|

Aryldialkylphosphatase

Aryldialkylphosphatase (EC 3.1.8.1, also known as phosphotriesterase, organophosphate hydrolase, parathion hydrolase, paraoxonase, and parathion aryl esterase; systematic name aryltriphosphate dialkylphosphohydrolase) is a metalloenzyme that hydrolyzes the triester linkage found in organophosphate insecticides: :an aryl dialkyl phosphate + H2O \rightleftharpoons dialkyl phosphate + an aryl alcohol The gene (''opd'', for organophosphate-degrading) that codes for the enzyme is found in a large plasmid (pSC1, 51Kb) endogenous to ''Pseudomonas'' ''diminuta'', although the gene has also been found in many other bacterial species such as ''Flavobacterium'' sp. (ATCC27551), where it is also encoded in an extrachromosomal element (pSM55, 43Kb). Organophosphate is the general name for esters of phosphoric acid and is one of the organophosphorus compounds. They can be found as part of insecticides, herbicides, and nerve gases, amongst others. Some less-toxic organophosphates can be ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Parathion

Parathion, also called parathion-ethyl or diethyl parathion and locally known as "Folidol", is an organophosphate insecticide and acaricide. It was originally developed by IG Farben in the 1940s. It is highly toxic to non-target organisms, including humans, so its use has been banned or restricted in most countries. The basic structure is shared by parathion methyl. History Parathion was developed by Gerhard Schrader for the German trust IG Farben in the 1940s. After World War II and the collapse of IG Farben due to the war crime trials, the Western allies seized the patent, and parathion was marketed worldwide by different companies and under different brand names. The most common German brand was E605 (banned in Germany after 2002); this was not a food-additive "E number" as used in the EU today. "E" stands for ''Entwicklungsnummer'' (German for "development number"). It is an irreversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. Safety concerns have later led to the development o ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

EP Additives

Extreme pressure additives, or EP additives, are additives for lubricants with a role to decrease wear of the parts of the gears exposed to very high pressures. They are also added to cutting fluids for machining of metals. Extreme pressure additives are usually used in applications such as gearboxes, while antiwear additives are used with lighter load applications such as hydraulic and automotive engines. Extreme pressure gear oils perform well over a range of temperatures, speeds and gear sizes to help prevent damage to the gears during starting and stopping of the engine. Unlike antiwear additives, extreme pressure additives are rarely used in motor oils. The sulfur or chlorine compounds contained in them can react with water and combustion byproducts, forming acids that facilitate corrosion of the engine parts and bearings. Extreme pressure additives typically contain organic sulfur, phosphorus or chlorine compounds, including sulfur-phosphorus and sulfur-phosphorus-boron comp ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Upstream And Downstream (DNA)

In molecular biology and genetics, upstream and downstream both refer to relative positions of genetic code in DNA or RNA. Each strand of DNA or RNA has a 5' end and a 3' end, so named for the carbon position on the deoxyribose (or ribose) ring. By convention, upstream and downstream relate to the 5' to 3' direction respectively in which RNA transcription takes place. Upstream is toward the 5' end of the RNA molecule and downstream is toward the 3' end. When considering double-stranded DNA, upstream is toward the 5' end of the coding strand for the gene in question and downstream is toward the 3' end. Due to the anti-parallel nature of DNA, this means the 3' end of the template strand is upstream of the gene and the 5' end is downstream. Some genes on the same DNA molecule may be transcribed in opposite directions. This means the upstream and downstream areas of the molecule may change depending on which gene is used as the reference. See also *Upstream and downstream (transdu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Transposase

A transposase is any of a class of enzymes capable of binding to the end of a transposon and catalysing its movement to another part of a genome, typically by a cut-and-paste mechanism or a replicative mechanism, in a process known as transposition. The word "transposase" was first coined by the individuals who cloned the enzyme required for transposition of the Tn3 transposon. The existence of transposons was postulated in the late 1940s by Barbara McClintock, who was studying the inheritance of maize, but the actual molecular basis for transposition was described by later groups. McClintock discovered that some segments of chromosomes changed their position, jumping between different loci or from one chromosome to another. The repositioning of these transposons (which coded for color) allowed other genes for pigment to be expressed. Transposition in maize causes changes in color; however, in other organisms, such as bacteria, it can cause antibiotic resistance. Transposition is als ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tn3 Transposon

The Tn3 transposon is a 4957 base pair mobile genetic element, found in prokaryotes. It encodes three proteins: * β-lactamase, an enzyme that confers resistance to β-lactam antibiotics (and is encoded by the gene Bla). * Tn3 transposase (encoded by gene tnpA) * Tn3 resolvase (encoded by gene tnpR) Initially discovered as a repressor of transposase, resolvase also plays a role in facilitating Tn3 replication (Sherratt 1989). The transposon is flanked by a pair of 38bp inverted repeats. Mechanism of replication Step 1 – Replicative integration This first stage is catalysed by transposase. The plasmid containing the transposon (the donor plasmid) fuses with a host plasmid (the target plasmid). In the process, the transposon and a short section of host DNA are replicated. The end product is a 'cointegrate' plasmid containing two copies of the transposon. Shapiro (1978) proposed the following mechanism for this process: # Four single-strand cleavages occur – one on each s ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Transposable Element

A transposable element (TE, transposon, or jumping gene) is a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome, sometimes creating or reversing mutations and altering the cell's genetic identity and genome size. Transposition often results in duplication of the same genetic material. Barbara McClintock's discovery of them earned her a Nobel Prize in 1983. Its importance in personalized medicine is becoming increasingly relevant, as well as gaining more attention in data analytics given the difficulty of analysis in very high dimensional spaces. Transposable elements make up a large fraction of the genome and are responsible for much of the mass of DNA in a eukaryotic cell. Although TEs are selfish genetic elements, many are important in genome function and evolution. Transposons are also very useful to researchers as a means to alter DNA inside a living organism. There are at least two classes of TEs: Class I TEs or retrotransposons generally functi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Conserved Sequence

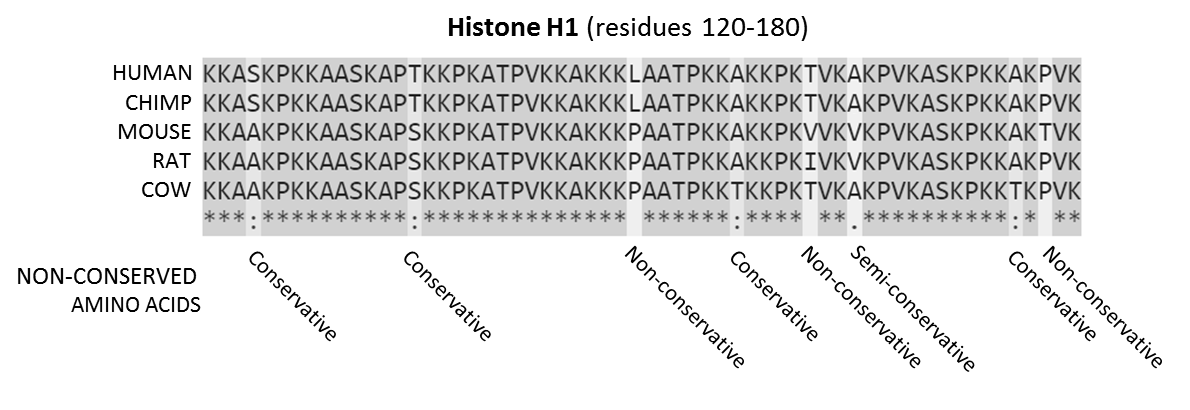

In evolutionary biology, conserved sequences are identical or similar sequences in nucleic acids ( DNA and RNA) or proteins across species ( orthologous sequences), or within a genome ( paralogous sequences), or between donor and receptor taxa ( xenologous sequences). Conservation indicates that a sequence has been maintained by natural selection. A highly conserved sequence is one that has remained relatively unchanged far back up the phylogenetic tree, and hence far back in geological time. Examples of highly conserved sequences include the RNA components of ribosomes present in all domains of life, the homeobox sequences widespread amongst Eukaryotes, and the tmRNA in Bacteria. The study of sequence conservation overlaps with the fields of genomics, proteomics, evolutionary biology, phylogenetics, bioinformatics and mathematics. History The discovery of the role of DNA in heredity, and observations by Frederick Sanger of variation between animal insulins in 1949, prompt ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sequence Homology

Sequence homology is the biological homology between DNA, RNA, or protein sequences, defined in terms of shared ancestry in the evolutionary history of life. Two segments of DNA can have shared ancestry because of three phenomena: either a speciation event (orthologs), or a duplication event (paralogs), or else a horizontal (or lateral) gene transfer event (xenologs). Homology among DNA, RNA, or proteins is typically inferred from their nucleotide or amino acid sequence similarity. Significant similarity is strong evidence that two sequences are related by evolutionary changes from a common ancestral sequence. Alignments of multiple sequences are used to indicate which regions of each sequence are homologous. Identity, similarity, and conservation The term "percent homology" is often used to mean "sequence similarity”, that is the percentage of identical residues (''percent identity''), or the percentage of residues conserved with similar physicochemical properties (' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb) is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis. First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' has an unusual, waxy coating on its cell surface primarily due to the presence of mycolic acid. This coating makes the cells impervious to Gram staining, and as a result, ''M. tuberculosis'' can appear weakly Gram-positive. Acid-fastness, Acid-fast stains such as Ziehl–Neelsen stain, Ziehl–Neelsen, or Fluorescence, fluorescent stains such as Auramine O, auramine are used instead to identify ''M. tuberculosis'' with a microscope. The physiology of ''M. tuberculosis'' is highly aerobic organism, aerobic and requires high levels of oxygen. Primarily a pathogen of the mammalian respiratory system, it infects the lungs. The most frequently used diagnostic methods for tuberculosis are the Mantoux test, tuberculin skin test, Acid-Fast Stain, acid-fast stain, Microbiological cultu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Escherichia Coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escherichia'' that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms. Most ''E. coli'' strains are harmless, but some serotypes ( EPEC, ETEC etc.) can cause serious food poisoning in their hosts, and are occasionally responsible for food contamination incidents that prompt product recalls. Most strains do not cause disease in humans and are part of the normal microbiota of the gut; such strains are harmless or even beneficial to humans (although these strains tend to be less studied than the pathogenic ones). For example, some strains of ''E. coli'' benefit their hosts by producing vitamin K2 or by preventing the colonization of the intestine by pathogenic bacteria. These mutually beneficial relationships between ''E. col ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Alteromonas

''Alteromonas'' is a genus of Pseudomonadota found in sea water, either in the open ocean or in the coast. It is Gram-negative. Its cells are curved rods with a single polar flagellum. Etymology The etymology of the genus is Latin ''alter'' -''tera'' -''terum'', another, different; ''monas'' (μονάς), a noun with a special meaning in microbiology used to mean unicellular organism; to give ''Alteromonas'', another monad Members of the genus ''Alteromonas'' can be referred to as alteromonads (''viz.'' Trivialisation of names). Authority The genus was described by Baumann ''et al.'' in 1972, but was emended by Novick and Tyler 1985 to accommodate ''Alteromonas luteoviolacea'' (now ''Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea''), Gauthier et al. 1995, who split the genus in two (''Pseudoalteromonas'') and Van Trappen et al. in 2004 to accommodate ''Alteromonas stellipolaris''. Species The genus contains eight species (but 21 basonyms), namely * '' A. addita'' (Ivanova ''et al''. 2005, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |