|

Curdlan

Curdlan is a water-insoluble linear beta-1,3-glucan, a high-molecular-weight polymer of glucose. Curdlan consists of β-(1,3)-linked glucose residues and forms elastic gels upon heating in aqueous suspension. It was reported to be produced by '' Alcaligenes faecalis'' var. ''myxogenes''. Subsequently, the taxonomy of this non-pathogenic curdlan-producing bacterium has been reclassified as ''Agrobacterium'' species. Extracellular and capsular polysaccharides are produced by a variety of pathogenic and soil-dwelling bacteria. Curdlan is a neutral β-(1,3)-glucan, perhaps with a few intra- or interchain 1,6-linkages, produced as an exopolysaccharide by soil bacteria of the family Rhizobiaceae. Four genes required for curdlan production have been identified in ''Agrobacterium'' sp. ATCC31749, which produces curdlan in extraordinary amounts, and ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens''. A putative operon In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under t ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Glucan

A glucan is a polysaccharide derived from D-glucose, linked by glycosidic bonds. Glucans are noted in two forms: alpha glucans and beta glucans. Many beta-glucans are medically important. They represent a drug target for antifungal medications of the echinocandin class. In the field of bacteriology, the term polyglucan is used to describe high molecular mass glucans. They are structural polysaccharide consisting of a long linear chain of several hundred to many thousands D-glucose monomers. The point of attachment is O-glycosidic bonds, where a glycosidic oxygen links the glycoside to the reducing end sugar. Polyglucans naturally occur in the cell walls of bacteria. Bacteria produce this polysaccharide in a cluster near the bacteria's cells. Polyglucan's are a source of beta-glucans. Structurally, beta 1.3-glucans are complex glucose homopolymers binding together in a beta-1,3 configuration. Types The following are glucans (The α- and β- and numbers clarify the type of O-gly ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 electrons. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon makes up about 0.025 percent of Earth's crust. Three Isotopes of carbon, isotopes occur naturally, carbon-12, C and carbon-13, C being stable, while carbon-14, C is a radionuclide, decaying with a half-life of 5,700 years. Carbon is one of the timeline of chemical element discoveries#Pre-modern and early modern discoveries, few elements known since antiquity. Carbon is the 15th abundance of elements in Earth's crust, most abundant element in the Earth's crust, and the abundance of the chemical elements, fourth most abundant element in the universe by mass after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen. Carbon's abundance, its unique diversity of organic compounds, and its unusual abi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

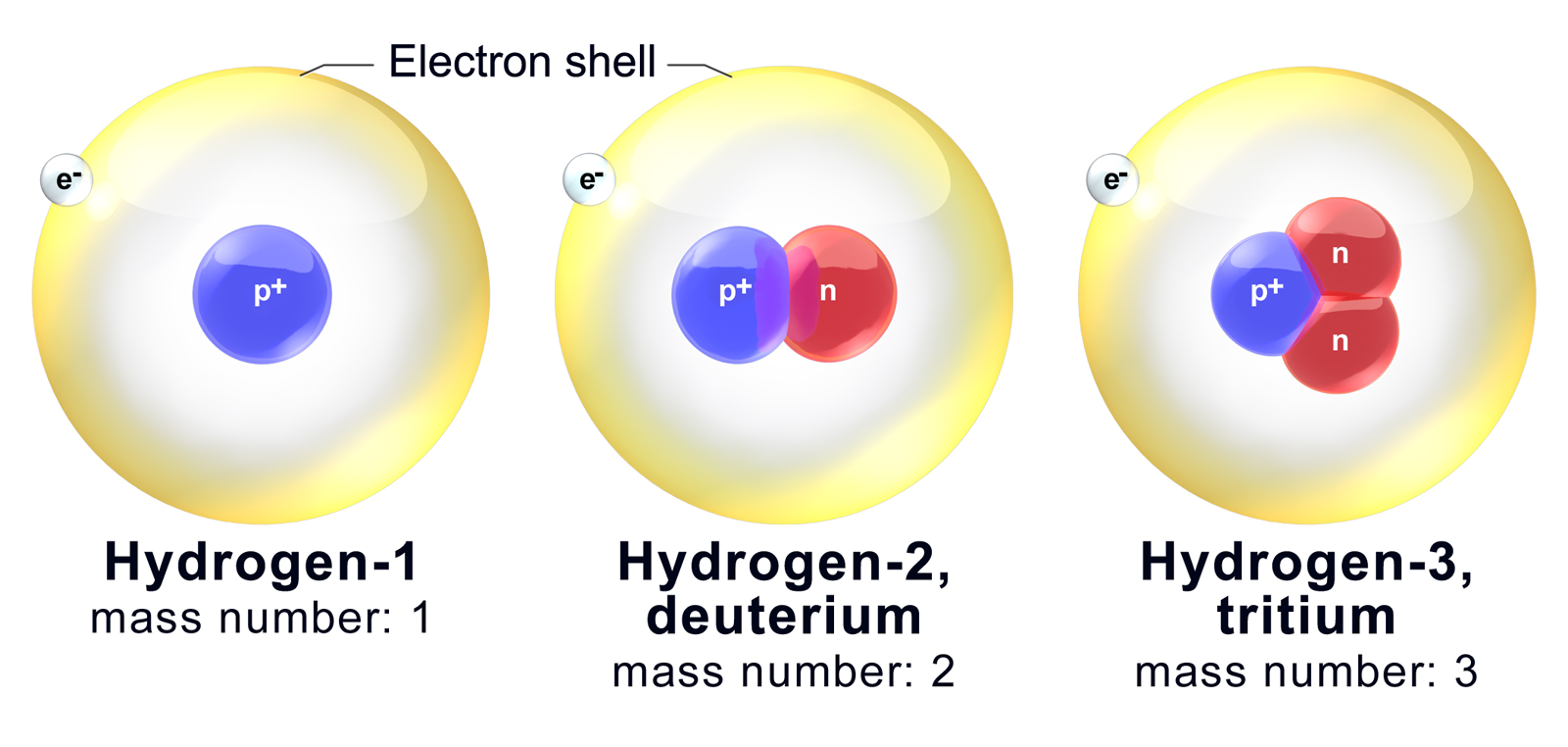

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter. Under standard conditions, hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules with the chemical formula, formula , called dihydrogen, or sometimes hydrogen gas, molecular hydrogen, or simply hydrogen. Dihydrogen is colorless, odorless, non-toxic, and highly combustible. Stars, including the Sun, mainly consist of hydrogen in a plasma state, while on Earth, hydrogen is found as the gas (dihydrogen) and in molecular forms, such as in water and organic compounds. The most common isotope of hydrogen (H) consists of one proton, one electron, and no neutrons. Hydrogen gas was first produced artificially in the 17th century by the reaction of acids with metals. Henry Cavendish, in 1766–1781, identified hydrogen gas as a distinct substance and discovere ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal, and a potent oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as well as with other chemical compound, compounds. Oxygen is abundance of elements in Earth's crust, the most abundant element in Earth's crust, making up almost half of the Earth's crust in the form of various oxides such as water, carbon dioxide, iron oxides and silicates.Atkins, P.; Jones, L.; Laverman, L. (2016).''Chemical Principles'', 7th edition. Freeman. It is abundance of chemical elements, the third-most abundant element in the universe after hydrogen and helium. At standard temperature and pressure, two oxygen atoms will chemical bond, bind covalent bond, covalently to form dioxygen, a colorless and odorless diatomic gas with the chemical formula ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using energy from sunlight. It is used by plants to make cellulose, the most abundant carbohydrate in the world, for use in cell walls, and by all living Organism, organisms to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used by the cell as energy. In energy metabolism, glucose is the most important source of energy in all organisms. Glucose for metabolism is stored as a polymer, in plants mainly as amylose and amylopectin, and in animals as glycogen. Glucose circulates in the blood of animals as blood sugar. The naturally occurring form is -glucose, while its Stereoisomerism, stereoisomer L-glucose, -glucose is produced synthetically in comparatively small amounts and is less biologicall ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Gels

A gel is a semi-solid that can have properties ranging from soft and weak to hard and tough. Gels are defined as a substantially dilute cross-linked system, which exhibits no flow when in the steady state, although the liquid phase may still diffuse through this system. Gels are mostly liquid by mass, yet they behave like solids because of a three-dimensional cross-linked network within the liquid. It is the cross-linking within the fluid that gives a gel its structure (hardness) and contributes to the adhesive stick ( tack). In this way, gels are a dispersion of molecules of a liquid within a solid medium. The word ''gel'' was coined by 19th-century Scottish chemist Thomas Graham by clipping from ''gelatine''. The process of forming a gel is called gelation. Composition Gels consist of a solid three-dimensional network that spans the volume of a liquid medium and ensnares it through surface tension effects. This internal network structure may result from physical b ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Suspension (chemistry)

In chemistry, a suspension is a heterogeneous mixture of a fluid that contains solid particles sufficiently large for sedimentation. The particles may be visible to the naked eye, usually must be larger than one micrometer, and will eventually settle, although the mixture is only classified as a suspension when and while the particles have not settled out. Properties A suspension is a heterogeneous mixture in which the solid particles do not dissolve, but get suspended throughout the bulk of the solvent, left floating around freely in the medium. The internal phase (solid) is dispersed throughout the external phase (fluid) through mechanical agitation, with the use of certain excipients or suspending agents. An example of a suspension would be sand in water. The suspended particles are visible under a microscope and will settle over time if left undisturbed. This distinguishes a suspension from a colloid, in which the colloid particles are smaller and do not settle. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Alcaligenes Faecalis

''Alcaligenes faecalis'' is a species of Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria commonly found in the environment. It was originally named for its first discovery in feces, but was later found to be common in soil, water, and environments in association with humans. While opportunistic infections do occur, the bacterium is generally considered nonpathogenic. When an opportunistic infection does occur, it is usually observed in the form of a urinary tract infection. ''A. faecalis'' has been used for the production of nonstandard amino acids. Description ''A. faecalis'' is a Gram-negative bacterium which appears rod-shaped and motile under a microscope. It is positive by the oxidase test and catalase test, but negative by the nitrate reductase test. It is alpha-hemolytic and requires oxygen. ''A. faecalis'' can be grown at 37 °C, and forms colonies that lack pigmentation. Metabolism The bacterium degrades urea, creating ammonia which increases the pH of the environment. Alt ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Agrobacterium

''Agrobacterium'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria established by Harold J. Conn, H. J. Conn that uses horizontal gene transfer to cause tumors in plants. ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' is the most commonly studied species in this genus. ''Agrobacterium'' is well known for its ability to transfer DNA between itself and plants, and for this reason it has become an important tool for genetic engineering. Nomenclatural history Leading up to the 1990s, the genus ''Agrobacterium'' was used as a wastebasket taxon. With the advent of 16S ribosomal RNA, 16S sequencing, many ''Agrobacterium'' species (especially the marine species) were reassigned to genera such as ''Ahrensia'', ''Pseudorhodobacter'', ''Ruegeria'', and ''Stappia''. The remaining ''Agrobacterium'' species were assigned to three biovars: biovar 1 (''Agrobacterium tumefaciens''), biovar 2 (''Agrobacterium rhizogenes''), and biovar 3 (''Agrobacterium vitis''). In the early 2000s, ''Agrobacterium'' was synonymized with the g ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Agrobacterium Tumefaciens

''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' (also known as ''Rhizobium radiobacter'') is the causal agent of crown gall disease (the formation of tumours) in over 140 species of eudicots. It is a rod-shaped, Gram-negative soil bacterium. Symptoms are caused by the insertion of a small segment of DNA (known as T-DNA, for 'transfer DNA', not to be confused with tRNA that transfers amino acids during protein synthesis), from a plasmid into the plant cell, which is incorporated at a semi-random location into the plant genome. Plant genomes can be engineered by use of '' Agrobacterium'' for the delivery of sequences hosted in T-DNA binary vectors. ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' is an Alphaproteobacterium of the family Rhizobiaceae, which includes the nitrogen-fixing legume symbionts. Unlike the nitrogen-fixing symbionts, tumor-producing ''Agrobacterium'' species are pathogenic and do not benefit the plant. The wide variety of plants affected by ''Agrobacterium'' makes it of great concern to ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splicing to create monocistronic mRNAs that are translated separately, i.e. several strands of mRNA that each encode a single gene product. The result of this is that the genes contained in the operon are either expressed together or not at all. Several genes must be ''co-transcribed'' to define an operon. Originally, operons were thought to exist solely in prokaryotes (which includes organelles like plastids that are derived from bacteria), but their discovery in eukaryotes was shown in the early 1990s, and are considered to be rare. In general, expression of prokaryotic operons leads to the generation of polycistronic mRNAs, while eukaryotic operons lead to monocistronic mRNAs. Operons are also found in viruses such as bacteriophages. For ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Callose

Callose is a plant polysaccharide. Its production is due to the glucan synthase-like gene (GLS) in various places within a plant. It is produced to act as a temporary cell wall in response to stimuli such as stress or damage. Callose is composed of glucose residues linked together through β-1,3-linkages, and is termed a β-glucan. It is thought to be manufactured at the cell wall by callose synthases and is degraded by β-1,3- glucanases. Callose is very important for the permeability of plasmodesmata (Pd) in plants; the plant's permeability is regulated by plasmodesmata callose (PDC). PDC is made by callose synthases and broken down by β-1,3-glucanases (BGs). The amount of callose that is built up at the plasmodesmatal neck, which is brought about by the interference of callose synthases (CalSs) and β-1,3-glucanases, determines the conductivity of the plasmodesmata. Formation and function Callose is laid down at plasmodesmata, at the cell plate during cytokinesis, and during ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |