|

Stang's Law

Stang's law is a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) phonological rule named after the Norwegian linguist Christian Stang. Overview The law governs the word-final sequences of a vowel, followed by a semivowel ( or ) or a laryngeal ( or ), followed by a nasal. According to the law these sequences are simplified such that laryngeals and semivowels are dropped, with compensatory lengthening of a preceding vowel. This rule is usually cited in more restricted form as: and ( denoting a vowel and a long vowel). Often the rules and also are added: * PIE 'sky' (accusative singular) > > Sanskrit ''dyā́m'', acc. sg. of ''dyaús'', Latin ''diem'' (which served as the basis for Latin ''diēs'' 'day'), Greek Ζῆν (''Zên'') (reformed after Homeric Greek to Ζῆνα ''Zêna'', subsequently Δία ''Día''), acc. of Ζεύς (''Zeús'') * PIE 'cow' (acc. sg.) > > Sanskrit ''gā́m'', acc. sg. of ''gaús'', Greek (Homeric and dialectal) βών (''bṓn''), acc. sg. of βοῦς (''boûs' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Proto-Indo-European Language

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists. Far more work has gone into reconstructing PIE than any other proto-language, and it is the best understood of all proto-languages of its age. The majority of linguistic work during the 19th century was devoted to the reconstruction of PIE or its daughter languages, and many of the modern techniques of linguistic reconstruction (such as the comparative method) were developed as a result. PIE is hypothesized to have been spoken as a single language from 4500 BC to 2500 BC during the Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age, though estimates vary by more than a thousand years. According to the prevailing Kurgan hypothesis, the original homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans may have been in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Proto-Indo-European Phonology

The phonology of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) has been reconstructed by linguists, based on the similarities and differences among current and extinct Indo-European languages. Because PIE was not written, linguists must rely on the evidence of its earliest attested descendants, such as Hittite, Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, and Latin, to reconstruct its phonology. The reconstruction of abstract units of PIE phonological systems (i.e. segments, or phonemes in traditional phonology) is mostly uncontroversial, although areas of dispute remain. Their phonetic interpretation is harder to establish; this pertains especially to the vowels, the so-called laryngeals, the palatal and plain velars and the voiced and voiced aspirated stops. Phonemic inventory Proto-Indo-European is reconstructed to have used the following phonemes. See the article on Indo-European sound laws for a summary of how these phonemes reflected in the various Indo-European languages. Consonants The ta ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

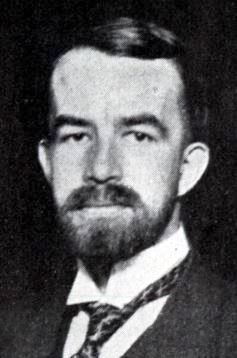

Christian Stang

Christian Schweigaard Stang (15 March 1900 – 2 July 1977) was a Norwegian linguist, Slavicist and Balticist, professor in Balto-Slavic languages at the University of Oslo from 1938 until shortly before his death. He specialized in the study of Lithuanian and was highly regarded in Lithuania. Early life He was born in Kristiania as a son of politician and academic Fredrik Stang (1867–1941) and his wife Caroline Schweigaard (1871–1900). He was a grandson of Emil Stang and Christian Homann Schweigaard, and a nephew of Emil Stang, Jr. He grew up in Kristiania and took his examen artium 1918 at Frogner School. Career He received his magister degree in comparative Indo-European linguistics in 1927, and his Ph.D. in 1929. Subsequently, he was the University Fellow in comparative Indo-European linguistics for the period 1928–33. From 1938 to 1970 he was professor of Slavonic languages at the University of Oslo. He served as the dean of the Faculty of Humanities from 1958 to 1960 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Laryngeal Theory

The laryngeal theory is a theory in the historical linguistics of the Indo-European languages positing that: * The Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) had a series of phonemes beyond those reconstructable by the comparative method. That is, the theory maintains that there were sounds in Proto-Indo-European that no longer exist in any of the daughter languages, and thus, cannot be reconstructed merely by comparing sounds among those daughter languages. * These phonemes, according to the most accepted variant of the theory, were laryngeal consonants of an indeterminate place of articulation towards the back of the mouth. The theory aims to: * Produce greater regularity in the reconstruction of PIE phonology than from the reconstruction that is produced by the comparative method. * Extend the general occurrence of the Indo-European ablaut to syllables with reconstructed vowel phonemes other than *e or *o. In its earlier form ( see below), the theory proposed two sounds in PIE ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Compensatory Lengthening

Compensatory lengthening in phonology and historical linguistics is the lengthening of a vowel sound that happens upon the loss of a following consonant, usually in the syllable coda, or of a vowel in an adjacent syllable. Lengthening triggered by consonant loss may be considered an extreme form of fusion (Crowley 1997:46). Both types may arise from speakers' attempts to preserve a word's moraic count. Examples English An example from the history of English is the lengthening of vowels that happened when the voiceless velar fricative and its palatal allophone were lost from the language. For example, in the Middle English of Chaucer's time the word ''night'' was phonemically ; later the was lost, but the was lengthened to to compensate, causing the word to be pronounced . (Later the became by the Great Vowel Shift.) Both the Germanic spirant law and the Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law show vowel lengthening compensating for the loss of a nasal. Non-rhotic forms of Englis ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Accusative

The accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to mark the direct object of a transitive verb. In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: 'me,' 'him,' 'her,' 'us,' and ‘them’. The spelling of those words will change depending on how they are used in a sentence. For example, the pronoun ''they'', as the subject of a sentence, is in the nominative case ("They wrote a book"); but if the pronoun is instead the object, it is in the accusative case and ''they'' becomes ''them'' ("The book was written by them"). The accusative case is used in many languages for the objects of (some or all) prepositions. It is usually combined with the nominative case (for example in Latin). The English term, "accusative", derives from the Latin , which, in turn, is a translation of the Greek . The word may also mean "causative", and this may have been the Greeks' intention in this name, but the sense of the Roman translation h ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Singular Number

In linguistics, grammatical number is a grammatical category of nouns, pronouns, adjectives and verb agreement that expresses count distinctions (such as "one", "two" or "three or more"). English and other languages present number categories of singular or plural, both of which are cited by using the hash sign (#) or by the numero signs "No." and "Nos." respectively. Some languages also have a dual, trial and paucal number or other arrangements. The count distinctions typically, but not always, correspond to the actual count of the referents of the marked noun or pronoun. The word "number" is also used in linguistics to describe the distinction between certain grammatical aspects that indicate the number of times an event occurs, such as the semelfactive aspect, the iterative aspect, etc. For that use of the term, see "Grammatical aspect". Overview Most languages of the world have formal means to express differences of number. One widespread distinction, found in English and ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Laryngeal Colouring

The laryngeal theory is a theory in the historical linguistics of the Indo-European languages positing that: * The Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) had a series of phonemes beyond those reconstructable by the comparative method. That is, the theory maintains that there were sounds in Proto-Indo-European that no longer exist in any of the daughter languages, and thus, cannot be reconstructed merely by comparing sounds among those daughter languages. * These phonemes, according to the most accepted variant of the theory, were laryngeal consonants of an indeterminate place of articulation towards the back of the mouth. The theory aims to: * Produce greater regularity in the reconstruction of PIE phonology than from the reconstruction that is produced by the comparative method. * Extend the general occurrence of the Indo-European ablaut to syllables with reconstructed vowel phonemes other than *e or *o. In its earlier form ( see below), the theory proposed two sounds in PIE. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Szemerényi's Law

Szemerényi's law (or Szemerényi's lengthening) is both a sound change and a synchronic phonological rule that operated during an early stage of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). Though its effects are evident in many reconstructed as well as attested forms, it did not operate in late PIE, having become morphologized (with exceptions reconstructible via the comparative method). It is named for Hungarian linguist Oswald Szemerényi. Overview The rule deleted coda fricatives *s or laryngeals *h₁, *h₂ or *h₃ (cover symbol *H), with compensatory lengthening occurring in a word-final position after resonants. In other words: : */-VRs/, */-VRH/ > *-VːR : */-VRH-/ > *-VR- (no examples of ''s''-deletion can be reconstructed for PIE) Morphological effects The law affected the nominative singular forms of the many masculine and feminine nouns whose stem ended in a resonant: * PIE "father" > (Ancient Greek '' patḗr'', Sanskrit '' pitā́'') * PIE "parent" > (Ancient ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sound Laws

A sound change, in historical linguistics, is a change in the pronunciation of a language. A sound change can involve the replacement of one speech sound (or, more generally, one phonetic feature value) by a different one (called phonetic change) or a more general change to the speech sounds that exist (phonological change), such as the merger of two sounds or the creation of a new sound. A sound change can eliminate the affected sound, or a new sound can be added. Sound changes can be environmentally conditioned if the change occurs in only some sound environments, and not others. The term "sound change" refers to diachronic changes, which occur in a language's sound system. On the other hand, " alternation" refers to changes that happen synchronically (within the language of an individual speaker, depending on the neighbouring sounds) and do not change the language's underlying system (for example, the ''-s'' in the English plural can be pronounced differently depending on ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |