|

Magnetic Tail

In astronomy and planetary science, a magnetosphere is a region of space surrounding an astronomical object in which charged particles are affected by that object's magnetic field. It is created by a celestial body with an active interior dynamo. In the space environment close to a planetary body, the magnetic field resembles a magnetic dipole. Farther out, field lines can be significantly distorted by the flow of electrically conducting plasma, as emitted from the Sun (i.e., the solar wind) or a nearby star. Planets having active magnetospheres, like the Earth, are capable of mitigating or blocking the effects of solar radiation or cosmic radiation, that also protects all living organisms from potentially detrimental and dangerous consequences. This is studied under the specialized scientific subjects of plasma physics, space physics and aeronomy. History Study of Earth's magnetosphere began in 1600, when William Gilbert discovered that the magnetic field on the surfa ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cosmic Radiation

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own galaxy, and from distant galaxies. Upon impact with Earth's atmosphere, cosmic rays produce showers of secondary particles, some of which reach the surface, although the bulk is deflected off into space by the magnetosphere or the heliosphere. Cosmic rays were discovered by Victor Hess in 1912 in balloon experiments, for which he was awarded the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physics. Direct measurement of cosmic rays, especially at lower energies, has been possible since the launch of the first satellites in the late 1950s. Particle detectors similar to those used in nuclear and high-energy physics are used on satellites and space probes for research into cosmic rays. Data from the Fermi Space Telescope (2013) have been interpreted as evidence ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Explorer 1

Explorer 1 was the first satellite launched by the United States in 1958 and was part of the U.S. participation in the International Geophysical Year (IGY). The mission followed the first two satellites the previous year; the Soviet Union's Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2, beginning the Cold War Space Race between the two nations. Explorer 1 was launched on 1 February 1958 at 03:47:56 GMT (or 31 January 1958 at 22:47:56 Eastern Time) atop the first Juno booster from LC-26A at the Cape Canaveral Missile Test Center of the Atlantic Missile Range (AMR), in Florida. It was the first spacecraft to detect the Van Allen radiation belt, returning data until its batteries were exhausted after nearly four months. It remained in orbit until 1970. Explorer 1 was given Satellite Catalog Number 00004 and the Harvard designation 1958 Alpha 1, the forerunner to the modern International Designator. Background The U.S. Earth satellite program began in 1954 as a joint U.S. Army and U.S. Navy pr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cosmic Rays

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own galaxy, and from distant galaxies. Upon impact with Earth's atmosphere, cosmic rays produce showers of secondary particles, some of which reach the surface, although the bulk is deflected off into space by the magnetosphere or the heliosphere. Cosmic rays were discovered by Victor Hess in 1912 in balloon experiments, for which he was awarded the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physics. Direct measurement of cosmic rays, especially at lower energies, has been possible since the launch of the first satellites in the late 1950s. Particle detectors similar to those used in nuclear and high-energy physics are used on satellites and space probes for research into cosmic rays. Data from the Fermi Space Telescope (2013) have been interpreted as evidence ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

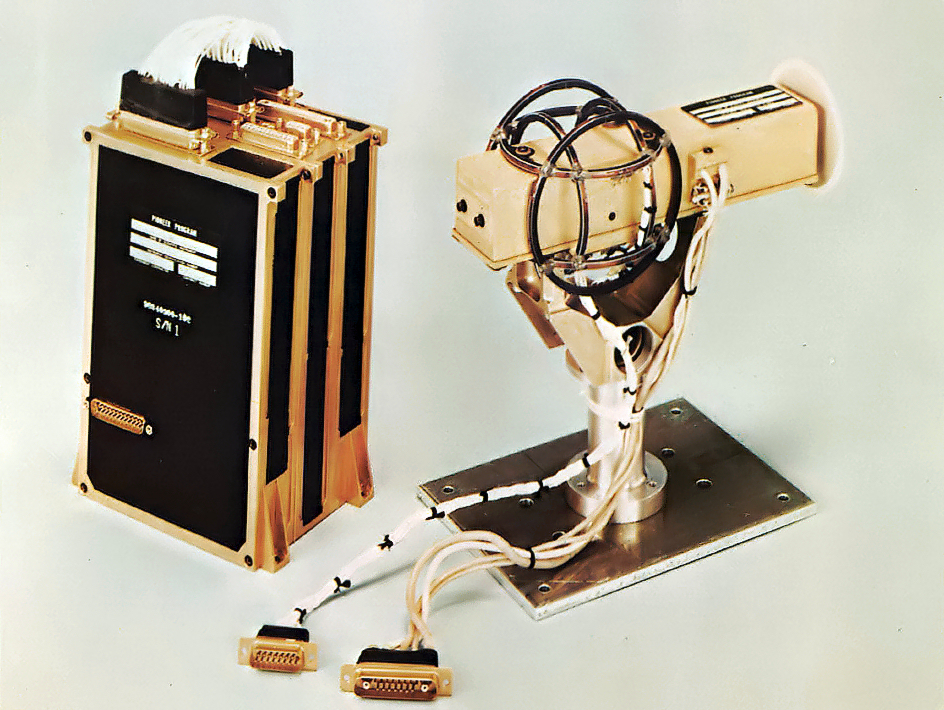

Magnetometer

A magnetometer is a device that measures magnetic field or magnetic dipole moment. Different types of magnetometers measure the direction, strength, or relative change of a magnetic field at a particular location. A compass is one such device, one that measures the direction of an ambient magnetic field, in this case, the Earth's magnetic field. Other magnetometers measure the magnetic dipole moment of a magnetic material such as a ferromagnet, for example by recording the effect of this magnetic dipole on the induced current in a coil. The first magnetometer capable of measuring the absolute magnetic intensity at a point in space was invented by Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1833 and notable developments in the 19th century included the Hall effect, which is still widely used. Magnetometers are widely used for measuring the Earth's magnetic field, in geophysical surveys, to detect magnetic anomalies of various types, and to determine the dipole moment of magnetic materials. In an air ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Outer Core

Earth's outer core is a fluid layer about thick, composed of mostly iron and nickel that lies above Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle. The outer core begins approximately beneath Earth's surface at the core-mantle boundary and ends beneath Earth's surface at the inner core boundary. Properties Unlike Earth's solid, inner core, its outer core is liquid. Evidence for a fluid outer core includes seismology which shows that seismic shear-waves are not transmitted through the outer core. Although having a composition similar to Earth's solid inner core, the outer core remains liquid as there is not enough pressure to keep it in a solid state. Seismic inversions of body waves and normal modes constrain the radius of the outer core to be 3483 km with an uncertainty of 5 km, while that of the inner core is 1220±10 km. Estimates for the temperature of the outer core are about in its outer region and near the inner core. Modeling has shown that the outer core, be ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in front of oxygen (32.1% and 30.1%, respectively), forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust. In its metallic state, iron is rare in the Earth's crust, limited mainly to deposition by meteorites. Iron ores, by contrast, are among the most abundant in the Earth's crust, although extracting usable metal from them requires kilns or furnaces capable of reaching or higher, about higher than that required to smelt copper. Humans started to master that process in Eurasia during the 2nd millennium BCE and the use of iron tools and weapons began to displace copper alloys, in some regions, only around 1200 BCE. That event is considered the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron A ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Earth's Magnetic Field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic field is generated by electric currents due to the motion of convection currents of a mixture of molten iron and nickel in Earth's outer core: these convection currents are caused by heat escaping from the core, a natural process called a geodynamo. The magnitude of Earth's magnetic field at its surface ranges from . As an approximation, it is represented by a field of a magnetic dipole currently tilted at an angle of about 11° with respect to Earth's rotational axis, as if there were an enormous bar magnet placed at that angle through the center of Earth. The North geomagnetic pole actually represents the South pole of Earth's magnetic field, and conversely the South geomagnetic pole corresponds to the north pole of Earth's magnetic ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Dynamo Theory

In physics, the dynamo theory proposes a mechanism by which a celestial body such as Earth or a star generates a magnetic field. The dynamo theory describes the process through which a rotating, convecting, and electrically conducting fluid can maintain a magnetic field over astronomical time scales. A dynamo is thought to be the source of the Earth's magnetic field and the magnetic fields of Mercury and the Jovian planets. History of theory When William Gilbert published ''de Magnete'' in 1600, he concluded that the Earth is magnetic and proposed the first hypothesis for the origin of this magnetism: permanent magnetism such as that found in lodestone. In 1919, Joseph Larmor proposed that a dynamo might be generating the field. However, even after he advanced his hypothesis, some prominent scientists advanced alternative explanations. Einstein believed that there might be an asymmetry between the charges of the electron and proton so that the Earth's magnetic field would ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Walter M

Walter may refer to: People * Walter (name), both a surname and a given name * Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–1968) * Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born 1987), who previously wrestled as "Walter" * Walter, standard author abbreviation for Thomas Walter (botanist) ( – 1789) Companies * American Chocolate, later called Walter, an American automobile manufactured from 1902 to 1906 * Walter Energy, a metallurgical coal producer for the global steel industry * Walter Aircraft Engines, Czech manufacturer of aero-engines Films and television * ''Walter'' (1982 film), a British television drama film * Walter Vetrivel, a 1993 Tamil crime drama film * ''Walter'' (2014 film), a British television crime drama * ''Walter'' (2015 film), an American comedy-drama film * ''Walter'' (2020 film), an Indian crime drama film * ''W*A*L*T*E*R'', a 1984 pilot for a spin-off of the TV series ''M*A*S*H'' * ''W ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Terrella

A terrella (Latin for "little earth") is a small magnetised model ball representing the Earth, that is thought to have been invented by the English physician William Gilbert while investigating magnetism, and further developed 300 years later by the Norwegian scientist and explorer Kristian Birkeland, while investigating the aurora. Terrellas have been used until the late 20th century to attempt to simulate the Earth's magnetosphere, but have now been replaced by computer simulations. William Gilbert's terrella William Gilbert, the royal physician to Queen Elizabeth I, devoted much of his time, energy and resources to the study of the Earth's magnetism. It had been known for centuries that a freely suspended compass needle pointed north. Earlier investigators (including Christopher Columbus) found that direction deviated somewhat from true north, and Robert Norman showed the force on the needle was not horizontal but slanted into the Earth. William Gilbert's explanation was ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

William Gilbert (astronomer)

William Gilbert (; 24 May 1544? – 30 November 1603), also known as Gilberd, was an English physician, physicist and natural philosopher. He passionately rejected both the prevailing Aristotelian philosophy and the Scholastic method of university teaching. He is remembered today largely for his book ''De Magnete'' (1600). A unit of magnetomotive force, also known as magnetic potential, was named the ''Gilbert'' in his honour. Life and work Gilbert was born in Colchester to Jerome Gilberd, a borough recorder. He was educated at St John's College, Cambridge. After gaining his MD from Cambridge in 1569, and a short spell as bursar of St John's College, he left to practice medicine in London and travelled on the continent. In 1573, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. In 1600 he was elected President of the college.Mottelay, P. Fleury (1893). "Biographical memoir". In He was Elizabeth I's own physician from 1601 until her death in 1603, and James ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |