|

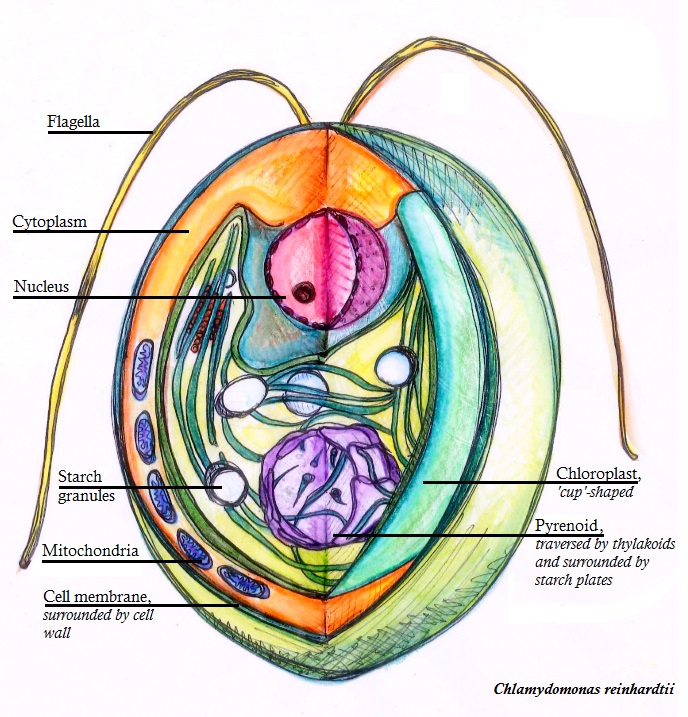

Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii

''Chlamydomonas reinhardtii'' is a single-cell green alga about 10 micrometres in diameter that swims with two flagella. It has a cell wall made of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins, a large cup-shaped chloroplast, a large pyrenoid, and an eyespot that senses light. '' Chlamydomonas'' species are widely distributed worldwide in soil and fresh water. ''Chlamydomonas reinhardtii'' is an especially well studied biological model organism, partly due to its ease of culturing and the ability to manipulate its genetics. When illuminated, ''C. reinhardtii'' can grow photoautotrophically, but it can also grow in the dark if supplied with organic carbon. Commercially, ''C. reinhardtii'' is of interest for producing biopharmaceuticals and biofuel, as well being a valuable research tool in making hydrogen. History The ''C. reinhardtii'' wild-type laboratory strain c137 (mt+) originates from an isolate collected near Amherst, Massachusetts, in 1945 by Gilbert M. Smith. The species' n ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pierre Clement Augustin Dangeard

Pierre Clement Augustin Dangeard (23 November 1862, Ségrie – 10 November 1947, Ségrie) was a botanist and mycologist known for his investigations of sexual reproduction in fungi. He was the father of botanist Pierre Dangeard (1895–1970) and geologist Louis Dangeard (1898–1987). Beginning in 1883, he worked as a ''préparateur'' to the faculty at Caen, earning his doctorate in 1886. Following graduation, he served as chief of ''travaux de botanique''. In 1891 he was appointed associate professor of botany at the University of Poitiers, later relocating to Paris as a lecturer at the faculty of sciences. In 1921 he attained the title of professor in Paris. In 1887 he founded the scientific journal ''Le Botaniste''. He was the member of several learned societies, such as the Académie des sciences (1917), the Société botanique de France (president 1914–18) and the Société mycologique de France. He was the circumscriber of the mycological genus ''Amoebophilus''. [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Molecular Biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physical structure of biological macromolecules is known as molecular biology. Molecular biology was first described as an approach focused on the underpinnings of biological phenomena - uncovering the structures of biological molecules as well as their interactions, and how these interactions explain observations of classical biology. In 1945 the term molecular biology was used by physicist William Astbury. In 1953 Francis Crick, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and colleagues, working at Medical Research Council unit, Cavendish laboratory, Cambridge (now the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology), made a double helix model of DNA which changed the entire research scenario. They proposed the DNA structure based on previous research done by Ro ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Isogamy

Isogamy is a form of sexual reproduction that involves gametes of the same morphology (indistinguishable in shape and size), found in most unicellular eukaryotes. Because both gametes look alike, they generally cannot be classified as male or female. Instead, organisms undergoing isogamy are said to have different mating types, most commonly noted as "+" and "−" strains. Etymology The literal meaning of isogamy is "equal marriage" which refers to equal contribution of resources by both gametes to a zygote. The term isogamous was first used in the year 1887. Characteristics of isogamous species Isogamous species often have two mating types. Some isogamous species have more than two mating types, but the number is usually lower than ten. In some extremely rare cases a species can have thousands of mating types. In all cases, fertilization occurs when gametes of two different mating types fuse to form a zygote. Evolution It is generally accepted that isogamy is an an ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mating Type

Mating types are the microorganism equivalent to sexes in multicellular lifeforms and are thought to be the ancestor to distinct Sex, sexes. They also occur in macro-organisms such as fungi. Definition Mating types are the microorganism equivalent to sex in higher organisms and occur in isogamy, isogamous and anisogamous species. Depending on the group, different mating types are often referred to by numbers, letters, or simply "+" and "−" instead of "male" and "female", which refer to "Sex, sexes" or differences in size between gametes. Syngamy can only take place between gametes carrying different mating types. Occurrence Reproduction by mating types is especially prevalent in Fungus, fungi. Filamentous ascomycetes usually have two mating types referred to as "MAT1-1" and "MAT1-2", following the yeast mating-type locus (MAT). Under standard nomenclature, MAT1-1 (which may informally be called MAT1) encodes for a regulatory protein with an alpha box motif, while MAT1-2 (informal ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at seventh in total abundance in the Milky Way and the Solar System. At standard temperature and pressure, two atoms of the element bond to form N2, a colorless and odorless diatomic gas. N2 forms about 78% of Earth's atmosphere, making it the most abundant uncombined element. Nitrogen occurs in all organisms, primarily in amino acids (and thus proteins), in the nucleic acids ( DNA and RNA) and in the energy transfer molecule adenosine triphosphate. The human body contains about 3% nitrogen by mass, the fourth most abundant element in the body after oxygen, carbon, and hydrogen. The nitrogen cycle describes the movement of the element from the air, into the biosphere and organic compounds, then back into the atmosphere. Many indus ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Chromosomes

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are the histones. These proteins, aided by chaperone proteins, bind to and condense the DNA molecule to maintain its integrity. These chromosomes display a complex three-dimensional structure, which plays a significant role in transcriptional regulation. Chromosomes are normally visible under a light microscope only during the metaphase of cell division (where all chromosomes are aligned in the center of the cell in their condensed form). Before this happens, each chromosome is duplicated (S phase), and both copies are joined by a centromere, resulting either in an X-shaped structure (pictured above), if the centromere is located equatorially, or a two-arm structure, if the centromere is located distally. The joined copies are now called sis ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively, in each homologous chromosome pair, which chromosomes naturally exist as. Somatic cells, tissues, and individual organisms can be described according to the number of sets of chromosomes present (the "ploidy level"): monoploid (1 set), diploid (2 sets), triploid (3 sets), tetraploid (4 sets), pentaploid (5 sets), hexaploid (6 sets), heptaploid or septaploid (7 sets), etc. The generic term polyploid is often used to describe cells with three or more chromosome sets. Virtually all sexually reproducing organisms are made up of somatic cells that are diploid or greater, but ploidy level may vary widely between different organisms, between different tissues within the same organism, and at different stages in an organism's life cycle. Half ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mitochondrion

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used throughout the cell as a source of chemical energy. They were discovered by Albert von Kölliker in 1857 in the voluntary muscles of insects. The term ''mitochondrion'' was coined by Carl Benda in 1898. The mitochondrion is popularly nicknamed the "powerhouse of the cell", a phrase coined by Philip Siekevitz in a 1957 article of the same name. Some cells in some multicellular organisms lack mitochondria (for example, mature mammalian red blood cells). A large number of unicellular organisms, such as microsporidia, parabasalids and diplomonads, have reduced or transformed their mitochondria into other structures. One eukaryote, ''Monocercomonoides'', is known to have completely lost its mitochondria, and one multicellular organism, '' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Optogenetics

Optogenetics is a biological technique to control the activity of neurons or other cell types with light. This is achieved by expression of light-sensitive ion channels, pumps or enzymes specifically in the target cells. On the level of individual cells, light-activated enzymes and transcription factors allow precise control of biochemical signaling pathways. In systems neuroscience, the ability to control the activity of a genetically defined set of neurons has been used to understand their contribution to decision making, learning, fear memory, mating, addiction, feeding, and locomotion. In a first medical application of optogenetic technology, vision was partially restored in a blind patient. Optogenetic techniques have also been introduced to map the functional connectivity of the brain''.'' By altering the activity of genetically labelled neurons with light and using imaging and electrophysiology techniques to record the activity of other cells, researchers can identify ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Light-gated Ion Channel

Light-gated ion channels are a family of ion channels regulated by electromagnetic radiation. Other gating mechanisms for ion channels include voltage-gated ion channels, ligand-gated ion channels, mechanosensitive ion channels, and temperature-gated ion channels. Most light-gated ion channels have been synthesized in the laboratory for study, although two naturally occurring examples, channelrhodopsin and anion-conducting channelrhodopsin, are currently known. Photoreceptor proteins, which act in a similar manner to light-gated ion channels, are generally classified instead as G protein-coupled receptors. Mechanism Light-gated ion channels function in a similar manner to other gated ion channels. Such transmembrane proteins form pores through lipid bilayers to facilitate the passage of ions. These ions move from one side of the membrane to another under the influence of an electrochemical gradient. When exposed to a stimulus, a conformational change occurs in the transmembrane ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, responding to stimuli, providing structure to cells and organisms, and transporting molecules from one location to another. Proteins differ from one another primarily in their sequence of amino acids, which is dictated by the nucleotide sequence of their genes, and which usually results in protein folding into a specific 3D structure that determines its activity. A linear chain of amino acid residues is called a polypeptide. A protein contains at least one long polypeptide. Short polypeptides, containing less than 20–30 residues, are rarely considered to be proteins and are commonly called peptides. The individual amino acid residues are bonded together by peptide bonds and adjacent amino acid residues. The sequence of amino acid residue ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Channelrhodopsin

Channelrhodopsins are a subfamily of retinylidene proteins ( rhodopsins) that function as light-gated ion channels. They serve as sensory photoreceptors in unicellular green algae, controlling phototaxis: movement in response to light. Expressed in cells of other organisms, they enable light to control electrical excitability, intracellular acidity, calcium influx, and other cellular processes (see optogenetics). Channelrhodopsin-1 (ChR1) and Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) from the model organism ''Chlamydomonas reinhardtii'' are the first discovered channelrhodopsins. Variants that are sensitive to different colors of light or selective for specific ions (ACRs, KCRs) have been cloned from other species of algae and protists. History Phototaxis and photoorientation of microalgae have been studied over more than hundred years in many laboratories worldwide. In 1980, Ken Foster developed the first consistent theory about the functionality of algal eyes. He also analyzed published ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |