|

Replicon (genetics)

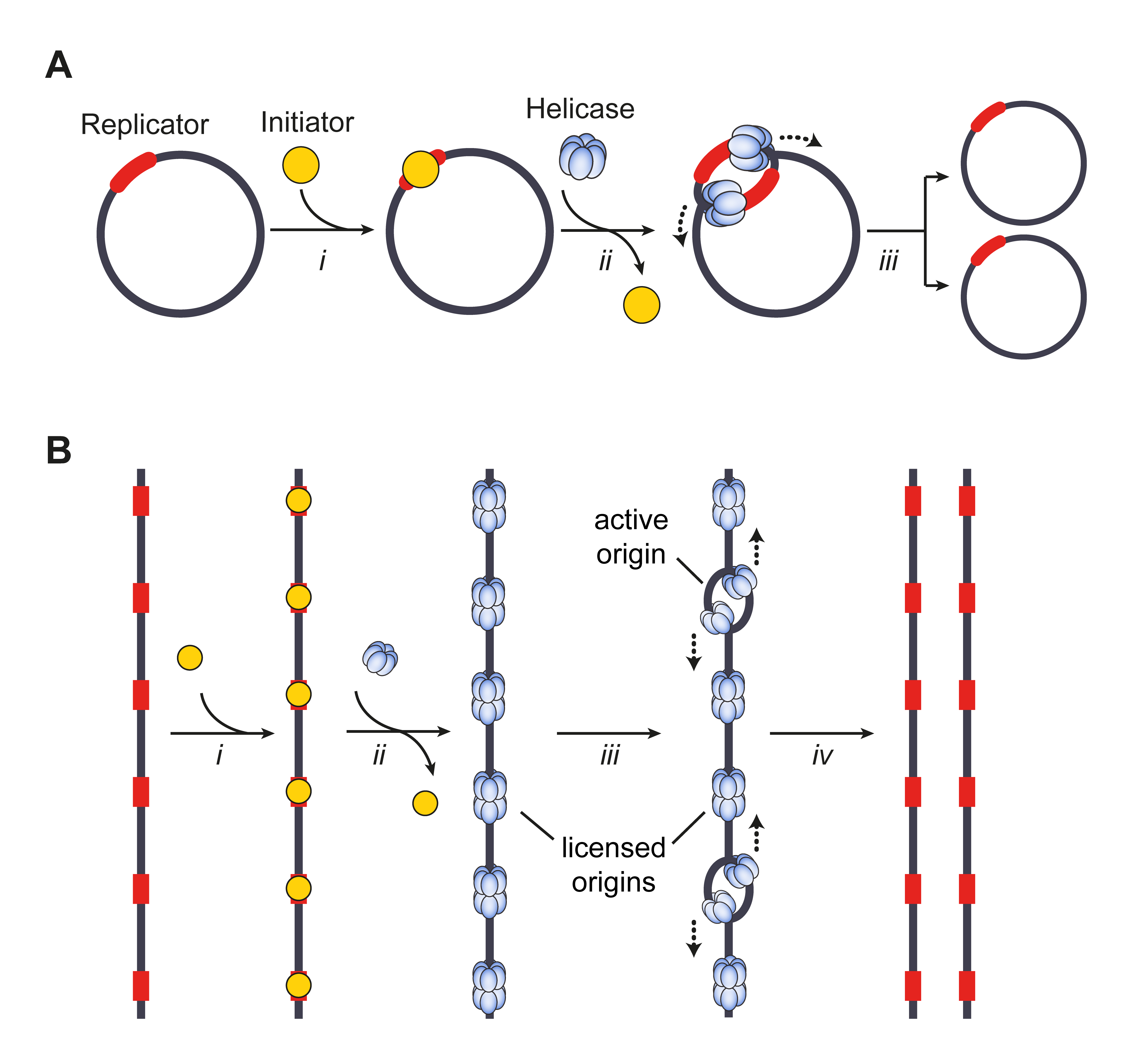

A replicon is a region of an organism's genome that is independently replicated from a single origin of replication. A bacterial chromosome contains a single origin, and therefore the whole bacterial chromosome is a replicon. The chromosomes of archaea and eukaryotes can have multiple origins of replication, and so their chromosomes may consist of several replicons. The concept of the replicon was formulated in 1963 by François Jacob, Sydney Brenner, and Jacques Cuzin as a part of their replicon model for replication initiation. According to the replicon model, two components control replication initiation: the replicator and the initiator. The replicator is the entire DNA sequence (including, but not limited to the origin of replication) required to direct the initiation of DNA replication. The initiator is the protein that recognizes the replicator and activates replication initiation. Sometimes in bacteriology, the term "replicon" is only used to refer to chromosomes containing ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Origin Of Replication

The origin of replication (also called the replication origin) is a particular sequence in a genome at which replication is initiated. Propagation of the genetic material between generations requires timely and accurate duplication of DNA by semiconservative replication prior to cell division to ensure each daughter cell receives the full complement of chromosomes. Material was copied from this source, which is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License This can either involve the DNA replication, replication of DNA in living organisms such as prokaryotes and eukaryotes, or that of DNA virus, DNA or RNA virus, RNA in viruses, such as double-stranded RNA viruses. Synthesis of daughter strands starts at discrete sites, termed replication origins, and proceeds in a bidirectional manner until all genomic DNA is replicated. Despite the fundamental nature of these events, organisms have evolved surprisingly divergent strategies that control replication onset. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and archaea; however plasmids are sometimes present in and eukaryotic organisms as well. Plasmids often carry useful genes, such as those involved in antibiotic resistance, virulence, secondary metabolism and bioremediation. While chromosomes are large and contain all the essential genetic information for living under normal conditions, plasmids are usually very small and contain additional genes for special circumstances. Artificial plasmids are widely used as vectors in molecular cloning, serving to drive the replication of recombinant DNA sequences within host organisms. In the laboratory, plasmids may be introduced into a cell via transformation. Synthetic plasmids are available for procurement over the internet by various vendors ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Viroid

Viroids are small single-stranded, circular RNAs that are infectious pathogens. Unlike viruses, they have no protein coating. All known viroids are inhabitants of angiosperms (flowering plants), and most cause diseases, whose respective economic importance to humans varies widely. A recent metatranscriptomics study suggests that the host diversity of viroids and viroid-like elements is broader than previously thought and that it would not be limited to plants, encompassing even the prokaryotes. The first discoveries of viroids in the 1970s triggered the historically third major extension of the biosphere—to include smaller lifelike entities—after the discoveries in 1675 by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (of the "subvisible" microorganisms) and in 1892–1898 by Dmitri Iosifovich Ivanovsky and Martinus Beijerinck (of the "submicroscopic" viruses). The unique properties of viroids have been recognized by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, in creating a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Retrotransposon

Retrotransposons (also called Class I transposable elements) are mobile elements which move in the host genome by converting their transcribed RNA into DNA through reverse transcription. Thus, they differ from Class II transposable elements, or DNA transposons, in utilizing an RNA intermediate for the transposition and leaving the transposition donor site unchanged. Through reverse transcription, retrotransposons amplify themselves quickly to become abundant in eukaryotic genomes such as maize (49–78%) and humans (42%). They are only present in eukaryotes but share features with retroviruses such as HIV, for example, discontinuous reverse transcriptase-mediated extrachromosomal recombination. There are two main types of retrotransposons, long terminal repeats (LTRs) and non-long terminal repeats (non-LTRs). Retrotransposons are classified based on sequence and method of transposition. Most retrotransposons in the maize genome are LTR, whereas in humans they are mostly non-L ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Transposon

A transposable element (TE), also transposon, or jumping gene, is a type of mobile genetic element, a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome. The discovery of mobile genetic elements earned Barbara McClintock a Nobel Prize in 1983. There are at least two classes of TEs: Class I TEs or retrotransposons generally function via reverse transcription, while Class II TEs or DNA transposons encode the protein transposase, which they require for insertion and excision, and some of these TEs also encode other proteins. Discovery by Barbara McClintock Barbara McClintock discovered the first TEs in maize (''Zea mays'') at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. McClintock was experimenting with maize plants that had broken chromosomes. In the winter of 1944–1945, McClintock planted corn kernels that were self-pollinated, meaning that the silk (style) of the flower received pollen from its own anther. These kernels came from a long lin ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Virus

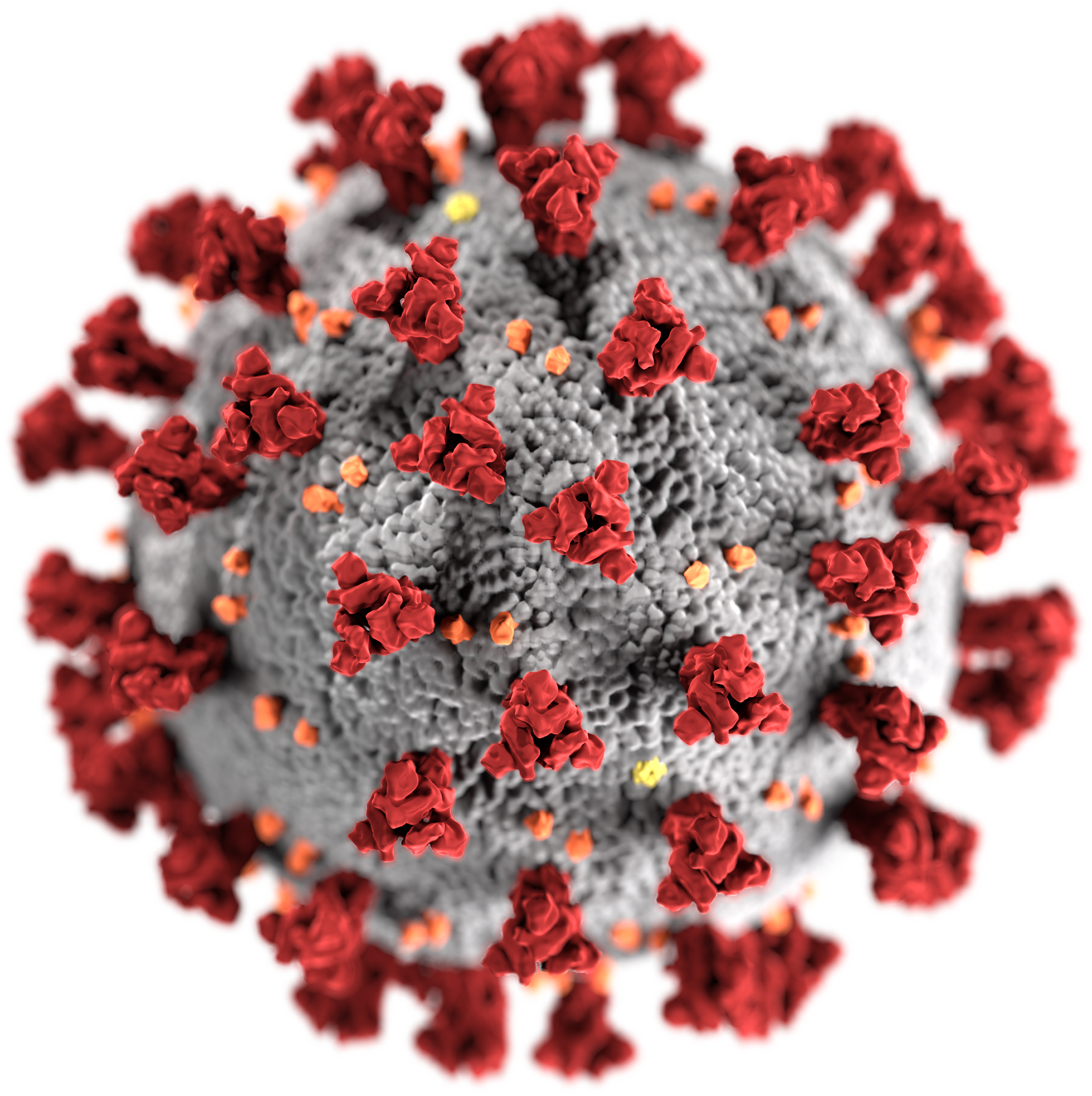

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are found in almost every ecosystem on Earth and are the most numerous type of biological entity. Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1892 article describing a non-bacterial pathogen infecting tobacco plants and the discovery of the tobacco mosaic virus by Martinus Beijerinck in 1898, more than 16,000 of the millions of List of virus species, virus species have been described in detail. The study of viruses is known as virology, a subspeciality of microbiology. When infected, a host cell is often forced to rapidly produce thousands of copies of the original virus. When not inside an infected cell or in the process of infecting a cell, viruses exist in the form of independent viral particles, or ''virions'', consisting of (i) genetic material, i.e., long ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Non-cellular Life

Non-cellular life, also known as acellular life, is life that exists without a cellular structure for at least part of its life cycle. Historically, most definitions of life postulated that an organism must be composed of one or more cells, but, for some, this is no longer considered necessary, and modern criteria allow for forms of life based on other structural arrangements. Nucleic acid-containing infectious agents Viruses Researchers initially described viruses as "poisons" or "toxins", then as "infectious proteins"; but they possess genetic material, a defined structure, and the ability to spontaneously assemble from their constituent parts. This has spurred extensive debate as to whether they should be regarded as fundamentally biotic or abiotic—as very small biological organisms or as very large biochemical molecules. Without their hosts, they are not able to perform any of the functions of life—such as metabolism, growth, or reproduction. Since the 195 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mitochondrion

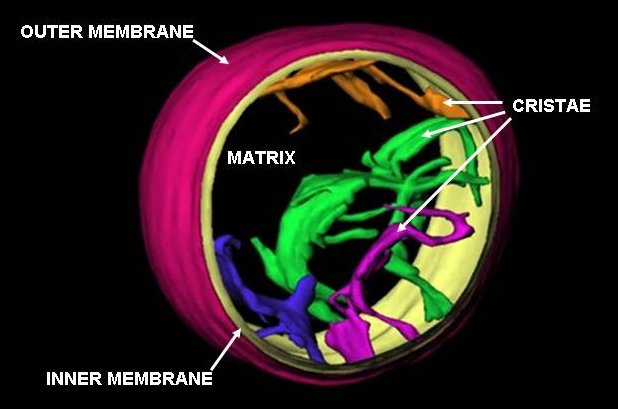

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cell (biology), cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used throughout the cell as a source of chemical energy. They were discovered by Albert von Kölliker in 1857 in the voluntary muscles of insects. The term ''mitochondrion'', meaning a thread-like granule, was coined by Carl Benda in 1898. The mitochondrion is popularly nicknamed the "powerhouse of the cell", a phrase popularized by Philip Siekevitz in a 1957 ''Scientific American'' article of the same name. Some cells in some multicellular organisms lack mitochondria (for example, mature mammalian red blood cells). The multicellular animal ''Henneguya zschokkei, Henneguya salminicola'' is known to have retained mitochondrion-related organelles despite a complete loss of their mitochondrial genome. A large number ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Model Organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Model organisms are widely used to research human disease when human experimentation would be unfeasible or unethical. This strategy is made possible by the common descent of all living organisms, and the conservation of metabolic and developmental pathways and genetic material over the course of evolution. Research using animal models has been central to most of the achievements of modern medicine. It has contributed most of the basic knowledge in fields such as human physiology and biochemistry, and has played significant roles in fields such as neuroscience and infectious disease. The results have included the near- eradication of polio and the development of organ transplantation, and have benefited both humans and animals. From 19 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers attach to the centromere via the kinetochore. The physical role of the centromere is to act as the site of assembly of the kinetochores – a highly complex multiprotein structure that is responsible for the actual events of chromosome segregation – i.e. binding microtubules and signaling to the cell cycle machinery when all chromosomes have adopted correct attachments to the spindle, so that it is safe for cell division to proceed to completion and for cells to enter anaphase. There are, broadly speaking, two types of centromeres. "Point centromeres" bind to specific proteins that recognize particular DNA sequences with high efficiency. Any piece of DNA with the point centromere DNA sequence on it will typically form a centr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

S Phase

S phase (Synthesis phase) is the phase of the cell cycle in which DNA is replicated, occurring between G1 phase and G2 phase. Since accurate duplication of the genome is critical to successful cell division, the processes that occur during S-phase are tightly regulated and widely conserved. Regulation Entry into S-phase is controlled by the G1 restriction point (R), which commits cells to the remainder of the cell-cycle if there is adequate nutrients and growth signaling. This transition is essentially irreversible; after passing the restriction point, the cell will progress through S-phase even if environmental conditions become unfavorable. Accordingly, entry into S-phase is controlled by molecular pathways that facilitate a rapid, unidirectional shift in cell state. In yeast, for instance, cell growth induces accumulation of Cln3 cyclin, which complexes with the cyclin dependent kinase CDK2. The Cln3-CDK2 complex promotes transcription of S-phase genes by inactivating ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Kilobase

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA and RNA. Dictated by specific hydrogen bonding patterns, "Watson–Crick" (or "Watson–Crick–Franklin") base pairs (guanine–cytosine and adenine– thymine) allow the DNA helix to maintain a regular helical structure that is subtly dependent on its nucleotide sequence. The complementary nature of this based-paired structure provides a redundant copy of the genetic information encoded within each strand of DNA. The regular structure and data redundancy provided by the DNA double helix make DNA well suited to the storage of genetic information, while base-pairing between DNA and incoming nucleotides provides the mechanism through which DNA polymerase replicates DNA and RNA polymerase transcribes DNA into RNA. Many DNA-binding protein ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |