|

Illicit Major

Illicit major is a formal fallacy committed in a categorical syllogism that is invalid because its major term is undistributed in the major premise but distributed in the conclusion. This fallacy has the following argument form: #''All A are B'' #''No C are A'' #''Therefore, no C are B'' Example: #''All dogs are mammals'' #''No cats are dogs'' #''Therefore, no cats are mammals'' In this argument, the major term is "mammals". This is distributed in the conclusion (the last statement) because we are making a claim about a property of ''all'' mammals: that they are not cats. However, it is not distributed in the major premise (the first statement) where we are only talking about a property of ''some'' mammals: Only some mammals are dogs. The error is in assuming that the converse of the first statement (that all mammals are dogs) is also true. However, an argument in the following form differs from the above, and is valid (Camestres): #''All A are B'' #''No B are C'' #''Therefore, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Formal Fallacy

In philosophy, a formal fallacy, deductive fallacy, logical fallacy or non sequitur (; Latin for " tdoes not follow") is a pattern of reasoning rendered invalid by a flaw in its logical structure that can neatly be expressed in a standard logic system, for example propositional logic.Harry J. Gensler, ''The A to Z of Logic'' (2010) p. 74. Rowman & Littlefield, It is defined as a deductive argument that is invalid. The argument itself could have true premises, but still have a false conclusion. Thus, a formal fallacy is a fallacy where deduction goes wrong, and is no longer a logical process. This may not affect the truth of the conclusion, since validity and truth are separate in formal logic. While a logical argument is a non sequitur if, and only if, it is invalid, the term "non sequitur" typically refers to those types of invalid arguments which do not constitute formal fallacies covered by particular terms (e.g., affirming the consequent). In other words, in practice, "''non s ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Categorical Syllogism

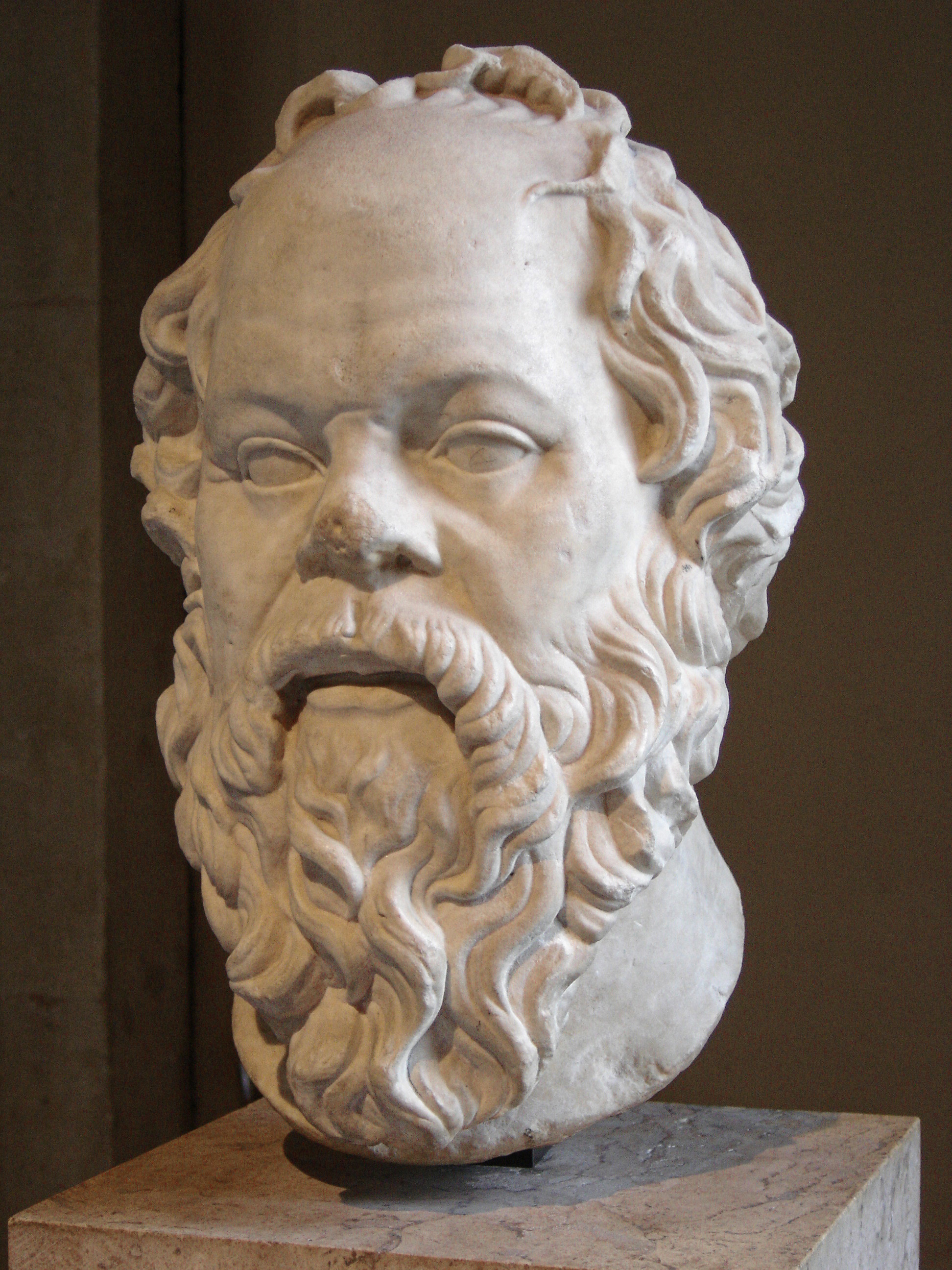

A syllogism ( grc-gre, συλλογισμός, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true. In its earliest form (defined by Aristotle in his 350 BCE book ''Prior Analytics''), a syllogism arises when two true premises (propositions or statements) validly imply a conclusion, or the main point that the argument aims to get across. For example, knowing that all men are mortal (major premise) and that Socrates is a man (minor premise), we may validly conclude that Socrates is mortal. Syllogistic arguments are usually represented in a three-line form: All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.In antiquity, two rival syllogistic theories existed: Aristotelian syllogism and Stoic syllogism. From the Middle Ages onwards, ''categorical syllogism'' and ''syllogism'' were usually used interchangeably. This ar ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Validity (logic)

In logic, specifically in deductive reasoning, an argument is valid if and only if it takes a form that makes it impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion nevertheless to be false. It is not required for a valid argument to have premises that are actually true, but to have premises that, if they were true, would guarantee the truth of the argument's conclusion. Valid arguments must be clearly expressed by means of sentences called well-formed formulas (also called ''wffs'' or simply ''formulas''). The validity of an argument can be tested, proved or disproved, and depends on its logical form. Arguments In logic, an argument is a set of statements expressing the ''premises'' (whatever consists of empirical evidences and axiomatic truths) and an ''evidence-based conclusion.'' An argument is ''valid'' if and only if it would be contradictory for the conclusion to be false if all of the premises are true. Validity doesn't require the truth of the premises, inst ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Major Term

A syllogism ( grc-gre, συλλογισμός, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true. In its earliest form (defined by Aristotle in his 350 BCE book '' Prior Analytics''), a syllogism arises when two true premises (propositions or statements) validly imply a conclusion, or the main point that the argument aims to get across. For example, knowing that all men are mortal (major premise) and that Socrates is a man (minor premise), we may validly conclude that Socrates is mortal. Syllogistic arguments are usually represented in a three-line form: All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.In antiquity, two rival syllogistic theories existed: Aristotelian syllogism and Stoic syllogism. From the Middle Ages onwards, ''categorical syllogism'' and ''syllogism'' were usually used interchangeably. This ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Distribution Of Terms

In logic, a categorical proposition, or categorical statement, is a proposition that asserts or denies that all or some of the members of one category (the ''subject term'') are included in another (the ''predicate term''). The study of arguments using categorical statements (i.e., syllogisms) forms an important branch of deductive reasoning that began with the Ancient Greeks. The Ancient Greeks such as Aristotle identified four primary distinct types of categorical proposition and gave them standard forms (now often called ''A'', ''E'', ''I'', and ''O''). If, abstractly, the subject category is named ''S'' and the predicate category is named ''P'', the four standard forms are: *All ''S'' are ''P''. (''A'' form, \forall _\rightarrow P_xequiv \forall neg S_\lor P_x/math>) *No ''S'' are ''P''. (''E'' form, \forall _\rightarrow \neg P_xequiv \forall neg S_\lor \neg P_x/math>) *Some ''S'' are ''P''. (''I'' form, \exists _\land P_x/math>) *Some ''S'' are not ''P''. (''O'' form, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Illicit Minor

Illicit minor is a formal fallacy committed in a categorical syllogism that is invalid because its minor term is undistributed in the minor premise but distributed in the conclusion. This fallacy has the following argument form: :All A are B. :All A are C. :Therefore, all C are B. ''Example:'' : All cats are felines. : All cats are mammals. : Therefore, all mammals are felines. The minor term here is mammal, which is not distributed in the minor premise "All cats are mammals", because this premise is only defining a property of possibly some mammals (i.e., that they're cats.) However, in the conclusion "All mammals are felines", mammal ''is'' distributed (it is talking about all mammals being felines). It is shown to be false by any mammal that is not a feline; for example, a dog. ''Example:'' : Pie is good. : Pie is unhealthy. : Thus, all good things are unhealthy. See also * Illicit major * Syllogistic fallacy A syllogism ( grc-gre, συλλογισμός, ''syl ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Syllogistic Fallacy

A syllogism ( grc-gre, συλλογισμός, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true. In its earliest form (defined by Aristotle in his 350 BCE book ''Prior Analytics''), a syllogism arises when two true premises (propositions or statements) validly imply a conclusion, or the main point that the argument aims to get across. For example, knowing that all men are mortal (major premise) and that Socrates is a man (minor premise), we may validly conclude that Socrates is mortal. Syllogistic arguments are usually represented in a three-line form: All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.In antiquity, two rival syllogistic theories existed: Aristotelian syllogism and Stoic syllogism. From the Middle Ages onwards, ''categorical syllogism'' and ''syllogism'' were usually used interchangeably. This ar ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |