Arab world in writing and in formal speaking, for example prepared speeches, some radio and TV broadcasts and non-entertainment content. Whilst the lexis and stylistics of Modern Standard Arabic are different from Classical Arabic, the morphology and syntax have remained basically unchang ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Zero-marking In English

Zero-marking in English is the indication of a particular grammatical function by the absence of any morpheme (word, prefix, or suffix). The most common types of zero-marking in English involve English articles#General usage, zero articles, English relative clauses#Zero relative pronoun, zero relative pronouns, and zero subordinating conjunctions. Examples are ''I like cats'' in which the absence of the definite article, ''the'', signals ''cats'' to be an indefinite reference, whose specific identity is not known to the listener; ''that's the cat I saw'' in which the relative clause ''(that) I saw'' omits the implied relative pronoun, ''that'', which would otherwise be the object of the clause's verb; and ''I wish you were here''. in which the dependent clause, ''(that) you were here'', omits the subordinating conjunction, ''that''. In some variety (linguistics), varieties of English language, English, grammatical information that would be typically expressed in other English varieti ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Head-marking Language

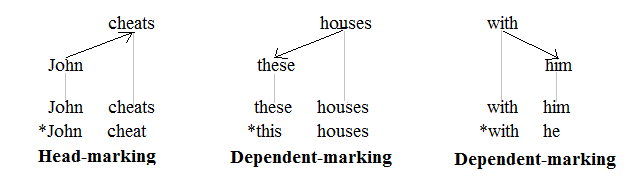

A language is head-marking if the grammatical marks showing agreement between different words of a phrase tend to be placed on the heads (or nuclei) of phrases, rather than on the modifiers or dependents. Many languages employ both head-marking and dependent-marking, and some languages double up and are thus double-marking. The concept of head/dependent-marking was proposed by Johanna Nichols in 1986 and has come to be widely used as a basic category in linguistic typology. In English The concepts of head-marking and dependent-marking are commonly applied to languages that have richer inflectional morphology than English. There are, however, a few types of agreement in English that can be used to illustrate these notions. The following graphic representations of a clause, a noun phrase, and a prepositional phrase involve agreement. The three tree structures shown are those of a dependency grammar (as opposed to those of a phrase structure grammar): :: Heads and dependents ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Double-marking Language

A double-marking language is one in which the grammatical marks showing relations between different constituents of a phrase tend to be placed on both the heads (or nuclei) of the phrase in question, and on the modifiers or dependents. Pervasive double-marking is rather rare, but instances of double-marking occur in many languages. For example, in Turkish, in a genitive construction involving two definite nouns, both the possessor and the possessed are marked, the former with a suffix marking the possessor (and corresponding to a possessive adjective in English) and the latter in the genitive case. For example, 'brother' is ''kardeş,'' and 'dog' is ''köpek,'' but 'brother's dog' is ''kardeşin köpeği.'' (The consonant change is part of a regular consonant lenition.) Another example is a language in which endings that mark gender or case are used to indicate the role of both nouns and their associated modifiers (such as adjectives) in a sentence (such as Russian and Spanish ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Dependent-marking Language

A dependent-marking language has grammatical markers of agreement and case government between the words of phrases that tend to appear more on dependents than on heads. The distinction between head-marking and dependent-marking was first explored by Johanna Nichols in 1986, and has since become a central criterion in language typology in which languages are classified according to whether they are more head-marking or dependent-marking. Many languages employ both head and dependent-marking, but some employ double-marking, and yet others employ zero-marking. However, it is not clear that the head of a clause has anything to do with the head of a noun phrase, or even what the head of a clause is. In English English has few inflectional markers of agreement and so can be construed as zero-marking much of the time. Dependent-marking, however, occurs when a singular or plural noun demands the singular or plural form of the demonstrative determiner ''this/these'' or ''that/those'' and ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Analytic Language

In linguistic typology, an analytic language is a language that conveys relationships between words in sentences primarily by way of ''helper'' words (particles, prepositions, etc.) and word order, as opposed to using inflections (changing the form of a word to convey its role in the sentence). For example, the English-language phrase "The cat chases the ball" conveys the fact that the cat is acting on the ball ''analytically'' via word order. This can be contrasted to synthetic languages, which rely heavily on inflections to convey word relationships (e.g., the phrases "The cat chase''s'' the ball" and "The cat chase''d'' the ball" convey different time frames via changing the form of the word ''chase''). Most languages are not purely analytic, but many rely primarily on analytic syntax. Typically, analytic languages have a low morpheme-per- word ratio, especially with respect to inflectional morphemes. A grammatical construction can similarly be ''analytic'' if it uses un ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

V2 Word Order

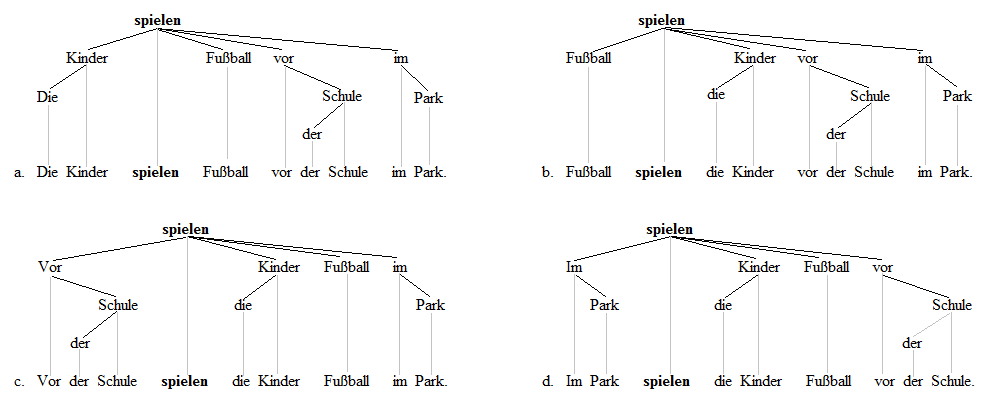

In syntax, verb-second (V2) word order is a sentence structure in which the finite verb of a sentence or a clause is placed in the clause's second position, so that the verb is preceded by a single word or group of words (a single constituent). Examples of V2 in English include (brackets indicating a single constituent): * "Neither do I", " ever in my lifehave I seen such things" If English used V2 in all situations, the following would be correct: * " *n schoollearned I about animals", " * hen she comes home from worktakes she a nap" V2 word order is common in the Germanic languages and is also found in Northeast Caucasian Ingush, Uto-Aztecan O'odham, and fragmentarily in Romance Sursilvan (a Rhaeto-Romansh variety) and Finno-Ugric Estonian. Of the Germanic family, English is exceptional in having predominantly SVO order instead of V2, although there are vestiges of the V2 phenomenon. Most Germanic languages do not normally use V2 order in embedded clauses, with a few ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |