|

Molecular Mimicry

Molecular mimicry is defined as the theoretical possibility that sequence similarities between foreign and self-peptides are sufficient to result in the cross-activation of autoreactive T or B cells by pathogen-derived peptides. Despite the prevalence of several peptide sequences which can be both foreign and self in nature, a single antibody or TCR (T cell receptor) can be activated by just a few crucial residues which stresses the importance of structural homology in the theory of molecular mimicry. Upon the activation of B or T cells, it is believed that these "peptide mimic" specific T or B cells can cross-react with self-epitopes, thus leading to tissue pathology (autoimmunity). Molecular mimicry is a phenomenon that has been just recently discovered as one of several ways in which autoimmunity can be evoked. A molecular mimicking event is, however, more than an epiphenomenon despite its low statistical probability of occurring and these events have serious implications in the o ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sequence Similarities

Sequence homology is the biological homology between DNA, RNA, or protein sequences, defined in terms of shared ancestry in the evolutionary history of life. Two segments of DNA can have shared ancestry because of three phenomena: either a speciation event (orthologs), or a duplication event (paralogs), or else a horizontal (or lateral) gene transfer event (xenologs). Homology among DNA, RNA, or proteins is typically inferred from their nucleotide or amino acid sequence similarity. Significant similarity is strong evidence that two sequences are related by evolutionary changes from a common ancestral sequence. Alignments of multiple sequences are used to indicate which regions of each sequence are homologous. Identity, similarity, and conservation The term "percent homology" is often used to mean "sequence similarity”, that is the percentage of identical residues (''percent identity''), or the percentage of residues conserved with similar physicochemical properties ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Apoptosis

Apoptosis (from grc, ἀπόπτωσις, apóptōsis, 'falling off') is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes ( morphology) and death. These changes include blebbing, cell shrinkage, nuclear fragmentation, chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, and mRNA decay. The average adult human loses between 50 and 70 billion cells each day due to apoptosis. For an average human child between eight and fourteen years old, approximately twenty to thirty billion cells die per day. In contrast to necrosis, which is a form of traumatic cell death that results from acute cellular injury, apoptosis is a highly regulated and controlled process that confers advantages during an organism's life cycle. For example, the separation of fingers and toes in a developing human embryo occurs because cells between the digits undergo apoptosis. Unlike necrosis, apoptosis produces cell fragments called apopt ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cytokines

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in autocrine, paracrine and endocrine signaling as immunomodulating agents. Cytokines include chemokines, interferons, interleukins, lymphokines, and tumour necrosis factors, but generally not hormones or growth factors (despite some overlap in the terminology). Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes and mast cells, as well as endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and various stromal cells; a given cytokine may be produced by more than one type of cell. They act through cell surface receptors and are especially important in the immune system; cytokines modulate the balance between humoral and cell-based immune responses, and they regulate the maturati ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Superantigen

Superantigens (SAgs) are a class of antigens that result in excessive activation of the immune system. Specifically it causes non-specific activation of T-cells resulting in polyclonal T cell activation and massive cytokine release. SAgs are produced by some pathogenic viruses and bacteria most likely as a defense mechanism against the immune system. Compared to a normal antigen-induced T-cell response where 0.0001-0.001% of the body's T-cells are activated, these SAgs are capable of activating up to 20% of the body's T-cells. Furthermore, Anti- CD3 and Anti-CD28 antibodies ( CD28-SuperMAB) have also shown to be highly potent superantigens (and can activate up to 100% of T cells). The large number of activated T-cells generates a massive immune response which is not specific to any particular epitope on the SAg thus undermining one of the fundamental strengths of the adaptive immune system, that is, its ability to target antigens with high specificity. More importantly, the l ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, responding to stimuli, providing structure to cells and organisms, and transporting molecules from one location to another. Proteins differ from one another primarily in their sequence of amino acids, which is dictated by the nucleotide sequence of their genes, and which usually results in protein folding into a specific 3D structure that determines its activity. A linear chain of amino acid residues is called a polypeptide. A protein contains at least one long polypeptide. Short polypeptides, containing less than 20–30 residues, are rarely considered to be proteins and are commonly called peptides. The individual amino acid residues are bonded together by peptide bonds and adjacent amino acid residues. The sequence of amino acid resid ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mitogen

A mitogen is a small bioactive protein or peptide that induces a cell to begin cell division, or enhances the rate of division (mitosis). Mitogenesis is the induction (triggering) of mitosis, typically via a mitogen. The mechanism of action of a mitogen is that it triggers signal transduction pathways involving mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), leading to mitosis. The cell cycle Mitogens act primarily by influencing a set of proteins which are involved in the restriction of progression through the cell cycle. The G1 checkpoint is controlled most directly by mitogens: further cell cycle progression does not need mitogens to continue. The point where mitogens are no longer needed to move the cell cycle forward is called the " restriction point" and depends on cyclins to be passed.Bohmer et al. "Cytoskeletal Integrity Is Required throughout the Mitogen Stimulation Phase of the Cell Cycle and Mediates the Anchorage-dependent Expression of Cyclin DI". January 1996, Molecular ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

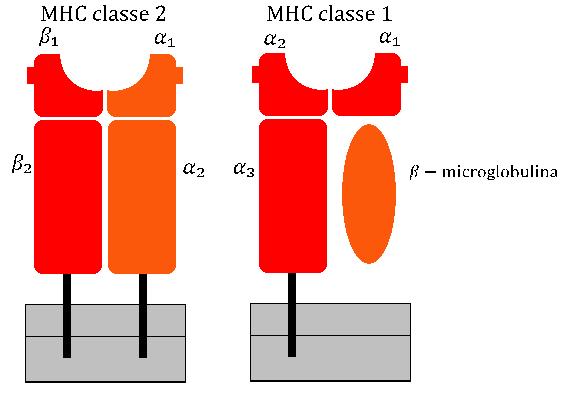

Major Histocompatibility Complex

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. These cell surface proteins are called MHC molecules. This locus got its name because it was discovered via the study of transplanted tissue compatibility. Later studies revealed that tissue rejection due to incompatibility is only a facet of the full function of MHC molecules: binding an antigen derived from self-proteins, or from pathogens, and bringing the antigen presentation to the cell surface for recognition by the appropriate T-cells. MHC molecules mediate the interactions of leukocytes, also called white blood cells (WBCs), with other leukocytes or with body cells. The MHC determines donor compatibility for organ transplant, as well as one's susceptibility to autoimmune diseases. In a cell, protein molecules of the host's own phenotype or of other biologic entit ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pathogenic

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ. The term ''pathogen'' came into use in the 1880s. Typically, the term ''pathogen'' is used to describe an ''infectious'' microorganism or agent, such as a virus, bacterium, protozoan, prion, viroid, or fungus. Small animals, such as helminths and insects, can also cause or transmit disease. However, these animals are usually referred to as parasites rather than pathogens. The scientific study of microscopic organisms, including microscopic pathogenic organisms, is called microbiology, while parasitology refers to the scientific study of parasites and the organisms that host them. There are several pathways through which pathogens can invade a host. The principal pathways have different episodic time frames, but soil has the longest ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Immunoglobulin

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the pathogen, called an antigen. Each tip of the "Y" of an antibody contains a paratope (analogous to a lock) that is specific for one particular epitope (analogous to a key) on an antigen, allowing these two structures to bind together with precision. Using this binding mechanism, an antibody can ''tag'' a microbe or an infected cell for attack by other parts of the immune system, or can neutralize it directly (for example, by blocking a part of a virus that is essential for its invasion). To allow the immune system to recognize millions of different antigens, the antigen-binding sites at both tips of the antibody come in an equally wide variety. In contrast, the remainder of the antibody is relatively constant. It only occurs in a few varian ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

V(D)J Recombination

V(D)J recombination is the mechanism of somatic recombination that occurs only in developing lymphocytes during the early stages of T and B cell maturation. It results in the highly diverse repertoire of antibodies/immunoglobulins and T cell receptors (TCRs) found in B cells and T cells, respectively. The process is a defining feature of the adaptive immune system. V(D)J recombination in mammals occurs in the primary lymphoid organs ( bone marrow for B cells and thymus for T cells) and in a nearly random fashion rearranges variable (V), joining (J), and in some cases, diversity (D) gene segments. The process ultimately results in novel amino acid sequences in the antigen-binding regions of immunoglobulins and TCRs that allow for the recognition of antigens from nearly all pathogens including bacteria, viruses, parasites, and worms as well as "altered self cells" as seen in cancer. The recognition can also be allergic in nature (''e.g.'' to pollen or other allergens) or m ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Klaus Rajewsky

Klaus Rajewsky (born 12 November 1936 in Frankfurt am Main) is a German immunologist, renowned for his work on B cells. He studied medicine in Frankfurt, Munich and at the Pasteur Institute, Paris. In 1964 he started working at the Institute of Genetics in the University of Cologne, where he became professor for genetics. He researched Hodgkin's disease and the role of B cells within the immune system. He also developed conditional knockout mice based on Cre-Lox recombination. He is one of the founding fathers of the German society for immunology (1967). Since 1994 he has been a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences. From 1995 to 2001 he was head of the Monterotondo station of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory near Rome. In 1996 he was awarded the Robert Koch Prize (shared with Fritz Melchers). In 1998 he founded Artemis Pharmaceuticals, together with Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and Peter Stadler. In 2001 he started working at the Cent ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Adjuvant

In pharmacology, an adjuvant is a drug or other substance, or a combination of substances, that is used to increase the efficacy or potency of certain drugs. Specifically, the term can refer to: * Adjuvant therapy Adjuvant therapy, also known as adjunct therapy, adjuvant care, or augmentation therapy, is a therapy that is given in addition to the primary or initial therapy to maximize its effectiveness. The surgeries and complex treatment regimens used i ... in cancer management * Analgesic adjuvant in pain management * Immunologic adjuvant in vaccines This is a specialized usage of a word (derived from the Latin verb "adjuvare", ''to help''), which also has a more general meaning as someone or something assisting in any operation or effect. {{sia Adjuvants ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |