|

Carceral Archipelago

The concept of a carceral archipelago was first used by the French historian and philosopher Michel Foucault in his 1975 publication, '' Surveiller et Punir'', to describe the modern penal system of the 1970s, embodied by the well-known penal institution at Mettray in France. The phrase combines the adjective "carceral", which means that which is related to jail or prison, with archipelago—a group of islands. Foucault referred to the "island" units of the "archipelago" as a metaphor for the mechanisms, technologies, knowledge systems and networks related to a carceral continuum. The 1973 English publication of the book by Solzhenitsyn called ''The Gulag Archipelago'' referred to the forced labor camps and prisons that composed the sprawling carceral network of the Soviet Gulag. Concepts developed in Foucault's ''Discipline and Punish'' have been widely used by researchers in the growing, multi-disciplinary field of "carceral state" studies, as part of the "carceral turn" in the 1 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

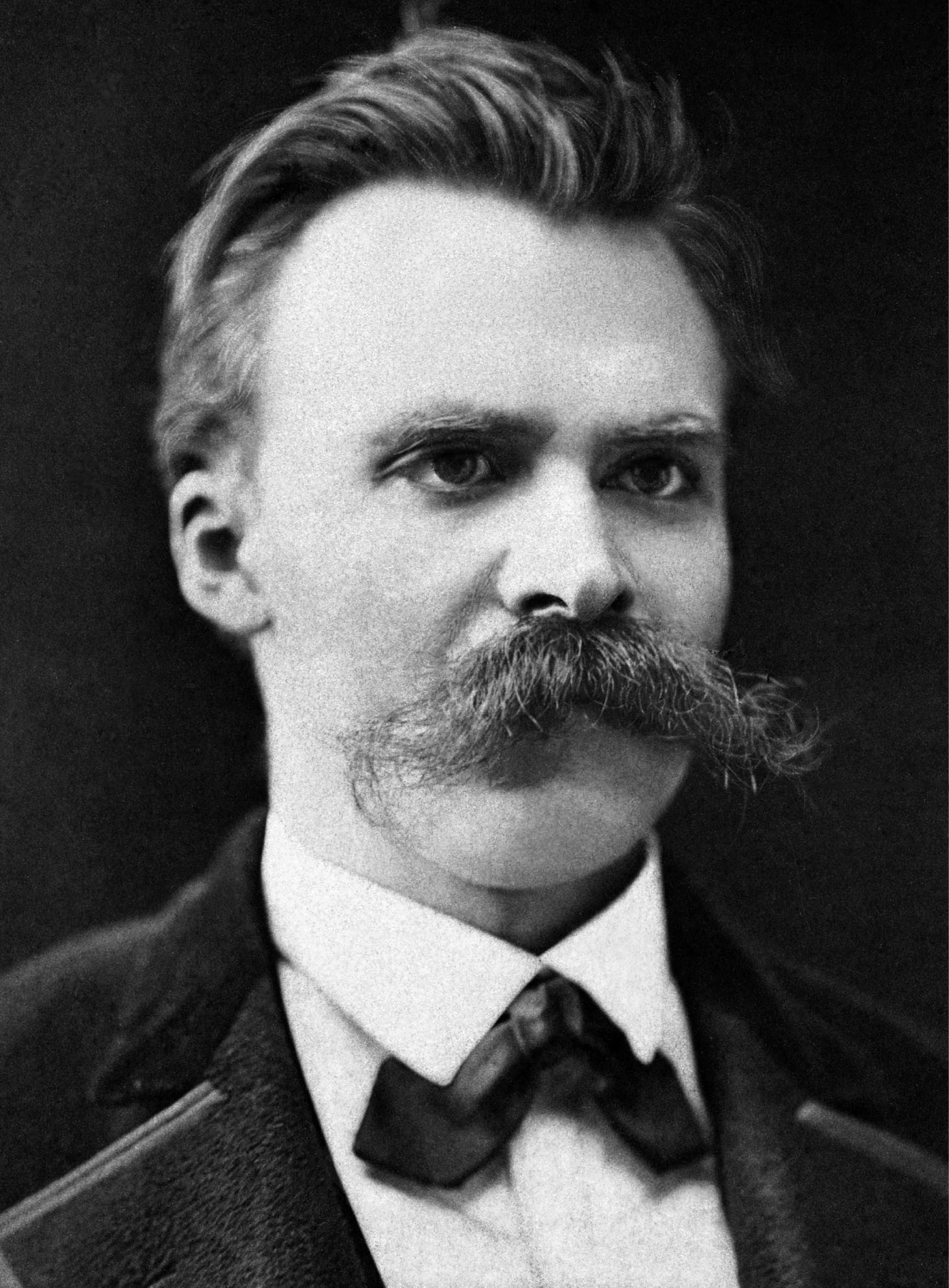

Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault (, ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, writer, political activist, and literary critic. Foucault's theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. Though often cited as a structuralist and postmodernist, Foucault rejected these labels. His thought has influenced academics, especially those working in communication studies, anthropology, psychology, sociology, criminology, cultural studies, literary theory, feminism, Marxism and critical theory. Born in Poitiers, France, into an upper-middle-class family, Foucault was educated at the Lycée Henri-IV, at the École Normale Supérieure, where he developed an interest in philosophy and came under the influence of his tutors Jean Hyppolite and Louis Althusser, and at the University of Paris (Sorbonne), where he earned degrees in philosophy and psychology. Aft ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Éditions Gallimard

Éditions Gallimard (), formerly Éditions de la Nouvelle Revue Française (1911–1919) and Librairie Gallimard (1919–1961), is one of the leading French book publishers. In 2003 it and its subsidiaries published 1,418 titles. Founded by Gaston Gallimard in 1911, the publisher is now majority-owned by his grandson Antoine Gallimard. Éditions Gallimard is a subsidiary of Groupe Madrigall, the third largest French publishing group. History The publisher was founded on 31 May 1911 in Paris by Gaston Gallimard, André Gide, and Jean Schlumberger as ''Les Éditions de la Nouvelle Revue Française'' (NRF). From its 31 May 1911 founding until June 1919, Nouvelle Revue Française published one hundred titles including ''La Jeune Parque'' by Paul Valéry. NRF published the second volume of '' In Search of Lost Time'', In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, which became the first Prix Goncourt-awarded book published by the company. Nouvelle Revue Française adopted the name "Li ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Private Investigator

A private investigator (often abbreviated to PI and informally called a private eye), a private detective, or inquiry agent is a person who can be hired by individuals or groups to undertake investigatory law services. Private investigators often work for attorneys in civil and criminal cases. History In 1833, Eugène François Vidocq, a French soldier, criminal, and privateer, founded the first known private detective agency, "Le Bureau des Renseignements Universels pour le commerce et l'Industrie" ("The Office of Universal Information For Commerce and Industry") and hired ex-convicts. Much of what private investigators did in the early days was to act as the police in matters for which their clients felt the police were not equipped or willing to do. Official law enforcement tried many times to shut it down. In 1842, police arrested him in suspicion of unlawful imprisonment and taking money on false pretences after he had solved an embezzlement case. Vidocq later suspecte ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

National Police (France)

The National Police (french: Police nationale), formerly known as the , is one of two national police forces of France, the other being the National Gendarmerie. The National Police is the country's main civil law enforcement agency, with primary jurisdiction in cities and large towns. By contrast, the National Gendarmerie has primary jurisdiction in smaller towns, as well as in rural and border areas. The National Police comes under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior and has about 145,200 employees (as of 2015). Young French citizens can fulfill their mandatory service (''Service national universel'') in the police force. The National Police operates mostly in cities and large towns. In that context, it conducts security operations such as patrols, traffic control and identity checks. Under the orders and supervision of investigating magistrates of the judiciary, it conducts criminal inquiries and serves search warrants. It also maintains specific services ('judic ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Criminal

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Cane and Conoghan (editors), ''The New Oxford Companion to Law'', Oxford University Press, 2008 (), p. 263Google Books). though statutory definitions have been provided for certain purposes. The most popular view is that crime is a category created by law; in other words, something is a crime if declared as such by the relevant and applicable law. One proposed definition is that a crime or offence (or criminal offence) is an act harmful not only to some individual but also to a community, society, or the state ("a public wrong"). Such acts are forbidden and punishable by law. The notion that acts such as murder, rape, and theft are to be prohibited exists worldwide. What precisely is a criminal offence is defined by the criminal law of each r ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

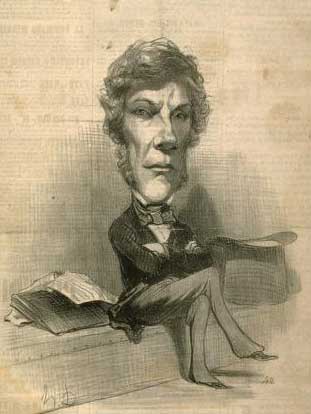

Eugène François Vidocq

Eugène-François Vidocq (; 24 July 1775 – 11 May 1857) was a French criminal turned criminalist, whose life story inspired several writers, including Victor Hugo, Edgar Allan Poe and Honoré de Balzac. The former criminal became the founder and first director of the crime-detection Sûreté nationale as well as the head of the first known private detective agency. Vidocq is considered to be the father of modern criminologySiegel, Jay A.: ''Forensic Science: The Basics''. CRC Press, 2006, , S. 12.Conser, James Andrew and Russell, Gregory D.: ''Law Enforcement in the United States.'' Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2005, , S. 39. and of the French police department. He is also regarded as the first private detective. Biography Eugène François Vidocq was born in Arras, northern France, during the night of 23/24 July 1775, in the Rue du Miroir-de-Venise, nowadays the Rue Eugène-François Vidocq. He was the third child of Henriette Françoise Vidocq (maiden name Dion, 1744–182 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

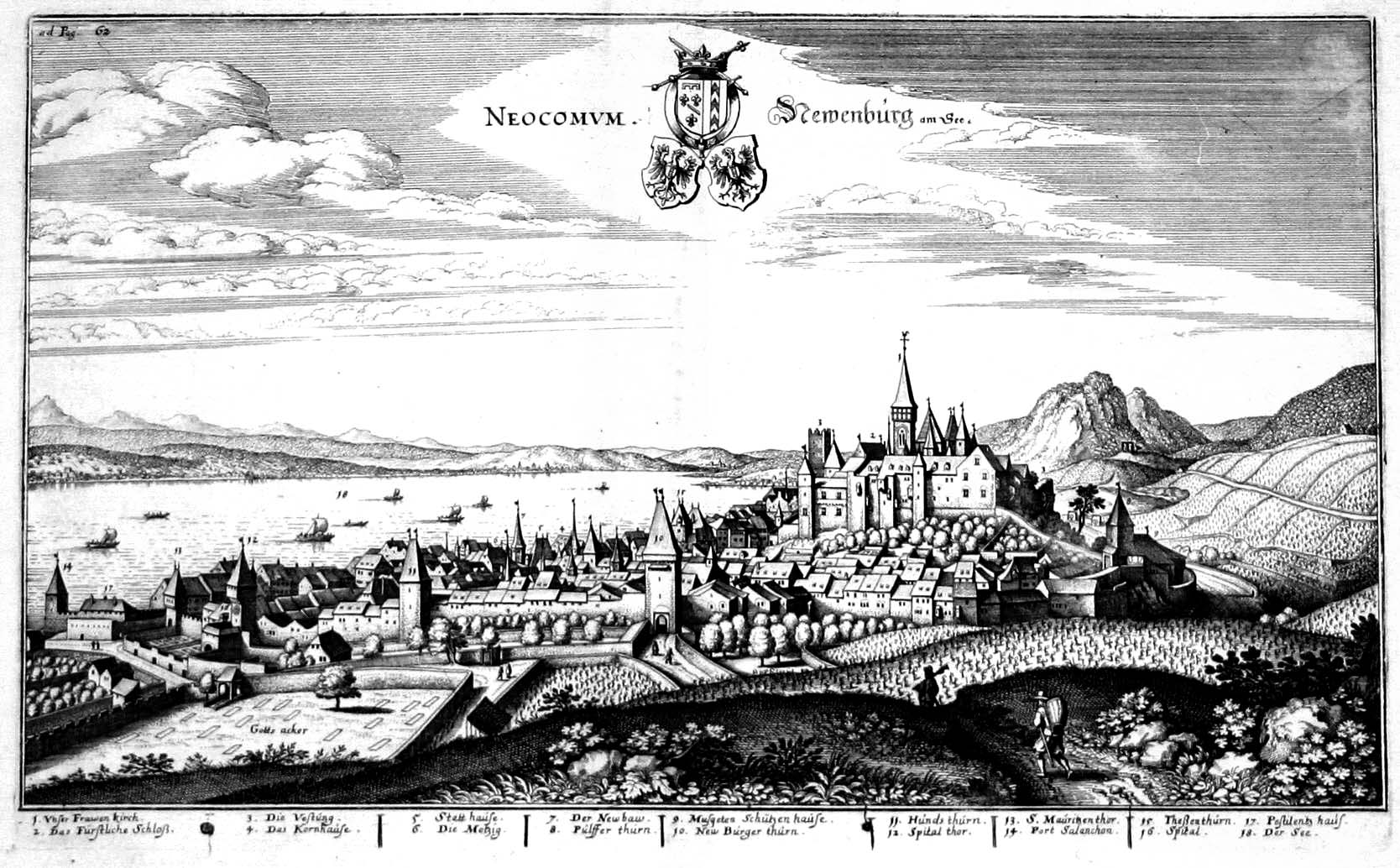

Neuchâtel

, neighboring_municipalities= Auvernier, Boudry, Chabrey (VD), Colombier, Cressier, Cudrefin (VD), Delley-Portalban (FR), Enges, Fenin-Vilars-Saules, Hauterive, Saint-Blaise, Savagnier , twintowns = Aarau (Switzerland), Besançon (France), Sansepolcro (Italy) Neuchâtel (, , ; german: Neuenburg) is the capital of the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel, situated on the shoreline of Lake Neuchâtel. Since the fusion in 2021 of the municipalities of Neuchâtel, Corcelles-Cormondrèche, Peseux, and Valangin, the city has approximately 45,000 inhabitants (80,000 in the metropolitan area). The city is sometimes referred to historically by the German name ; both the French and German names mean "New Castle". It was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy, then part of the Holy Roman Empire and later under Prussian control from 1707 until 1848, with an interruption during the Napoleonic Wars from 1802 to 1814. In 1848, Neuchâtel became a republic and a canton of Switzerland. Neuch� ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Léon Faucher

Léonard Joseph (Léon) Faucher (; 8 September 1803 – 14 December 1854) was a French politician and economist. Biography Faucher was born at Limoges, Haute-Vienne. When he was nine years old the family moved to Toulouse, where the boy was sent to school. His parents were separated in 1816, and Léon Faucher, who resisted his father's attempts to put him to a trade, helped to support himself and his mother during the rest of his school career by designing embroidery and needlework. As a private tutor in Paris he continued his studies in the direction of archaeology and history, but with the revolution of 1830 he was drawn into active political journalism on the Liberal side. He was on the staff of the ''Temps'' from 1830 to 1833, when he became editor of the ''Constitutionnel'' for a short time. A Sunday journal of his own, ''Le Bien public'', proved a disastrous financial failure; and his political independence having caused his retirement from the ''Constitutionnel'', he joi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Charles Lucas

Sir Charles Lucas, 1613 to 28 August 1648, was a professional soldier from Essex, who served as a Cavalier, Royalist cavalry leader during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Taken prisoner at the end of the First English Civil War in March 1646, he was released after swearing not to fight against Parliament of England, Parliament again, an oath he broke when the Second English Civil War began in 1648. As a result, he was executed following his capture at the Siege of Colchester in August 1648, and became a Royalist martyr after the 1660 Stuart Restoration. Royalist statesman and historian Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon, described Lucas as "rough, proud, uncultivated and morose", but "a gallant man to look upon and follow". A brave and capable cavalry commander with a reputation for bad temper and ruthlessness, he is chiefly remembered for the manner of his death. Personal details Charles Lucas was born in Colchester, Essex in 1613, youngest son of Sir Thomas Lucas (1573� ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Joseph Michel Antoine Servan

Joseph Michel Antoine Servan (November 3, 1737 – 1807) was a French publicist and lawyer. He was born at Romans (Dauphiné). After studying law he was appointed ''avocat-general'' at the '' parlement'' of Grenoble at the age of twenty-seven. In his ''Discours sur l'administration de la Justice Criminelle'' (1767) he made an eloquent protest against legal abuses and the severity of the criminal code. In 1767 he gained great repute for his defense of a Protestant woman who, as a result of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, had been abandoned by her Catholic husband. In 1772, however, on the parlement refusing to accede to his request that a present made by a ''grand seigneur'' to a singer should be annulled on the ground of immorality, he resigned, and went into retirement. He excused himself on the score of ill health from sitting in the States General of 1789, to which he had been elected deputy, and refused to take his seat in the ''Corps Législatif'' under the Empire. A ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Drawing And Quartering

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III (1216–1272). The convicted traitor was fastened to a hurdle, or wooden panel, and drawn by horse to the place of execution, where he was then hanged (almost to the point of death), emasculated, disembowelled, beheaded, and quartered (chopped into four pieces). His remains would then often be displayed in prominent places across the country, such as London Bridge, to serve as a warning of the fate of traitors. For reasons of public decency, women convicted of high treason were instead burned at the stake. The same punishment applied to traitors against the King in Ireland from the 15th century onward; William Overy was hanged, drawn and quartered by Lord Lieutenant Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York in 1469, and from the reign of K ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis'' and ''cida'' (''cidium''), meaning "of monarch" and "killer" respectively. In the British tradition, it refers to the judicial execution of a king after a trial, reflecting the historical precedent of the trial and execution of Charles I of England. The concept of regicide has also been explored in media and the arts through pieces like ''Macbeth'' (Macbeth's killing of King Duncan) and ''The Lion King''. History In Western Christianity, regicide was far more common prior to 1200/1300. Sverre Bagge counts 20 cases of regicide between 1200 and 1800, which means that 6% of monarchs were killed by their subjects. He counts 94 cases of regicide between 600 and 1200, which means that 21.8% of monarchs were killed by their subjects. He argues ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |